“Judy Marsh’s paintings use the visual language of the structures that shape our movement in the urban environment, particularly of hazard signs and barriers. In these sculptural paintings strips of black and white diagonal stripes protrude forwards with an arresting vibrancy. Left open at the side, the works invite the viewer to peer between the panels – filled with carefully executed scaffolding, these sections speak to the in-between spaces that emerge when two barriers are erected.” (credit)

Category Archives: Sculpture

Bill Gilbert, Walk to Work (2009)

“For twenty-two years I have made the hour long drive from my house in Cerrillos to my office at the University of New Mexico. For this piece, I decided to walk to work. I strapped on a backpack, headed out my door and walked as straight a line as possible (given the variations in topography, land ownership, etc.) to my office at UNM. Along the roughly 50 mile trek across ranch land, the Sandia Mountains and the northeast quadrant of Albuquerque I recorded my perceptions from the perspective of a lone hiker walking across the land.

This work is part of a series of “Physiocartographies.” Started in 2003 in the field with the Land Arts of the American West mobile studio, the physiocartographies series combines the abstraction of cartographic maps with the physical act of walking the surface of the planet to create portraits of place. In the various works from this series I follow prescribed paths across the landscape using a gps unit to navigate and record points, a camera to shoot images and a digital recorder to capture sounds. The final works appear as reconstructed maps, videos and installations.” (credit)

Beverly Buchanan, Marsh Ruins (1981)

Beverly Buchanan (1940-2015)

“This text originally appeared in ART PAPERS Fall/Winter 2020, Monumental Interventions, as part of a special dossier highlighting seven artists who have fought—and continue the fight—to transform their public spaces by uncovering suppressed histories, resisting oppression, and telling formerly silenced truths.

Beverly Buchanan’s practice referenced southern vernacular architecture to interrogate relationships between Black people, history, and the landscape. In 1981 Buchanan (1940–2015) placed a triangular formation of three sculptural mounds on the edge of the tidal marsh in Brunswick, GA. Titled Marsh Ruins, the large amorphous forms were made by layering concrete and tabby—a concrete made from lime, water, sand, oyster shells, and ash—and then staining the forms brown. This grouping is the most referenced work in the series of sculptural markers Buchanan placed in Georgia to memorialize sites of Black presence. Buchanan often explored the concept of ruination to uncover the transformative powers of distress and destruction. These markers symbolically bear witness to the 1803 mass suicide of enslaved Igbo people who collectively drowned themselves off the coast of nearby St. Simons Island. Although their exodus was forced by the traumatic capture and abuse of their bodies, their act of defiance made them free. The work remains visible to the public, though it is not clearly marked and blends in with its natural surroundings.

Tabby was used throughout the American South to construct shacks and quarters for enslaved people. This material functions as a protective shield for Marsh Ruins. Buchanan’s use of tabby, rather than such enduring materials as marble or steel, gestures to the material historically employed to construct Black people’s homes, which she revered. Vulnerable to nature and unstable marsh ground, these forms were intended to be lost to erosion. Buchanan welcomed nature to shift, fragment, and disintegrate her sculptures, knowing that, like the body, they would one day be completely obscured or forgotten. Succumbing to the earth, the materials live on in new forms. Marsh Ruins rejects the representational form of conventional monuments and memorials to speak poetically through the languages of materiality and ephemerality.” (credit)

—

There is also a 96-page book on this artwork.

Omar Mismar, The Path of Love Series

“For a period of 30 days, I took a walk every day, navigating the city using Grindr, a geo-location gay mobile app that tells the users the vicinity of gay men around them. Each day I picked a man I desired, and tried to get as close as possible to him using the app. I kept a record of my routes and traced them into paths.” (credit)

Marina Abromović, Shoes for Departure (1991)

“Shoes for Departure”, an art piece by Marina Abramovic (1991). In her artist statement she says, “Then I have crystal shoes. I have instructions for the public to take off your shoes and, with naked feet, put on the two crystal shoes, close your eyes, don’t move, and make your departure. I’m talking about a mental, not physical, departure. So the public can enter certain states of mind helped by the material itself. Material is very important for me. I use crystals, human hair, copper, iron. The materials already have a certain energy. ” (credit)

(credit)

Mowry Baden, Seat Belt, Three Points (1970)

“Baden’s pieces forced viewers into awkward situations that expressed his interest in kinesthetics — physical perceptions and the changes that took place in neuromuscular memory as the body moved through the work. In Seat Belts (1969-71) Baden explored the difference between what it felt like to walk around a modified circle while tied with a strap from the waist to the floor and what it looked like it would feel like. He wanted to manipulate the “body prints” of the viewers to alter their perceptions of balance, and creating a new “sensory imprint” was his sculptural aspiration. … Baden’s experiments with sculptural-psychological, body-oriented works in the late 1960s and early 1970s would prove to be highly influential on artists such as Charles Ray and Chris Burden, both of whom were his students.” (Schimmel, Paul. “Leap into the Void: Performance and the Object,” Out of Actions: Between Performance and the Object, 1949-1979. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 1998. Page 94.)

- Installation view of Mowry Baden, exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery, March 9 to June 9, 2019

- Installation view of Mowry Baden, exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery, March 9 to June 9, 2019

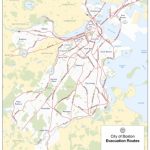

Catherine D’Ignazio, It takes 154,000 breaths to evacuate Boston (2007-9)

(credit)

“Catherine D’Ignazio ran the entire evacuation route system in Boston and attempted to measure the distance in human breath. The project also involves a podcast and a sculptural installation of the archive of tens of thousands of breaths .

The project is an attempt to measure our post-9/11 collective fear in the individual breaths that it takes to traverse these new geographies of insecurity.

The $827,500 Boston emergency evacuation system was installed in 2006 to demonstrate the city’s preparedness for evacuating people in snowstorms, hurricanes, infrastructure failures, fires and/or terrorist attacks.

It takes 154,000 breaths to evacuate Boston consists of:

- a series of running performances in public space (2007)

- a web podcast of breaths (2007)

- a sculptural installation of the archive of breaths (2008)

Website & Podcast

Project Website: www.evacuateboston.com

Archive of Breaths (sculptural piece)

Medium: custom-made table, 26 jars, 26 speaker components, wire, 13 CD players

Dimensions: 45″x72″x16″

I created a sculptural & audio archive of the collection of breaths. There are 26 jars on a custom-made table which correspond to the 26 runs it took to cover the evacuation routes. Each jar size corresponds to the number of breaths from that run. The speaker inside the jar plays the breaths collected from that run. (Better documentation coming soon)

This piece is on view in Experimental Geography, a traveling show curated by Nato Thompson and produced by ICI.

Rebecca Gallo, One Walk Sculptures (2016)

“A series of found object assemblages, each comprising objects collected during a single walk departing from and returning to home. Exhibited in Written In Time curated by Catherine Benz at Delmar Gallery, Ashfield, January-February 2016.” [credit]

“On walking: in mid-2014, I adopted a dog and I started walking. We would walk for at least an hour a day, and she was quick to sniff out scraps of food: half-eaten kebabs, chicken bones, that sort of thing. So, I would scan the ground, trying to spot hazards before she did, and quickly I started to notice other things. Bright coils of wire from electrical repairs; stray nuts and washers; the translucent green of expired whipper snipper cords. Handwritten notes,

packaging moulds and small weights from the rims of car tyres nestled into the crooks of gutters.

Collecting and using found objects was already part of my artistic practice, but the act of walking changed and focused this. A walk came to be told through the haul of items I could hold in my hand or fit in my pockets. Human movement, traced and told through human discards.”

Elinor Whidden, Rearview Walking Stick (2007)

[credit]

Sculptural object used in the Mountain Man performance series in Banff, AB.

Stick attached to rearview mirror.

72×8 inches.

This project brings up concepts of recycling and reuse, visibility in urban and rural spaces, navigation, and safety.

Jazoo Yang, Materials (2017)

epoxy paints, wooden box, 8.9×6.2in / 22.7×15.8cm

collected materials from street in Busan, South Korea, which was disappearing due to development