“C.L.U.E. (color location ultimate experience) is a collaborative video, installation and performance work by artists A.L. Steiner + robbinschilds, with AJ Blandford and Seattle-based band Kinski. The performance and installation-based works have been presented in exhibition and performance venues internationally. The video works range from a single-channel piece (C.L.U.E., Part I), to multichannel pieces, up to 13-channels. ” (credit)

Category Archives: Falling

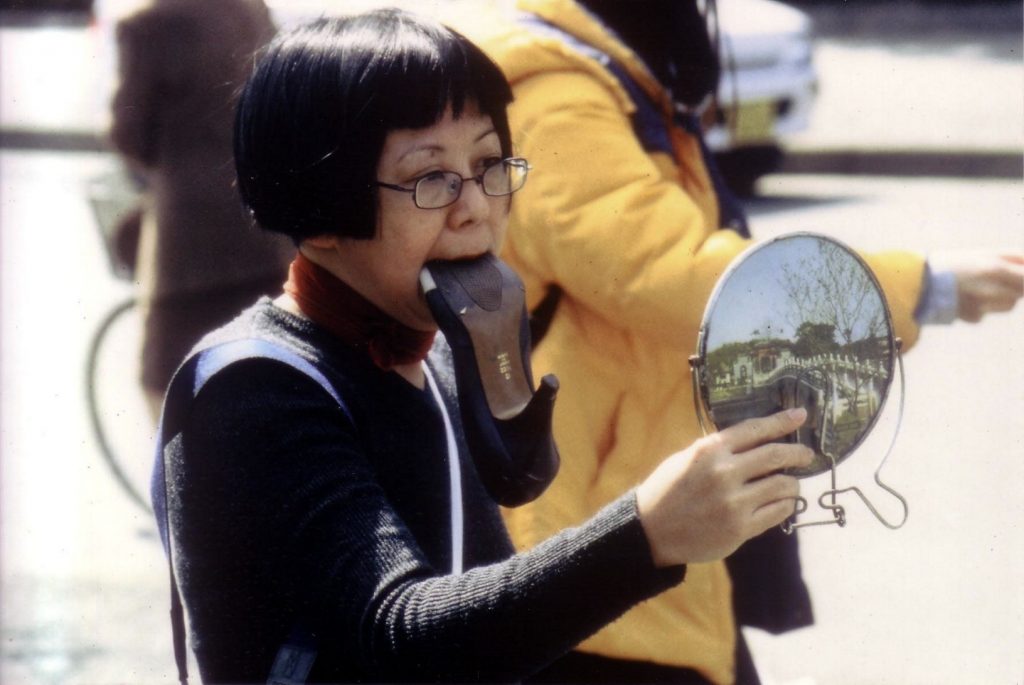

Amanda Heng, Let’s Walk (1999)

Amanda Heng, Let’s Walk (1999)

“Heng has been a central figure in Singaporean performance art as well as feminist discourse in Singapore since the 1980s.

Her body of ‘walking works’ began in 1999 with “Let’s Walk”. She created the work in response to a range of worrying trends, which continue to echo till this day. In 1997, Asia had been hit hard with a financial crisis. Many people lost their jobs and businesses, but women seemed to be the first to get retrenched. Curiously and disturbingly, the beauty business did especially well at this time, as women were pressured to look better than their natural best. In Heng’s own words, “A lot of Singaporean women were ‘upgrading’ themselves, going to beauty salons, having plastic surgery and so on to keep their jobs. A woman’s looks are still worth more than her abilities.”

Your first “Let’s Walk” performance in 1999 was a response to how working women were turning to beauty and cosmetic treatments to keep their jobs during the 1997 Asian financial crisis. What are your thoughts on female beauty?

I prefer to think that beauty is up to each individual. If you claim to be liberated, don’t let others define what beauty is on your behalf. Have the courage to be different from the norm. If you feel such perceptions needs to change, commit yourself to doing something about it and don’t just complain. We women make up half the population in Singapore, so there’s a lot of good that we can do!” [credit]

Later this piece was reprised in 2018 as part of the M1 Singapore Fringe Festival.

Let’s Walk, 2018 is a public participatory performance by Amanda Heng presented at the M1 Singapore Fringe Festival 2018: Let’s Walk. Image courtesy of Amanda Heng.

Trisha Brown, Man Walking Down the Side of a Building (1970)

“The work saw a solitary dancer, secured by harnesses, around the hips and waist, attached to a single cable, walk down the side of the building at a ninety degree angle to the wall. Compelled by gravity, but restrained by the harnesses, hoists and straps used to secure him, the performer exerted considerable effort as he performed the normally mundane task of walking. … Man Walking Down the Side of a Building was one of Brown’s series of ‘Equipment Pieces’, which had initially used mountaineering equipment to construct hoists, pulleys and restraints to enable movement in unusual spaces, or in ways, which put the performers’ bodies at odds with gravity. In keeping with the relative simplicity of the equipment used, Brown also had the performer of this piece wear casual clothing and to perform to the ambient sounds surrounding the building.”

“Her intention was not to create a sense of theatricality but to draw attention to the simple and natural act of walking through a situation in an unnatural scenario. A key element of the work was its instructional nature; while all choreography is arguably instructional at one level, the simplicity of Brown’s instructions – to walk down the side of a building – placed the emphasis on the act of movement, rather than on its motivation or any kind of narrative. No particular instructions were given for how the performer should move, leaving them open to focus entirely on their own physical reaction to the duress of walking in this unusual position. This was characteristic of Brown’s work within the Judson Dance Theatre, which she helped form in the 1960s, and beyond, where she focused on everyday movements and their relation to dance through emphasis on individual gestures. Brown’s creation of choreography which focused on simple, singular movements also facilitated its capacity for re-enactment by making clear the integral elements of the work – a single performer walking down the exterior side of a building – but leaving enough fluidity for the transferal of those actions into different times and spaces.”

“By taking the universally recognisable act of walking and creating a scenario in which that act must be performed differently – in this case, at a ninety degree angle to the normal walking position – Brown remained focused not on the specificities of the space in which the performer acted but the precision of the actions which they undertook. Brown framed an everyday action as choreography and, in then re-contextualising it, drawing attention to the specificity of the movement under stress, she re-framed that action as performance, challenging the audience to consider the expansion of the site of dance into the world around them.”

Trisha Brown, Walking on the Wall (1971)

Trisha Brown – Walking on the Wall 1971

Walking on the Wall (1971) premiered at the Whitney and was performed again in 2010 during the Off the Wall exhibition at the Whitney. Trisha Brown originally performed the indoor work herself with her troupe, involved mounted tracks, ropes, and harnesses.

Trisha Brown – Walking on the Wall 1971 – detail

Catherine Yass “High Wire” 2008

Catherine Yass, High Wire (2008)

[credit]

“‘The dream of reaching the sky is also a modernist dream of cities in the air, inspired by a utopian belief in progress.’ Catherine Yass

Presented in the Berwick Gymnasium is the multi-channel video installation High Wire (2008) by acclaimed British artist Catherine Yass. The work follows the French high-wire artist Didier Pasquette, who was invited by Yass to walk a wire strung between two towers on the Red Road Estate in Glasgow. Stepping out between what were once the highest social housing blocks in all of Europe, Pasquette offers us the ultimate vertiginous perspective.”

[credit] – Duration: 6min, 48sec

High Wire is a room-sized video installation consisting of four projections and two lightboxes. Filmed at Red Road, a high-rise housing complex in Glasgow, it shows the noted French tightrope walker Didier Pasquette attempting to cross from one tower to another over a thin metal wire at a height of 90 metres. The large projections occupy the four walls of the space in which the work is exhibited, offering different views of the event. One shows a long view of the two tower blocks against the distant landscape, highlighting the dominance of the high-rise in its urban context. The second projects footage filmed from the top of one tower, the camera shifting shakily between the roof itself and the line of wire. The third and fourth projections offer further views of the rooftop, one from a distance and one close up. As the films begin Pasquette enters the frame, stepping off a small platform down to the level of the wire. A camera is strapped onto his helmet, revealing the source of the eagle-eye view of the scene, and captures a sweeping, panoramic view to the left, then to the right. It then catches glimpses of Pasquette unclasping his hands and feet, and calmly and purposefully lifting the long pole prepared for him to aid his balance. As he sets off into the void, Pasquette looks down, and his head-camera view provides a reeling, vertiginous sensation. He moves with precision and grace, carefully touching the wire with his toes before resting each foot on it. One third of the way along the wire, Pasquette stops and appears to be in trouble, with the rope shaking beneath him. Retaining his focus, he steps backwards, fast and composed, and in a few seconds he reaches the roof again, his crossing frustrated.

High Wire was made by the British artist Catherine Yass in 2008. It continues a preoccupation, seen in Yass’s earlier work, with architecture and urban systems, in particular the ways in which they can convey wider social and political concerns (see, for instance, her 1994 series Corridors, Tate T07065–T07072, and Descent 2002, Tate T13569). The choice of Red Road was originally a practical one, but it came to symbolise the aspirations of an apparently misconceived architectural utopia. Built in 1964–9 as part of Glasgow City Council’s slum clearance project, Red Road was the tallest residential building complex in Europe at the time. Inspired by the utopian ideas of the architect Le Corbusier (1887–1965), this dream of a brighter future was embraced by the local community. Yet a rise in crime and gang violence, bad maintenance, and perhaps a lack of a sense of ownership and engagement due to the scale of the complex, made residents feel vulnerable and insecure. Red Road became emblematic of the ill-fated housing ambitions seen across Britain in this period. In 2005, three years before Yass made High Wire, Glasgow Housing Association announced a £60 million regeneration plan for Red Road, slating the towers for demolition, to be replaced by around 600 low-rise private and council homes.

High Wire found an immediate resonance within this context, which for some exemplified the failure of the modernist utopian project, and in the installation this is paired with the frustrated attempts by Pasquette to realise his own dream. As Yass stated in 2008:

High Wire is a dream of walking in the air, out into nothing. But it has an urban background and the high-rise buildings provide the frame and support. The dream of reaching the sky is also a modernist dream of cities in the air, inspired by a utopian belief in progress. Every time I see Didier turning back I remember hearing him shout, from where I was standing on another rooftop, ‘C’est pas possible!’ But something was possible, he returned safely. And something emerged from the actuality of the walk, which was a moment when reality became more of a dream than the dream itself.

(Quoted in Glasgow International Festival of Contemporary Visual Art 2008, p.94.)

Yass’s four-screen video installation is accompanied by two photographic works of the same sky walk, printed as black and white negatives and presented on lightboxes. While the videos elicit an empathetic, almost physical response from the viewers, the grey, backlit landscape of the lightboxes presents a world that is unfamiliar and distant.

Further reading

Catherine Yass: High Wire, exhibition catalogue, Glasgow International Festival of Contemporary Visual Art, London and Glasgow 2008.

Sofia Karamani

October 2011

Michael x. Ryan, Roadstains (2007)

[credit]

Roadstains #3: Coke spill from parked car on Potomac Ave. Chicago, Fall 2004 / Installation in process, view #3, Hand cut wood relief: Finnish and Baltic Birch plywood painted with latex paint to match wall color, 2017

Ryan traced spilled drinks in the street as he went walking. He transferred them to wood carvings painted white.

Francis Alÿs, Paradox of Praxis 1 (Sometimes Making Something Leads to Nothing) [1997]

“Paradox of Praxis 1 (1997) is the record of an action carried out under the rubric of “sometimes making something leads to nothing.” For more than nine hours, Alÿs pushed a block of ice through the streets of Mexico City until it completely melted. And so for hour after hour he struggled with the quintessentially Minimal rectangular block until finally it was reduced to no more than an ice cube suitable for a whisky on the rocks, so small that he could casually kick it along the street.”

Janine Antoni, “Touch” (2002)

Janine Antoni, Touch

“The idea of Touch derives from Moor (2001), a work in which the artist created a rope out of her and her friends’ belongings; the artist has said that while she intends to walk it, she also questions the impulse. Touch depicts a literal balancing act in order to suggest the state of perfection that many people strive for, including herself. Antoni has said, “Touch is about that moment or that desire to walk on the horizon,” a location that represents hope and the future. She explained that she wants to walk in “this impossible place, a place that cannot be pinpointed … on the line of my vision, or along the edge of my imagination.” Since the viewer’s involvement is a crucial element in her work, Antoni asks us to imagine ourselves in her situation and contemplate the meaning of the horizon when she is absent from the scene. As the artist teeters but never falls, she accepts and almost embraces a state of imbalance.”

Marcus Coates, “Stoat” (1999)

[credit]

Single Channel Digital Video

Duration: 3 min

Filmed in Grizedale, Cumbria, UK

Camera and sound: Miranda Whall

, Produced by Grizedale Arts

Here Coates attempts to become Stoat, a member of the weasel family. We see him stumbling along a rural stoney track, wearing home made ‘stoat stilts’. A section of 2×4 inch wood strapped to each of his feet with multiple elastic bands are the basis for each shoe, below this though are the two sections of small circular dowling protruding from each which Coates is intent on balancing on. Eventualy, after some ankle turning falls manages to find a way of striding sideways in them. The stilts, replicating the stoat’s paw print dimensions and spacing, create a physical limitation on his body which inadvertently makes his walk not dissimilar to that of a bounding stoat. The stitls are an unconscious mechanism for him to “become’ stoat and move from humanness

Martin Kersels, Tripping (1995)

(credit)

As a large man, Kersels often makes work dealing with his imposing physical presence. He examines stereotypes associated with his gendered body size: clumsy, pathetic, dangerous. These staged photos play into those stereotypes about awkwardness, while the precision of the staging can be interpreted to contradict this reading. (credit: Walk Ways catalog)

—

“Martin Kersels is much larger than most people. He was once described as a “man-mountain” by his friend and colleague Leslie Dick. As a man who stands 6’7” tall and weighs 300 pounds, Kersels draws attention to his body, its size, and the things he’s able to do with it. …

Physicality permeates Kersels’ work. He uses himself as a subject for expressing the emotions we share by virtue of being corporeal. One of these emotions is vulnerability, which Kersels exposes in photographic series that capture him tripping, falling, and riding a bicycle that is too small for his frame. As people, we share embarrassment at the thought of falling in public or in watching someone else trip. However, Kersels’ Tripping series shows us just the thing that embarrasses us. The artist photographed himself tripping on public sidewalks in populated areas and in broad daylight. Tripping highlights Kersels’ desire to connect to others by exposing himself in an embarrassing, although staged, moment. …

Established themes of vulnerability, the body, humor, and playfulness create a thread of continuity among his photographic and sculptural works. …

About the Artist:

Martin Kersels was born in Los Angeles, California in 1960. He began his undergraduate degree in 1978 at the University of California, Los Angeles. After applying to film school and not being accepted, Kersels decided to pursue art history. Kersels then took studio art courses after he decided that art history was not for him; he thought he was a ‘horrible writer.’ He received his bachelors degree in art from UCLA in 1984. After he graduated, he became a member of a neo-dadaist performance art group called SHRIMPS.

Kersels described his performance work with SHRIMPS as movement-based, using very few words and a high level of slapstick comedy, based on the fallibility of the body. Others describe SHRIMPS as a group known for their bizarre costumes and lumbering movements. The women in SHRIMPS were small and muscular and the men were all 6’7” or taller. The first series of SHRIMPS performances were about redefining views of big men being unkind or threatening. The performer Weba Garretson, who later worked with SHRIMPS, described meeting the group by saying, “I was scared of them, even though they seemed like such nice people.” When funding for performance-based art work began to disappear in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Kersels decided to go back to school. In 1993, Kersels was accepted to graduate school at UCLA, where he concentrated on integrating his performance work with the human body with object making.

Kersels received his Master of Fine Arts degree from UCLA in 1995. When Kersels helped the artist Paul McCarthy videotape his performance work, it helped change Kersels’ perspective about making interdisciplinary art. Kersels served as co-director of California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) Program in Art from 1999 until moving to the Yale School of Art in 2012, where he became Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies in Sculpture. Kersels has exhibited his work in major exhibitions including the 1997 Whitney Biennial, as well as in many solo exhibitions.” (credit)