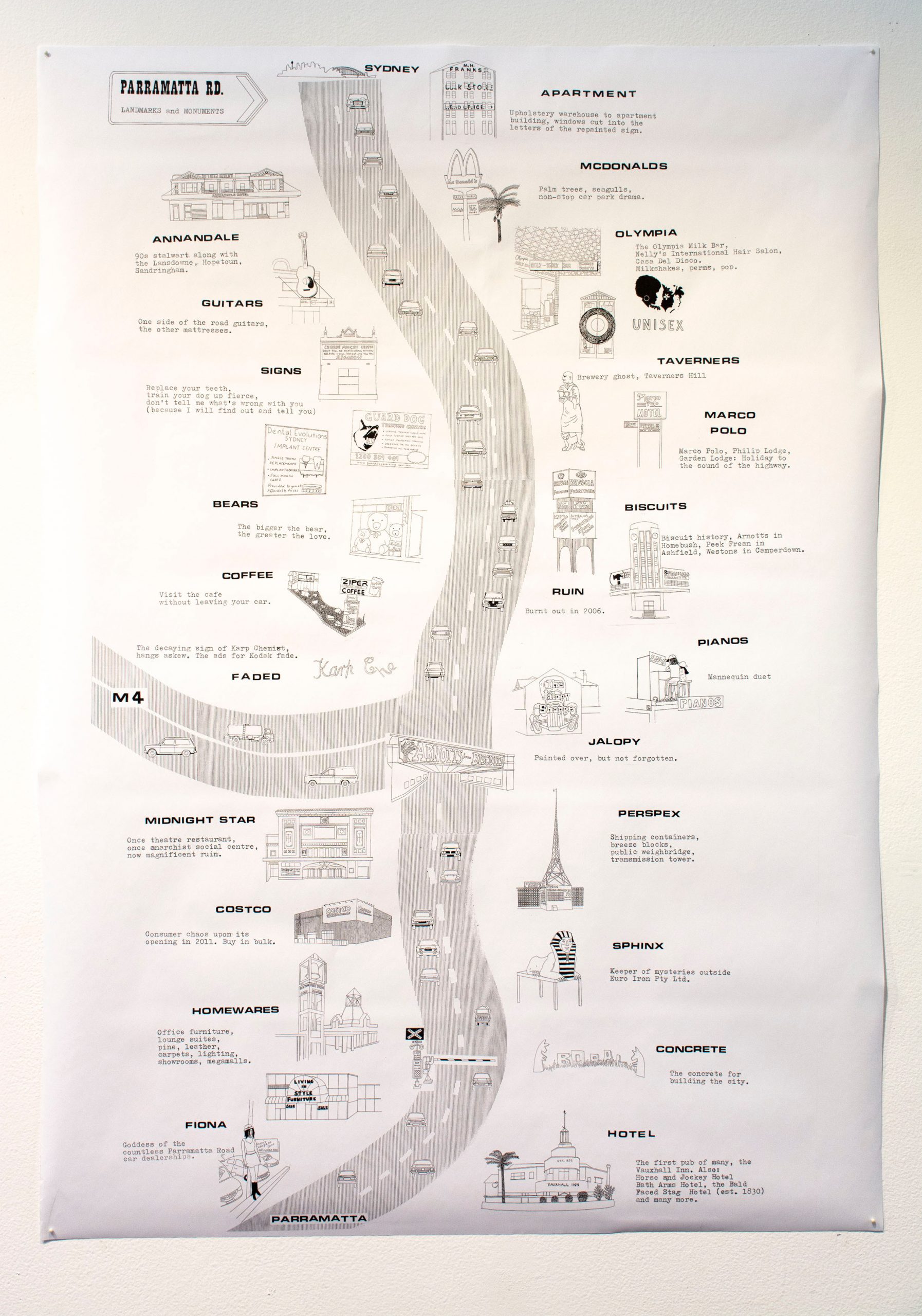

“In the map of Parramatta Road created by Vanessa Berry, quintessential Parramatta Road features like car dealerships and teddy bear stores are elevated to the status of hallowed landmarks. Author of the book Mirror Sydney, and the blog of the same name, Berry explores and reflects the city with the eyes of someone who has traversed it, many times, and looked with intent at the fine details of its fabric and features.” (credit)

Category Archives: Monuments and Memorials

Ken Johnston, Our Walk to Freedom

” Walk to Freedom came about in late 2017 after I discovered the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee was planning remembrance ceremonies in April 2018 to mark the 50th anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination. I recognized the importance of this moment and I thought about how could I contribute to this great event.

I asked myself what could I do to honor the legacy of Dr. King’s ideas? What commitment of myself could I offer the Civil Rights movement today? How could I pay homage to our ancestors who sacrificed so much for our freedom?

That’s when the idea of Walk to Freedom was born. I realized if I was going to offer a symbolic gesture to Dr. King, move the Civil Rights movement ahead by one yard, give thanks to the original Freedom Seekers, then I was going to walk to demonstrate my commitment.” (credit)

Johnston has completed several walks and that timeline is listed here.

Lucia Monge, Plantón Móvil (2010-)

Lucia Monge (1983-)

“Lucia Monge started bringing people and plants together as Plantón Móvil in Lima, Peru. This is a participatory, walking forest performance that occurs annually and leads to the creation of public green areas.

“Plantón” is the word in Spanish for a sapling, a young tree that is ready to be planted into the ground. It is also the word for a sit-in. This project takes on both: the green to be planted and the peaceful protest. It is about giving plants and trees the opportunity to “walk” down the streets of a city that is also theirs. This walking forest performance culminates with the creation of a public green area.

Plantón Móvil started in 2010 while I was walking around Lima, my hometown, and noticing how many trees and plants had their leaves blackened with smog, were being treated as trash cans, or even used as bathrooms. I started to put myself in their place, and thought I would have left town a long time ago. Instead they are sort of forced to sit there and accept this abuse because of their planted “immobile” state. I wondered what it would be like to encounter a walking forest that had taken to the streets like any other group of people would do, demanding respect.

Plantón Móvil, however, is not a group of people carrying plants: at least for that time being we are the forest. I find it important to make this distinction because it changes the nature of the gesture. This is about lending our mobility to plants so that they can benefit from the speed and scale that draws people’s attention. In return; we may momentarily borrow some of their slowness. Essentially, it is about moving-with as a form of solidarity.” (credit)

Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds, Most Serene Republics (2007)

Hock E Aye VI Edgar Heap of Birds, (Cheyenne/Arapaho, 1954-)

This work was a temporary memorial for Native Americans who died in Italy as part of Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show in the late nineteenth century, and was installed at the Venice Biennale in 2007. It consisted of a series of 16 outdoor signs to remember and honor their loss, 8 outdoor signs that serve as commentary, several signs in the water-taxis encouraging repatriation of the Native people’s bodies from Europe to the U.S., as well as a large billboard at the Venice airport that stated ‘welcome to the spectacle, welcome to the show’ as a faux welcoming sign, which was visible as people walked through the airport check point. These Lakota warriors were formerly imprisoned in the U.S. and were given the choice to remain in prison, or go perform in Europe, which was not much of a choice.

Alan Michelson, Mantle (2018)

This work sits at Richmond’s Capitol Square Park in Virginia. The spiral shaped walking path honors the original inhabitants of the region, especially seventeenth-century Chief Powhatan (d. 1618) who united thirty-four Algonquian tribes. The site incorporates cast images of corn, squash, and bean plants around the edge of a reflecting pool, and is surrounded by groves of trees native to the area. The site requires active participation, unlike a statue on a plinth, thereby becoming a reflective activation of this space of reintroduced Native life and cultural memory.

— Michelson, Alan. “Mantle, 2018,” Alan Michelson. Accessed June 25, 2022: https://www.alanmichelson.com/mantle

Robert Smithson, The Monuments of Passaic (1967)

“Six photographs of unremarkable industrial landscapes in Passaic, New Jersey depict evidence of man-made history, yet the title of “monument” seems ironic. Stripped of any apparent artistic agenda, the images appear photojournalistic—without an accompanying news article to inform our perception. Smithson was perpetually intrigued by suburbia; in its sameness he saw a version of eternity defined by formal repetition rather than temporal longevity. By framing the mundane sites as “monuments,” Smithson challenges the conceptions of aesthetic merit and historical significance. Monuments of Passaic exists as three manifestations: a published article in Artforum, a photowork, and a photographic series.” [credit]

Robert Smithson – A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic (PDF)

He drew further attention to site-specificity and the passage of time via his walk along the river and industrial sites.

Dillon de Give, The Coyote Walks (2009-2017)

- Dillon de Give, The Coyote Walks (2009-2017)

- Dillon de Give, The Coyote Walks (2009-2017)

- Dillon de Give, The Coyote Walks (2009-2017)

“An annual walking project that illustrates a connection between New York City and the wild. It was originally performed to commemorate the spirit of “Hal”, a coyote who appeared in Central Park in 2006 and died shortly after being captured and re-released in the forest. The walk begins in the city and remains within sight of a coyote-like path for three days before ending in a relatively wild area. The Coyote Walk has run as an itinerancy, or walking residency since 2014.” [credit]

“It is collaborative research, a retreat (in an almost literal sense), or a mindful holiday. Prospective fellow walkers may share an interest in related subjects, such as urban planning, folk/visual/movement/social arts, biology or other natural sciences. Participants must be prepared for a strenuous walk (approx. 15 miles per day) and for sleeping outside. Please note, differently abled walkers are encouraged to be in touch.” [credit]

Additional images and writing www.coyotewalks.wordpress.com

“I grew up in the Southwest US (Santa Fe, NM— where coyotes are ever-present both as biological entities and as cultural signifiers). I witnessed this event in the media while living in New York City, and continued to think about it in the years following. I began to feel that a larger narrative was looming behind the topical debates. The incident threw the relationship of the city dweller and the natural world into relief. It wasnʼt an abstract suggestion of interconnection between the two; it was a (momentary) unmediated instance of collision– a moment of confusion for both. Hal disrupted a normal state of affairs by presenting himself as an embodiment of something external to our picture of daily life in an orderly civilization. In this he was as comedic as he was threatening. Was this a typical animal or an exceptional one? What was he thinking? And how, exactly, did he find his way into the city?

One way to try to understand this story was to guess about the geography of the journey. The most obvious geographic challenge is the channel of water that separates the island of Manhattan from the mainland of the Bronx– like a moat surrounding a castle. Adrian Benepe, the NYC Parks Commissioner at the time, publicly hypothesized that Hal crossed a small Amtrack trestle bridge over the Spuyten Duyvil Creek at the northern tip of the Manhattan. This became a prevailing theory, but not the only possible one. Other scenarios were equally possible. For example, if Hal had utilized the long Bronx River corridor as a path, he might have crossed over the Harlem River further south and east. Because there were few eyewitness accounts, no camera traps, and no DNA analysis done on Hal, the definite crossing location will remain unknown. This crossing is a big plot point of the story as presented in the media. It came to stand for the dramatic moment in which a cunning trickster privately transgressed from the natural world into the human world. Looking closely at possible routes however, it becomes clear that there were many such crossings.

The Coyote Walks are fueled by curiosity about what it would mean to cross over the line between “the city” and “nature” oneself, to literally connect the two places. The walks are guesses about how coyotes enter New York City that are made with reverse human journeys out of the city. The project began as a kind of memorial to the incident— walked around the anniversary of Hal’s death and initially called the “laH” journey, a backwards spelling of the name. The Coyote Walk is now a time to pose questions about urban life and nature, to learn from the experience of stepping away from the city, and to consider walking practices (human and animal) as imaginative acts.” [credit]

Artist writing:

-

Unpacking (after) a coyote walk. Walking Lab residency, 2017. Link.

-

Connective filaments, coyote walks on the map. Living Maps Review No. 2, 2017.

Link / Download PDF -

Tracking the call of the wild from the heart of Manhattan. NYNJ Trailwalker Summer 2012. Download PDF

Speaking:

-

Artists and the Post Industrial Urban Wilderness, Union Docs, 2017. Link

-

Chance Ecologies Symposium, Queens Museum, 2016. Link

-

Re-inscribing the City: Unitary Urbanism Today, Anarchist Book Fair, 2011. Link

Referenced:

-

Urban Coyotes Spur Walks on the wild side. CUNY NYCity News Service. Audio piece by Samia Bouzid

-

“‘Uurga shig’ – What is it like to be a lasso?” Hermione Spriggs, Journal of Material Culture, 2016. Link

-

Out Walking the Dog blog, Melissa Cooper 2011-12. Link

-

City Reliquary event write up in Matt Levy’s Action Direction blog, 2009. Link

Patty Talahongva, Walk the Indian School (2016)

Patty Talahongva

[credit]

“WALK THE INDIAN SCHOOL” was led by Patty Talahongva on Saturday May 7, 2016, 8am – 10am in Phoenix, AZ. Here is the event description:

“Chances are you’ve taken Indian School Road to drive into downtown Phoenix but do you know how the road got its name? Did you know the federal government operated a boarding school for Native American children for 99 years at the corner of Central Avenue and Indian School Road? Come join us for a walking tour of the former school site, which is now Steele Indian School Park, and learn about the history of such boarding schools and the students and people who lived, worked and played on the site. Three buildings remain from the Indian School and all three are on the National Register of Historic Places. The City of Phoenix owns and operates the park and rents out Memorial Hall for public and private events. Learn about the effort to restore the former music building and turn it into a Native American Cultural Center. The tour will be led by a former student who attended Phoenix Indian School.

Patty Talahongva is the Community Development Manager at Native American Connections (NAC). She is overseeing the restoration of the music building for NAC and its partner, the Phoenix Indian Center (PIC). Patty attended Phoenix Indian School and will share her memories of the school and show guests how the campus changed through the 99-year history. Interview on NPR with Patty about this project. Click here.

Note: We suggest going to the Heard Museum prior to the walk to view the current exhibition on federally run Indian boarding schools. Following the walk we will join Patty at The Frybread House for a meal and a Q & A session. Lunch is on your own and the walking tour is free.”

Jaime Koebel, Indigenous Walks (2014-)

Indigenous Walks Instagram Account

“Jaime Koebel is the founder of Indigenous Walks, “a walk and talk tour through downtown Ottawa that brings awareness about social, political and cultural issues while exploring monuments, landscape, architecture and art through an Indigenous perspective,” according to its website, which is available on internet archive.

Part of the appeal for Koebel—an Indigenous arts activator who also works in traditional and contemporary Métis/Cree art forms such as dance, fish-scale art and beading—is highlighting Indigenous stories that are alternately cloaked, mistold or misrepresented through monuments in Canada’s National Capital Region.

“I open up some information about what each of the monuments is representing, and what each is hiding,” says Koebel.

“We take a look at some monuments that have a clearly Aboriginal theme, like monuments to Indigenous veterans, but there might be some monuments that seem to be Indigenous”—and aren’t.

There are also, Koebel notes, “monuments that seem to have nothing to do with Indigenous people, but there is no information given” about those Indigenous connections.

And on the flipside, there are monuments in Ottawa that seem to be about Indigenous people, “but are actually more about Canada.”

Koebel is well poised to undertake this kind of work—her graduate and undergraduate degrees are in Canadian studies, and she says, “as an Indigenous person having lived in a rural community and moved into an urban centre, that really helps inform my perspective.” She is also practiced in looking at art; Koebel works at the National Gallery of Canada, too, where she was assistant curator on its major survey of Dene-Sauteaux artist Alex Janvier.

Having worked at the National Gallery of Canada as an educator during “Sakahàn,” a massive exhibition of Indigenous art, Koebel sensed that there was a hunger among non-Indigenous people to learn more about Indigenous histories and cultures.

After conducting youth tours of “Sakahàn,” she says, and opening up conversations with youth there about the artworks on view, “what I found so interesting about these conversations was, inevitably, at the end of the tour, I could see these non-Indigenous folks hanging around, and I could see that there was this hunger to know more about Indigenous people.”

For Koebel, walking also aligns with her cultural beliefs around Nehiyawak. This Cree term and concept underlines that there are four parts for human beings—that is, spiritual, physical, emotional and mental aspects of the self.

“The one thread that ties” all of Koebel’s art forms together, she says, “is that they really include all four aspects of what it means for me to be a human being.”

That experience, in part, is what led her to establish Indigenous Walks in 2014. Spring and summer are a particularly busy seasons for the walks, and Koebel also hopes that tour participants right now get a sense of her culture’s values during their experience with her Indigenous Walks team.

“I think when people leave the tour, they get a holistic experience, an understanding of those four parts that together form what it means to be a human being,” Koebel says.” [credit]

Camille Turner, Miss Canadiana Heritage and Culture Walking Tour (2011)

Camille Turner, “Miss Canadiana Heritage and Culture Walking Tour” (2011)

[credit]

“In Miss Canadiana Heritage and Culture Walking Tour, Miss Canadiana acts as a tour guide to the hidden Black histories of Toronto’s Grange neighbourhood. You can View the photo Album here”

- Camille Turner, “Miss Canadiana Heritage and Culture Walking Tour” (2011)

- Camille Turner, “Miss Canadiana Heritage and Culture Walking Tour” (2011)

- Camille Turner, “Miss Canadiana Heritage and Culture Walking Tour” (2011)

- Camille Turner, “Miss Canadiana Heritage and Culture Walking Tour” (2011)

- Camille Turner, “Miss Canadiana Heritage and Culture Walking Tour” (2011)

- Camille Turner, “Miss Canadiana Heritage and Culture Walking Tour” (2011)

““For me, walks really bring awareness to the places that we’re in in a completely different way than any other types of artwork that I’ve seen,” says Toronto artist Camille Turner. “It really makes people see the space in a completely different way, and I think that’s really powerful.”

Turner would know—after creating her soundwalk Hush Harbour, which guides participants on a walk near King and Front Streets in Toronto to reimagine the city’s Black past and to remap Blackness onto the urban landscape, Turner conducted an online survey to get feedback on the piece.

“[The Hush Harbour participants] said they were looking in a new way at the space they walked through every day,” says Turner. “So that way of transforming space is something that walks really do well.”

Currently, Turner is working at one of the formal limits of walking-based art—trying to transform the mobile Hush Harbour walk experience into an installation for the Theatre Centre in Toronto.

“There are limitations to walks as well,” Turner notes, “because people have to come to the place where the walk is made to experience it. I’m trying to uncouple that, so it can be experienced in other places, and travel.”

Turner’s understanding of the power of walking to transform experiences of place started well outside of the art realm.

“I’ve probably gone on lots of different walks, and not necessarily ones that are done by artists,” Turner says, saying one of her favorites was “an amazing walk with Ed Mirvish and Sam the Record Man around Kensington Market” in the 1980s.

Perhaps it is the impact of such experiences that drives Turner to imagine how to make the remapping of space and reclaiming of place available via live, in-person walks, and transform that into something downloadable and reproducible.

For example, Turner has proposed that this year she create a digital version of one of the first art walks she ever did: her Miss Canadiana Heritage and Culture Walking Tour.

Originally performed live in 2011, the piece has Turner, in her Miss Canadiana persona, act as tour guide to hidden Black histories of Toronto’s Grange neighbourhood. (The area is home to the Art Gallery of Ontario and OCAD University, among other canon-building institutions.)

“I am going to do it as a Google Doc so people can actually do it as a self-guided walking tour,” says Turner, who will also remount the work live once more in November 2017.

There may also be a digital or downloadable sound component of the new version of this walk. Turner herself is a great admirer of sonic-walk pioneers like New York’s soundwalk.com, which has created a 9/11 memorial walk with Paul Auster, among other pieces.

“I also really love the sonic walks, because for me, it’s like time travel—you can bring people backward and forward in time,” Turner says. “I use binaural microphones that I put in my ears, so [the recording is] picking up space exactly as I hear it.”

And it’s not just sound technology that is surfacing in Turner’s recent work—in Freedom Tours, a recent collaboration with Cheryl L’Hirondelle for LandMarks2017, Turner organized boat tours around the Thousand Islands area to provide a different kind of mobile storytelling experience. (Turner and L’Hirondelle are also working together on a walk for June 24 in Rouge National Park near Toronto as part of LandMarks2017.)

Ultimately, it is the ability to intervene in history that draws Turner to walking in her practice—especially when it comes to surfacing Black and African experience in spaces constructed by the canon, and by society at large, to read as white or European. (Meetings of past and present Black history also come to the fore in some of Turner’s works in other media, like the combination of contemporary photo-portraiture and historical “runaway slave” notice texts in her series Wanted, co-created with Camal Pirbhai and opening in “Every. Now. Then.” at the Art Gallery of Ontario on June 28.)

“Walking can be an intervention into history—it’s a way of practicing public history, and in bypassing the institutions that create history, you can be a producer of history,” says Turner. “I really like these kinds of ways of working, of intervening in space and in the way that power is kind of written itself in the land.” [credit]