“They walked past red barns and white picket fences, past new housing developments and plowed fields dusted with snow. They walked with blisters on their feet and with hats pulled low to ward off the winter wind. They walked to remember.

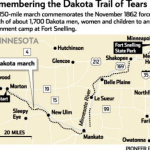

The sixth annual Dakota Commemorative Walk ends Tuesday, Nov. 13, 2012 after six days retracing the footsteps of the 1,700 Dakota women and children who were forced to march 150 miles to Fort Snelling after the U.S. Dakota War of 1862.

Some call it Minnesota’s Trail of Tears.

“This is a ceremony,” said Gwen Westerman, who teaches humanities at Minnesota State Mankato and who has walked with the group since 2004. “It’s not a protest. It’s not a re-enactment. It’s a spiritual ceremony for healing and for honoring those women and children we descend from. We remember their strength and their determination.”

The first commemorative walk was organized in 2002, and organizers have held one every two years, leading up to this year, the 150th anniversary of the original march. After the Dakota War of 1862, the Dakota men who attacked government offices and white settlements were given cursory trials. Just more than 303 were condemned, and 38 were hanged in Mankato, remembered as a notorious event in Minnesota history.

After the war, 1,700 men, women, children, elders and mixed-race noncombatants were marched to a fenced camp along the river beneath Fort Snelling. During the winter of 1862-63 hundreds died of illness and exposure. In the spring, the remaining 1,300 were taken by steamboat and trains to a semiarid reservation at Crow Creek, S.D., where many more died of starvation and illness.

“They lived through three horrific experiences,” said Chris Mato Nunpa, a retired professor at Southwest Minnesota State University, who was bundled in a black coat and who talked as he walked along the shoulder of the road.

“They lived through this forced march, through the concentration camp, and through the forcible removal from Minnesota.”

He called their ordeal a genocide.

This year’s walkers set out just after dawn Wednesday from the parking lot of the Lower Sioux Agency in Morton, in the Minnesota River Valley. By Monday afternoon, the group had passed through the town of Jordan after covering about 20 miles a day. They walked on the shoulder of Scott County Hwy. 17, followed by a caravan of cars and vans carrying friends, supporters and elders too frail to make the journey on foot. Some people walk all six days; others join for a few days or even a few hours.

Each day, the procession is led by a woman carrying a sacred pipe wrapped in a blanket, surrounded by a quiet group. Farther back, people chat. The walkers stop and place a marker about every mile and honor two ancestors from the march.

At one stop Monday, a woman cleared weeds growing at the base of a tall electrical pole. She pounded a stake into the ground, topped with red and yellow ribbons. Someone called the names on the ribbon into the chilly wind: “Alek Graham. Maline Mumford.”

Then one by one, people went forward, took a pinch of tobacco from a leather pouch and sprinkled it over the stake.

“The name is not just a name. When we call their name, they come,” explained Nick Anderson, cultural chairperson for the Mendota Mdewakanton Dakota Community. “They are here with us.”

He said he walked as a way to thank his ancestors, one of whom was a sister of Chief Little Crow.

“When I think of what they had to endure, I don’t know if we can ever give enough thanks,” he said. “We survived, but we have lost a lot of our culture. Participating in this is a way for me to get some of that back.”

Other people came long distances to walk.

“The reason I’m here is because my great grandmother was on this march with her four kids and her mother,” said Reuben Kitto, who flew in for the march from Florida, where he spent 30 years working for Honeywell. Kitto spent his childhood on the Santee Sioux Reservation in Nebraska where many Minnesota Dakota were sent.

“This walk brings us back to the reality of how hard it was for them,” Kitto said. “The weather was a lot like this, there was a little bit of snow.”

“It’s a way for me to spend a day with my grandmother,” he said.

It’s also a way for him to spend time with his living family. His nephew Robert Thomas drove up from Winona to join the march for a day. Thomas is working on a commissioned play about the Dakota war and exile for the Minnesota History Theater and is concerned with helping both Dakota and non-Dakota remember the Dakota’s past.

“The old aunties and uncles are still passing down the stories,” he said. “The struggle is to get the younger generation interested.”

Kitto’s daughter, Ramona Kitto Stately of Shakopee, also was on the march, bundled in a long red coat and walking next to her father. Stately coordinates Indian education for the Osseo Area Schools and this year, as in past years, brought several students along on the walk.

As the sun started to dip low, she and others arrived at the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community center, where they would eat dinner together and reflect on that day’s walk.

“We carry a deep grief inside and if we don’t connect with that grief, we can’t heal,” Stately said.” [credit]