“C.L.U.E. (color location ultimate experience) is a collaborative video, installation and performance work by artists A.L. Steiner + robbinschilds, with AJ Blandford and Seattle-based band Kinski. The performance and installation-based works have been presented in exhibition and performance venues internationally. The video works range from a single-channel piece (C.L.U.E., Part I), to multichannel pieces, up to 13-channels. ” (credit)

Category Archives: choreography

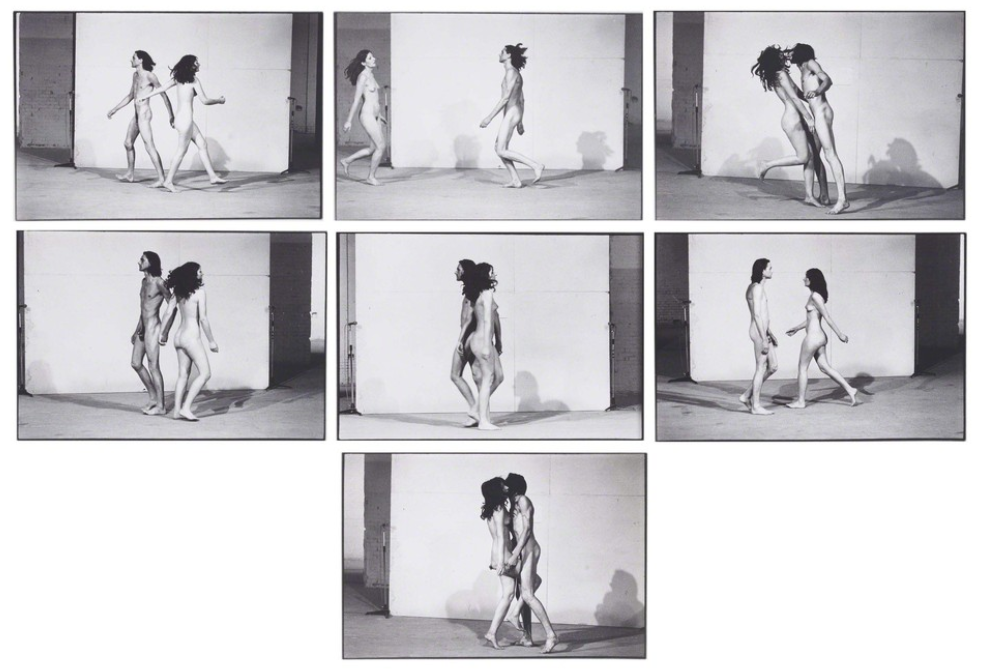

Marina Abramović and Ulay, Relation in Space (1976)

Diane Borsato, Touching 1000 People (2001-2003)

”

Diane Borsato, Your Temper, My Weather (2013)

“One hundred amateur and professional beekeepers performed periods of guided meditation and slow walking together in the Art Gallery of Ontario’s Walker Court. While exploring the tangible effect of collective stillness, the work created a platform upon which to

reflect on the health and temper of bees and their keepers, and on the policies and environmental conditions that affect our shared future. The work was performed for five hours for Nuit Blanche at the Art Gallery of Ontario.”

Credit: Morrell, Amish and Diane Borsato. Outdoor School: Contemporary Environmental Art. Douglas and McINtyre, 2021. Page 134.

- Nuit Blanche 2013 Diane Borsato: Your Temper, My Weather, 2013

- Nuit Blanche 2013 Diane Borsato: Your Temper, My Weather, 2013

- Nuit Blanche 2013 Diane Borsato: Your Temper, My Weather, 2013

Hélio Oiticica, Paranglolés (1964-1980)

“Oiticica’s most iconic artworks: parangolés, or wearable, experiential garments that he initiated in 1964 and continued working with for the rest of his career. Parangolés are capes, or cloak-like layers of different materials that were intended to be worn by moving and dancing participants. They were made of colored and painted fabrics, as well as nylon, burlap, and gauze. Some contained political or poetic texts, photographs, or painted images, along with bags of pebbles, sand, straw, or shells. They also sometimes took the form of flags, banners, or tents.

It was through learning to dance the samba that Oiticica developed the parangolé. He said that dancing freed him from art’s “excessive intellectualization.”[1] He learned about samba through his contact with the community of Mangueira, a favela (Brazilian slum) located on the outskirts of his hometown of Rio de Janeiro. He began visiting the favela in an attempt to escape what he perceived as the constraints of Rio de Janeiro’s art scene. Oiticica was white, middle class, and educated, while the favela’s inhabitants were mainly Black, poor, and uneducated. Despite the significance of this disparity, Oiticica developed friendships with a number of residents and was eventually accepted by the community. He learned to samba and even became a passista (a highly skilled dancer who performs in Brazilian Carnival) in the Mangueira samba school (a club for dancing and playing samba in the annual Carnival parade).

Oiticica asserted that the favela made him more aware of social inequities. As a result, the concept of “marginalization” became fundamental to him, especially as a gay man. He began to associate the marginalized position of the artist in society with the marginalization of favela communities. This was thrown into sharp relief when Oiticica invited some friends from Mangueira to help him inaugurate the parangolés by dancing in them in their first public presentation at the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro for the opening of the exhibition Opinião 65 (Opinion 65). The dancers were refused entry into the building, revealing the institutionalized racism and classism pervading Rio de Janeiro at the time. Even the word “parangolé” (meaning a sudden agitation, an unexpected situation, or a dance party) was rooted in marginalization: he adopted the term when he saw a piece of cloth with the word on it hung by a beggar on the street. Oiticica’s experience of the marginality of Rio de Janeiro’s most impoverished inhabitants awakened him to the social and ethical implications of art.

…

From participatory art to political resistance

The same year that Oiticica developed the parangolé, the Brazilian military (with U.S. support) launched a coup d’etat, initiating a twenty-one year military dictatorship. It was against the backdrop of increasing political repression that Oiticica began engaging the spectator as a participant in his works, an approach known today as participatory art. This approach to art engages the audience in the creative process so that they become collaborators in the work. A common interpretation of the parangolés is that they were intended to liberate their wearers from the repressive military regime by enabling them to become aware of their capacity to rebel.

Some parangolés even included political statements such as “Of Adversity We Live” (1965) or “I Embody Revolt” (1967). Such statements went unobserved by authorities because state-sponsored censorship initially focused more on the press and pop music than on visual art. More widespread censorship gained momentum only after 1968, when the dictatorship enacted the Institutional Act Number 5, leading to the imprisonment and torture of dissidents. Many artists, including Oiticica, left Brazil due to the increasing oppression. He travelled to London to mount his solo exhibition The Whitechapel Experiment at Whitechapel Gallery in 1969.

Parangolés in New York and beyond

Oiticica came to New York in 1970 to participate in Information, a group exhibition of conceptual art at The Museum of Modern Art. After winning a Guggenheim Fellowship the same year, he stayed in exile in the city for the next eight years. In 1973, he organized an excursion with some friends into the subway system in order to invite riders to try out the parangolés.[3] The interactive encounter represented a continuation of his exploration of the intersections of art and life and his interest in engaging non-art audiences. Much like the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, in the 1970s New York’s heavily-graffitied subway had the reputation of being a site of criminal activity, its denizens thought to be beggars, drug addicts, and gang members. Bringing the parangolé into that space attested to Oiticica’s continued socio-political commitment to engaging marginalized people through liberating experiences. He would continue to play and experiment with his parangolés until his untimely death in Rio de Janeiro in 1980 at the age of forty-two.

Parangolés demand to be worn and moved in, not observed as lifeless objects hung on a wall for display. Today, they are usually only seen in documentary photographs and films, rather than worn by the spectator. When samples are available to try on in exhibitions, they rarely match the lively energy they once inspired. Even so, they continue to have a lasting impact on participatory and socially engaged art practices.

Notes:

[1] Hélio Oiticica, “A Dança na minha experiência,” November 12, 1965, in Renato Rodrigues da Silva, “Hélio Oiticica’s Parangolé or the Art of Transgression,” Third Text vol. 19, no. 3 (2005): p. 214.

[3] Despite image captions that indicate the subway excursion occurred in 1972, the Projeto Hélio Oiticica affirms it took place in February 1973. See “Biography,” Projeto Hélio Oiticica.” (credit)

Lygia Pape, Divisor (Divider) (1968)

Lygia Pape, Divisor from Para Site on Vimeo.

Lygia Pape (1927-2004, Brazil)

“ was part of the generation of artists who founded the Neo–concrete movement in Brazil, an experimental moment of constructivism and geometric abstract art, which manifested in South America in the late 1950’s. Neoconcretist artists like Pape sought to explore ideas of colour and form in relation to the sensorial cartography of the individual and the collective.

The work Divisor was originally performed on the streets of Rio de Janeiro in 1968. It is composed of an immense white fabric, which can be seen as a large scale white monochrome and is activated by a participative audience. The only visible part of each participant is their head, piercing through the fabric, whilst their hidden bodies jointly move along public space. The amorphous mutant forms created throughout the piece reflect the subjectivity of the participants who struggle between individualism and solidarity with the collective experience.” (credit)

- Lygia Pape, Divisor

- Lygia Pape, Divisor

Mowry Baden, Seat Belt, Three Points (1970)

“Baden’s pieces forced viewers into awkward situations that expressed his interest in kinesthetics — physical perceptions and the changes that took place in neuromuscular memory as the body moved through the work. In Seat Belts (1969-71) Baden explored the difference between what it felt like to walk around a modified circle while tied with a strap from the waist to the floor and what it looked like it would feel like. He wanted to manipulate the “body prints” of the viewers to alter their perceptions of balance, and creating a new “sensory imprint” was his sculptural aspiration. … Baden’s experiments with sculptural-psychological, body-oriented works in the late 1960s and early 1970s would prove to be highly influential on artists such as Charles Ray and Chris Burden, both of whom were his students.” (Schimmel, Paul. “Leap into the Void: Performance and the Object,” Out of Actions: Between Performance and the Object, 1949-1979. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 1998. Page 94.)

- Installation view of Mowry Baden, exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery, March 9 to June 9, 2019

- Installation view of Mowry Baden, exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery, March 9 to June 9, 2019

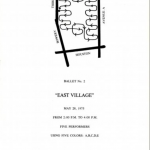

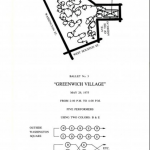

Daniel Buren, Seven Ballets in Manhattan” (1975)

Seven Ballets in Manhattan. Performed by Sue Bailey, Joanne Caring, Peter Frank, Susan Heinemann, Mark Levine. Choreography by Daniel Buren. May 27 – June 2, 1975.

Daniel Buren (1938-)

—

“The artist Daniel Buren explored the idea of movement through performance, it is no longer a question of static works but of an orchestrated choreography. It is in the form of an ambulatory ballet in the streets of New York, that he manages to put his emblematic motifs into action.

Indeed, for 5 days, 5 actors marched in different areas of the city, each of them carrying a poster covered with white and colored bands. In the manner of protesters, the performers walked according to the precise directives of the artist. They had to follow the imposed route and only respond to passers-by by the name of the color present on their respective poster. What could be described not as a peaceful demonstration, but rather as an artistic demonstration, comes to be placed as a questioning of the public. In fact, spectators no longer travel to museums or galleries, but the work comes directly to them.

This performance was not perceived in the same way on the different courses. Indeed, in each district evolved distinct socio-professional categories, the population of Soho was very curious and sensitive to the work, while the residents of Wall Street interpreted it as a threat in the image of a real demonstration.

Thus the performance, which is not a very common mode of presentation with Daniel Buren, creates a real tension with the public. It contrasts with the static aspect of its striped pattern, but manages through the use of posters to dialogue with the spectators and the city.” (credit)

Jeremy Deller, Battle of Orgreave (2001)

- The battlefield on the day before the performance.

- Participating former miners and their families on the day of the performance.

- Police officers pursuing miners through the village.

“In 1998 I saw an advert for an open commission for Artangel. For years I had had this idea to re-enact this confrontation that I had witnessed as a young person on TV, of striking miners being chased up a hill and pursued through a village. It has since become an iconic image of the 1984 strike – having the quality of a war scene rather than a labour dispute. I received the commission, which I couldn’t believe, because I actually didn’t think it was possible to do this. After two years’ research, the re-enactment finally happened, with about eight-hundred historical re-enactors and two-hundred former miners who had been part of the original conflict. Basically, I was asking the re-enactors to participate in the staging of a battle that occurred within living memory, alongside veterans of the campaign. I’ve always described it as digging up a corpse and giving it a proper post-mortem, or as a thousand-person crime re-enactment.” (credit)

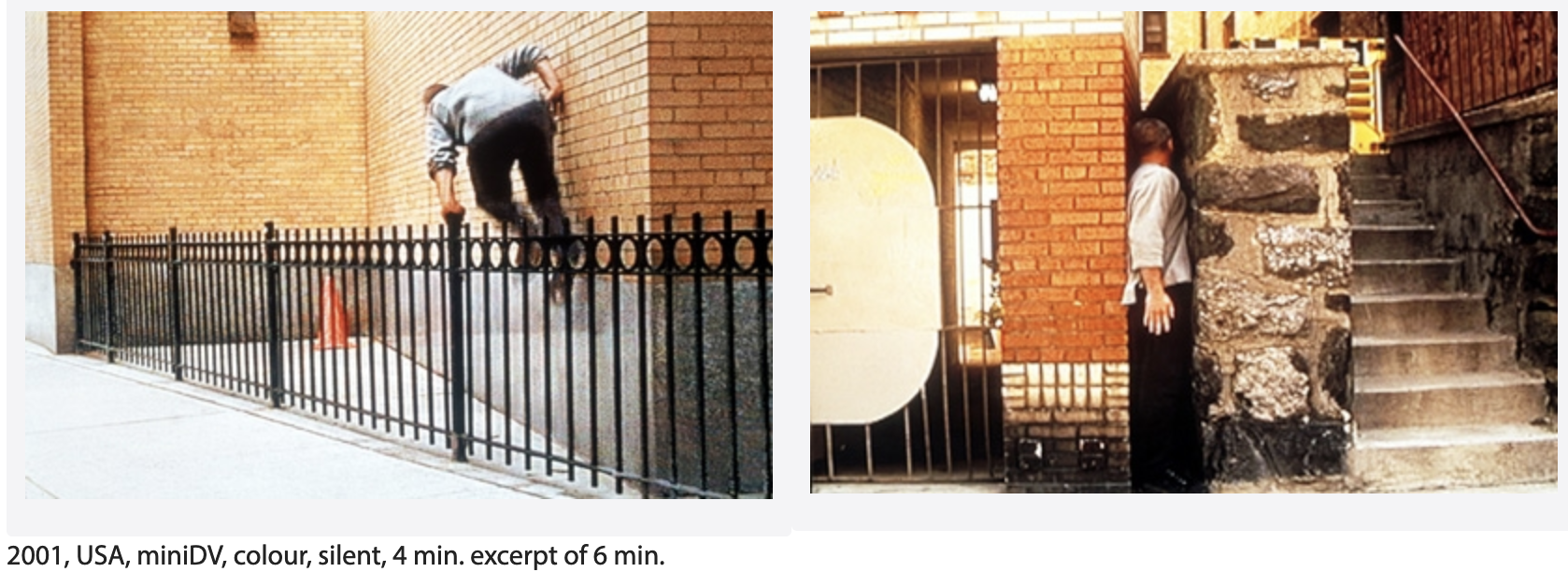

Alex Villar, Temporary Occupations (2001)

Alex Villar, Temporary Occupations, 2001, USA, miniDV, colour, silent, 4 min. excerpt of 6 min.

“Drawing from interdisciplinary theoretical sources and employing video-performance, installation and photography, I have developed a practice that concentrates on matters of social space. My interventions are done primarily in public spaces. They consist in positioning the body of the performer in situations where the codes that regulate everyday activity can be made explicit. The body is made to conform to the limitations of claustrophobic spaces, therefore accentuating arbitrary boundaries and possibly subverting them. A sense of absurdity permeates the work, counterpoising irrational behaviour to the instrumental logic of the city’s design.

Theoretical references cover the extensive work done on the problematic of space, especially the works of Foucault and de Certeau, which describe panopticon and heterotopic spaces as well as the potentialities for everyday re-writings of urban space. Aesthetic traditions foregrounding my work go from the sixties and seventies performative-based sculpture and installations by Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Clark and Cildo Meirelles, to the urban strategies of the Situationists and the anarchitecture of Gordon Matta-Clark. Like the in-between activities it seeks to investigate, my work lives between various fields: part nomadic architecture, part intangible sculpture and part performance without spectacle.

Temporary Occupations from alex villar on Vimeo.

Temporary Occupations depicts a person running on the sidewalk in New York while ignoring the city’s spatial codes and therefore resisting their effects upon the organization of everyday experience. The clips in the video register situations of temporary invasion and occupation of private spaces located in a public setting. The action simply articulates the continuity of these spaces with the remaining areas from which they were extricated, drawing attention to, and possibly subverting, the boundaries that demarcate them.

This piece is part of a long-term investigation and articulation of potential spaces of dissent in the urban landscape, which has often taken the form of an exploration of negative spaces in architecture.” (credit)