“C.L.U.E. (color location ultimate experience) is a collaborative video, installation and performance work by artists A.L. Steiner + robbinschilds, with AJ Blandford and Seattle-based band Kinski. The performance and installation-based works have been presented in exhibition and performance venues internationally. The video works range from a single-channel piece (C.L.U.E., Part I), to multichannel pieces, up to 13-channels. ” (credit)

Category Archives: topography

Mike Dax, Salt Drawing (2022)

(credit)

SALT from Michael Dax Iacovone on Vimeo.

“Artist Statement:

I like to think of drawing as a broad term, not limited to pencil on paper. Drawing is a record and a representation. It can be a record of what something looks like, or it can represent a location, or an action. It can be a record of an event, or an idea, but it isn’t mistaken for any of these things, it is not a substitute. I draw by moving through spaces based on systems. The artifacts of these journeys are records of those drawings.

I create systems to experience spaces through movement and labor. I make art by creating maps, drawings, photos, and videos that utilize the virtual understandings of space to create systems and formulas to actually experience those spaces. Ideally, the presentation of the formulas and systems along with the visual manifestation of the work will influence the viewers into considering and possibly experiencing their own spaces differently…. but that’s a lot to ask. Maybe someone just wants to look at it, and I’m good with that.” (credit)

Desire Lines

(credit)

desire path, game trail, social trail, fishermen trail, herd path, cow path, elephan path, goat track, pig trail, use trail, bootleg trail

Modelab, Ghost Walker (2014-15)

“Like photography negatives, urban design comprises information on what is not visible and only can be inferred by its contours. In this manner, urban geography becomes a catalogue of defeats and absences that can be interpreted from what once existed.

Based on Mexico City maps from 1867 and 1892, superposed on a 2014 Google map of the Juarez and Cuauhtémoc neighbourhoods, this project seeks to create an appropriation of histories through an artistic and scholar exploration of a specific street that ceased to exist more than a century ago.

Following the techniques of the Situationist’s dérive and Andrei Monastyrsky’s work with the Collective Actions Group, Ghost Walker: An Impossible Walk Through Mexico City’s History is a longitudinal study of a specific urban space, witness of a myriad of processes and modifications throughout 150 years

Ghost Walker (2014-15) has been presented at Muca Roma in Mexico City (2016), and as part of the group exhibition “Walk With Us” at the Rochester Arts Center (2022).

Participants: Sandra Calvo, Ramiro Chaves, Erick Meyenberg, Raul Ortega Ayala, Sergio Miranda Pacheco, Manuel Rocha Iturbide, Modelab.

Modelab is an artistic initiative aiming to promote interdisciplinary projects at the intersection of public space, history, and cartography.

Formed in 2014 by Claudia Arozqueta and Rodrigo Azaola, Modelab projects have taken place in streets, parks, billboards, beaches, museums, vacant retail stores, and other spaces in Australia, New Zealand, France, Mexico, Taiwan, and the Philippines.” (credit)

Beverly Buchanan, Marsh Ruins (1981)

Beverly Buchanan (1940-2015)

“This text originally appeared in ART PAPERS Fall/Winter 2020, Monumental Interventions, as part of a special dossier highlighting seven artists who have fought—and continue the fight—to transform their public spaces by uncovering suppressed histories, resisting oppression, and telling formerly silenced truths.

Beverly Buchanan’s practice referenced southern vernacular architecture to interrogate relationships between Black people, history, and the landscape. In 1981 Buchanan (1940–2015) placed a triangular formation of three sculptural mounds on the edge of the tidal marsh in Brunswick, GA. Titled Marsh Ruins, the large amorphous forms were made by layering concrete and tabby—a concrete made from lime, water, sand, oyster shells, and ash—and then staining the forms brown. This grouping is the most referenced work in the series of sculptural markers Buchanan placed in Georgia to memorialize sites of Black presence. Buchanan often explored the concept of ruination to uncover the transformative powers of distress and destruction. These markers symbolically bear witness to the 1803 mass suicide of enslaved Igbo people who collectively drowned themselves off the coast of nearby St. Simons Island. Although their exodus was forced by the traumatic capture and abuse of their bodies, their act of defiance made them free. The work remains visible to the public, though it is not clearly marked and blends in with its natural surroundings.

Tabby was used throughout the American South to construct shacks and quarters for enslaved people. This material functions as a protective shield for Marsh Ruins. Buchanan’s use of tabby, rather than such enduring materials as marble or steel, gestures to the material historically employed to construct Black people’s homes, which she revered. Vulnerable to nature and unstable marsh ground, these forms were intended to be lost to erosion. Buchanan welcomed nature to shift, fragment, and disintegrate her sculptures, knowing that, like the body, they would one day be completely obscured or forgotten. Succumbing to the earth, the materials live on in new forms. Marsh Ruins rejects the representational form of conventional monuments and memorials to speak poetically through the languages of materiality and ephemerality.” (credit)

—

There is also a 96-page book on this artwork.

Sebastián Díaz Morales, Pasajes IV (2013)

“Sebastián Díaz Morales (1975-), Pasajes IV, Digital video / HD format / 22’40 min on 5:30 hs loop / 2013, 32’’ monitor; Character: Maya Watanabe

This idea follows the same narrative, concept and structure as of former Pasajes video series.

In the so far three Pasajes video works a similar formula repeats on different backdrops: a character unites places through gateways, doors, stairs and roads which would be naturally disconnected from each other. This is the geography of a story expressed in an alteration to the normal, which so far aroused from a montage of urban spaces.

In this proposed formulation of Pasajes the video explores the landscape of Patagonia.

Crisscrossing this territory in the search of the differences on the landscape, a character as a guide, unites different territories disconnected in its geography, as essential pieces of a puzzle to understand this region’s present.” (credit)

Amish Morrell, Henri Fabergé, Christine Atkinson, Epic Ravine Marathon (2015)

ravine

“On November 15, 2015, more than thirty people, including artists, adventure racers, casual joggers, track champions, walkers and other members of the general public, ran from Old Mill subway station in Toronto to Sherbourne subway station, following four major urban watersheds. The route followed the Humber River from Bloor Street to the Black Creek, crossed the North York hydro corridor north of Finch Avenue, joined the West Don River and followed the main artery of the Don River to the finish at Bloor Street, passing under Highway 401 twice. Covering fifty-five km in total, the route took more than 9 hours and almost entirely followed riverbanks and ravine trails. Two people finished the entire distance.”

Credit: Morrell, Amish and Diane Borsato. Outdoor School: Contemporary Environmental Art. Douglas and McINtyre, 2021. Page 62.

—

“Toronto’s ravine system provides city-dwellers with an urban oasis that’s not often explored. But on Sunday, a small group of Torontonians will run a day-long marathon through these expansive green spaces.

Organizer Amish Morrell, who’s the editor of C Magazine, says these runs aren’t competitive. “It’s not a race at all, it’s really an adventure.”

Morrell notes that his friend and performance artist Henri FabergĂŠ started doing conceptual running routes a few years ago. Together, along with artist Jon McCurley, they ran from Kipling to Kennedy (35 kilometres above ground).

About a year ago, Morrell mapped out a marathon route through Toronto ravines – areas that he regularly explores and runs through. He even cross-country skies the ravines in the wintertime. “A lot of this kind of evolved out of finding different ways of moving through the city,” he says.

For Sunday, he’s planned a 55 kilometre trek between the Black Creek, Finch Hydro Corridor and Don River sections of the ravine. “I would say 90 per cent of it is trail in the ravines and about 50 per cent of that is totally kind of secret, clandestine paths,” though Morrell stresses that the event may not be for everyone.

“It’s a pretty DIY, kind of punk event,” he says. Anyone who decides to join needs to be well-prepared with proper equipment and supplies – a detailed list can be found on the Epic Ravine Marathon Facebook page.

And, don’t expect a timed race. “Our motivations are more about exploration, curiosity, discovering places and learning things about them,” says Morrell. He knows the distance may be daunting and expects many of those who join his small group will tag along for the first 10 to 15 kilometres.

Morrell says that while most of the route is accessible via the TTC, being the in the ravines provides an alternate way to view Toronto. “It totally shifts and transforms your experience of the city.”

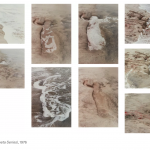

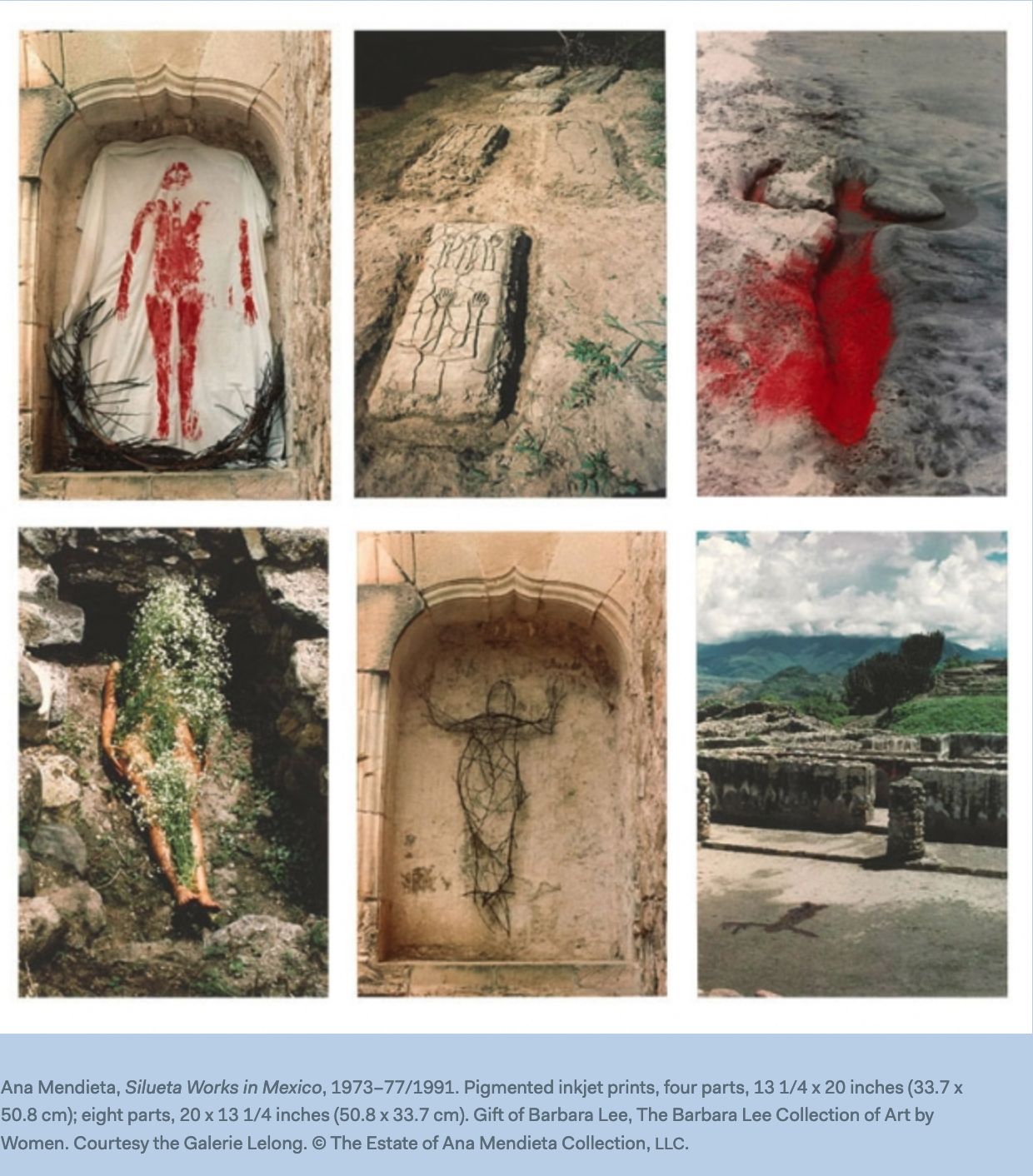

Ana Mendieta, Silueta Series (1973-78)

“The “Siluetas” comprise more than 200 earth-body works that saw the artist burn, carve, and mold her silhouette into the landscapes of Iowa and Mexico. The sculptures made tangible Mendieta’s belief of the earth as goddess, rooted in Afro-Cuban Santería and the indigenous Taíno practices of her homeland. Exiled from Cuba at a young age, Mendieta said that she was “overwhelmed by the feeling of having been cast from the womb (nature).” Seeking a way to, in her words, “return to the maternal source,” she used her body to commune with sand, ice, and mud, among other natural media, as a way to “become one with the earth.”

Yet these works resist easy categorization in form or theme. The “Siluetas” are not self-portraits or performance pieces, except perhaps to the few who witnessed them. Each piece was subsumed by the earth, meaning photographs are the only remaining traces. Similarly, the thematic complexity of Mendieta’s life and these sculptures resist collapsing into neat categories of nation, diaspora, race, or gender. By using the body as both an image and medium, these aspects of identity are complicated. Mendieta’s earthworks occupy a liminal space between presence and absence, balancing the inevitable politicization of the self while searching for meaning in older, sacred traditions. …

The “Siluetas” were an ongoing, ritualistic relationship between Mendieta and the land. I read each work as a spell, a fragment of an ongoing incantation that was not “the final stage of a ritual but a way and a means of asserting my emotional ties with nature,” as Mendieta once said. She wanted to send “an image made out of smoke into the atmosphere,” so that each work was designed to disappear, to be reclaimed by the force she revered in an effort to come closer to it.” [credit]

“Spanning performance, sculpture, film, and drawing, Ana Mendieta‘s work revolves around the body, nature, and the spiritual connections between them. A Cuban exile, Mendieta came to the United States in 1961, leaving much of her family behind—a traumatic cultural separation that had a huge impact on her art. Her earliest performances, made while studying at the University of Iowa, involved manipulations to her body, often in violent contexts, such as restaged rape or murder scenes. In 1973 she began to visit pre-Columbian sites in Mexico to learn more about native Central American and Caribbean religions. During this time the natural landscape took on increasing importance in her work, invoking a spirit of renewal inspired by nature and the archetype of the feminine.1. Ana Mendieta, quoted in Petra Barreras del Rio and John Perrault, Ana Mendieta: A Retrospective, exh. cat. (New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1988), p. 10.

2. Ana Mendieta, “A Selection of Statements and Notes,” Sulfur (Ypsilanti, Mich.) no. 22 (1988), p. 70.” [credit]

Walter De Maria, Las Vegas Piece (1969)

[credit]

“A large, simple etching on the earth, made with four shallow cuts from the six foot blade of bulldozer, two one mile long, two a half mile long, forming a square with half mile lines extending from it. Made in 1969 by the artist Walter de Maria, in a remote location north of Las Vegas, the piece was not maintained, and is only faintly visible today, to some.” [credit]

—

“The question is not whether you can visit Walter De Maria’s Leaving Las Vegas; the question is, does it still exist?

Already in 1972 when discussing the land art project with Paul Cummings, Walter de Maria seemed to emphasize the difficulty of actually experiencing Las Vegas Piece as part of the actual experience of Las Vegas Piece. He’d graded a mile-long square onto a barren desert valley north of the city, and you’d have little chance of even finding it, much less seeing it, much less seeing it all:

it takes you about 2 or 3 hours to drive out to the valley and there is nothing in this valley except a cattle corral somewhere in the back of the valley. Then it takes you 20 minutes to walk off the road to get to the sculpture, so some people have missed it, have lost it. Then, when you hit this sculpture which is a mile long line cut with a bulldozer, at that point you have a choice of walking either east or west. If you walk east you hit a dead end; if you walk west you hit another road, at another point, you hit another line and you actually have a choice.

And on and on for several hours, until your choices and backtracking end in some combination of experiencing the entire sculpture on the ground; declaring victory or defeat partway through; and dying of exposure in the desert because you can’t find your car.” [credit]

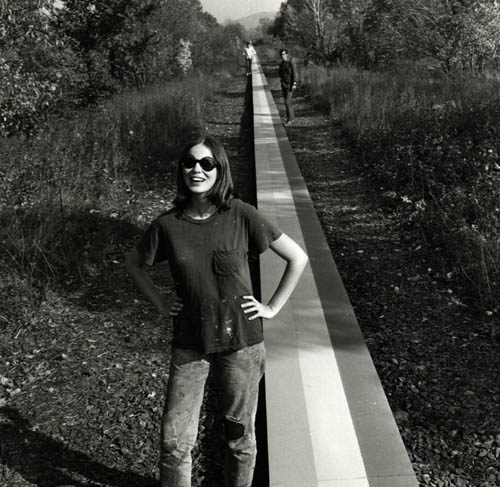

Patricia Johanson, Stephen Long (1968)

Patriciat Johanson (1940-)

“…functions almost like a piece of the landscape—continually reflecting the changes going on around it. 1600-feet long and painted red, yellow, and blue… at times the entire spectrum was visible due to optical mixing along the borders, and the painted colors were constantly in flux due to changes in the color of natural light. At sunset, for example, when red light was falling on the sculpture the blue stripe turned to violet, the yellow stripe to orange. Because the space-projection literally went beyond the field of vision, movement and aerial views also became particularly important.” – © Patricia Johanson, “A Selected Retrospective, 1969-1973”, Bennington College, Vermont, 1973 [credit]

“Inspired by the enormous canvases of the Abstract Expressionists, Johanson created huge sculptures such as Stephen Long (1968) which went beyond the field of vision and interacted with the environment. ” [credit]

Patricia Johanson and assistants assembled “STEPHEN LONG”

along an abandoned Boston and Maine railroad bed in Buskirk, New York, 1968. [credit]