Judith Butler and Sunaura Taylor went for a walk and engaged in a terrific conversation about disability as not merely some physical status but largely a social status, and that is also true for so called “able-bodied” persons.

Category Archives: Disability

Aislinn Thomas, The Slow Walkers of Whycocomaugh (2012)

“Slow Walkers of Whycocomagh and Fast Walkers of Whycocomagh came about to address

what seems like an age-old problem: how to spend time walking with other people who

have an ideal pace different from your own. Negotiating precisely what “slow” and “fast”

looked like on any given day was an interesting part of the experience, as was noticing the different relationships to each other and the landscape facilitated by the different speeds. This piece was originally part of a larger project, the Whycocomagh Skillshare, which was conceived of in response to living in a rural context, in an intentional community that centres people labelled with intellectual disabilities. The skillshare took form as an ongoing series of free workshops, presentations and activities and was an attempt to actively seek out connection, engagement and exchange while challenging normative ideas of expertise and value. Since then, the slow walking groups have taken place in a mall in Mississauga, along rivers and downtown streets in Cambridge and on a mountain trail in Banff.”

Credit: Outdoor School: Contemporary Environmental Art edited by Amish Morrell and Diane Borsato. Page 120.

Christine Sun Kim (LISTEN) (2016)

[CREDIT] – “A Silent Soundwalk, Noisy with Abstract Compositions” via HyperAllergic

Christine Sun Kim during her sound walk (LISTEN) on October 29 (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic unless otherwise noted)

“What is the sound of arms moving? Or of rats gossiping? What about the sound of slight anticipation, or the sound of memories?

These were among the many sounds that artist Christine Sun Kim invited us to consider during “(LISTEN),” a recent soundwalk she led in the Lower East Side organized by Avant.org. We were a group of about a dozen, following her as she visited a handful of sites around the neighborhood to pause, share a personal memory of hers, and offer us an accompanying composition.

But these compositions were technically silent. Serving as audioguides of sorts, they were void of mp3 players, headsets, or other audio devices. Instead, Kim presented a series of textual prompts on an iPad, like flash cards, that described sounds ranging from those that may play immediately in our minds (the sound of a bicycle spinning) to those that are utterly abstract (the sound of an urge to punch someone). Born deaf and originally focused on painting, she has been exploring sound as a medium for nearly a decade and the various ways we may experience and understand it.

“(LISTEN)” readapts Max Neuhaus’s own soundwalk, “LISTEN,” when, 50 years ago, the musician took a small group of his friends on a sonic journey through the Lower East Side. For his iteration, Neuhaus stamped the word LISTEN on his companions’ hands and encouraged them to absorb the familiar noises of the city. As he recalls:

After a while I began to do these works as ‘Lecture Demonstrations’; the rubber stamp was the lecture and the walk the demonstration. I would ask the audience at a concert or lecture to collect outside the hall, stamp their hands and lead them through their everyday environment. Saying nothing, I would simply concentrate on listening, and start walking. At first, they would be a little embarrassed, of course, but the focus was generally contagious. The group would proceed silently, and by the time we returned to the hall many had found a new way to listen for themselves.

Christine Sun Kim during her sound walk (LISTEN)

“(LISTEN)” made me hyper-vigilant of surrounding sounds, but with its designated stops and paired stories, it also brought a more focused approach to Neuhaus’s exercise. At each site, Kim animatedly relayed in American Sign Language the associated memories that her interpreter Vernon Leon spoke aloud. They ranged from her serendipitous encounter with someone who ended up writing her a recommendation for graduate school to a rage-filled bike accident outside the New Museum caused by a negligent cab driver. Outside Audio Visual Arts gallery (currently on hiatus), she recalled experiencing John Andrew’s 2009 exhibition The Now with Before and After. She could not hear its audio component, but she pressed her hands against the room’s yellow walls and through the strong vibrations, experienced the throbbing waves.

The iPad slides that followed such recollections probed our own understanding of sound: descriptions moved from the familiar to the obscure, increasingly prodding individual memories, imaginations, and sensibilities. Short but suggestive, the text pushed sound beyond an experience dependent on hearing; it may be seen or felt, as Kim made incredibly clear as she invited us so associate it with the material and texture (“the sound of pavement floor”); with moments (“the sound of condensation”); with emotional states (“the sound of uncertainty”); and with action and restraint (“the sound of not trying to smell”).

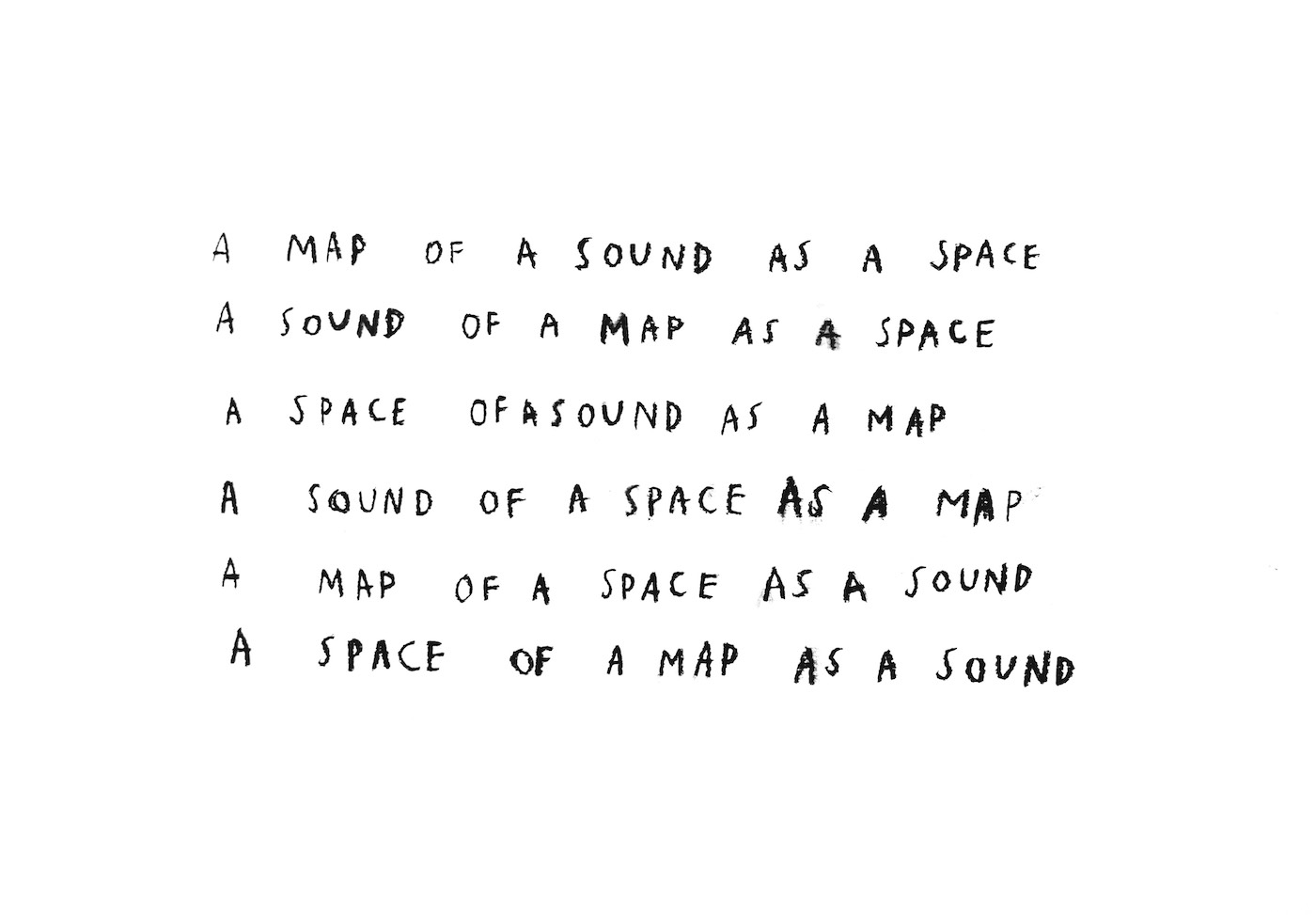

Christine Sun Kim, “a map of a sound as a space” (2016) (image courtesy Avant)

Parentheses often appear in Kim’s visual works, which deal largely with text. The coupled curves appeared in “(LISTEN),” too, bookending each phrase she showed. When anchored in the space between the two lines, words and their sonic implications are visually isolated and highlighted yet are also reduced in both presence and volume. The physical pockets of the neighborhood Kim carved out on her soundwalk worked similarly, becoming temporary spaces for each of us to consider the subjectivity of experiencing sound, which extends beyond the use of just a single sense.

We ended “(LISTEN)” at a quiet creperie next to a boisterous bar, where Kim crossed out the word stamped on each of our hands. As I walked away, my ears picked up the rough grating of a trash can hobbling across park gravel; the metallic tinkling of a trotting dog’s leash nudging its collar.

(LISTEN) took place on October 29 and October 30 around the Lower East Side.”

Raquel Meseguer Zafe, A Crash Course in Cloudspotting (the subversive act of horizontality) (2020-)

While laying down might feel like the antithesis of walking, this is an important project highlighting the need for rest and disability awareness for participants struggling with chronic illness and fatigue.

“A Crash Course in Cloudspotting is an intimate audio journey exploring the depths of human connection and the subversive act of lying down.

Over the past four years Raquel Meseguer Zafe has collected over 250 stories from people living with invisible disabilities and chronic illnesses around the country. This immersive audio installation invites you into the heart of these personal experiences by weaving together some of the stories and voices. In this delicate and beautiful space, Coventry residents and participants from across the UK and Europe, will illuminate your horizontal journey with a gentle choreography of lights, activated in the space by patterns of rest we so rarely see.

“A Crash Course in Cloudspotting is about finding, making, and acknowledging the connections between people….the show lets us imagine ourselves as part of a web reaching out across the world.” Exeunt Magazine.

This installation & live performance project, includes Relaxed performances, Audio Description and Touch Tours. The Cloudspotting Digital Archive is available online.

Raquel Meseguer Zafe is a UK based dance theatre practitioner. She acknowledges ‘crip’ as a tool in her artistic process, and ‘rest’ as a creative impulse. Raquel is the artistic director of Unchartered Collective, a Lost Dog Associate Artist, and a Pervasive Media Studios Resident. Her work is supported by Unlimited and MAYK.

Conceived by Raquel Meseguer Zafe. Devised in collaboration with Artist & Theatre Designer Sophia Clist, Composer & Sound Artist Jamie McCarthy, Associate Artist Laura Dannequin, Artist & Designer Tom Metcalfe, Sound Designer Charles Webber. Software Developers David Haylock & Joseph Horton.” [credit]

Moira Williams, Fissures, Holes, Limbs: Breathing Dislocated Scales (2019)

“Fissures, Holes, Limbs: breathing dislocated scales is an eco somatic sound walk centering disability.

I-Park Kicks off Seventh Art Biennale in East Haddam

BY CATE HEWITT, SEPTEMBER 23, 2019 ART & DESIGN

EAST HADDAM — At night, animals, birds, flowers, and even mushroom spores become active, moving about, making sounds and leaving traces, mostly unbeknownst to humans.

Participants in artist Moira Williams’ sound walk called “Fissures, Holes, Limbs: breathing dislocated scales,” were invited Sunday to shift from “daylight to moonlight” and experience night sounds and images she had recorded onsite at I-Park, an international artist-in-residence program founded in 2001.

Williams, a New-York-City-based artist, is one of nine artists in I-Park’s seventh Site-Responsive Art Biennale who spent three weeks on the program’s 450-acre campus “creating ephemeral artworks that respond to the property’s natural and built environments,” according to the program notes. The artists’ works can “take the form of environmental sculptures, videos, aural experiences or performance pieces.”

At the beginning of Williams’ sound walk, participants were asked to choose a stick from a number of precut tree branches, mostly about five or six feet in length. These branches were used as “limbs,” extensions of the human body, to explore holes and fissures in the path, as well as rocks and lichen.

After the band of sound walkers set off along a path, Williams stopped the group at a field and played a recording she had made while camping onsite of an owl hooting.

“Think of how the owl moves so quietly throughout the night and what it disturbs and what it accentuates, think of the different way our breath moves and accentuates as well, think of the spores and the seeds that we never see that we move,” she said.

She asked the group to face the field and to lift up their shoulders and think about them as wings, with the limb as an extension of sorts.

“Think about how they feel in the air and what you can move and what you can share and extend,” she said. “If you have a limb, an extra limb with you, please raise your limb in any way that you like, and think of your shoulders and your extra limb, think of the breeze going through your shoulders and your extra limb.”

Dressed in a white hazmat-type suit embellished with bright neon stripes made from tape, Williams carried a roll of black wire on one shoulder, like a techie epaulet, and a small speaker and projector connected to her mobile phone in a pouch around her waist. On her head was a wide “hat,” made from a piece of flat white painted cardboard with a space cut out for the top of her head, and long neon green streamers attached at each end that trailed behind her when she walked.

As the group proceeded down the path, Williams removed her hat and projected a tiny video of a fox she had recorded at night, letting the walkers experience the sight and sound as they hiked past.

She asked everyone with “an extra limb” to use it to touch the rocks, holes and lichen along the path, as a way to experience the site.

Soon the group came upon a field where Williams had created a labyrinth.

“Choose a path and walk to where you can find a white stump,” she instructed. “We’re under a full moon in the middle of the night, it’s an extraordinary full moon.”

Soon the group gathered around a white stump that had holes drilled in it about the size of the limb walking sticks. She asked those who had limbs to share them with those who were without.

“Those who haven’t had an extra limb, think of the limb that they now have and how the previous person used that limb and what that means to them not to have it now,” she said. “And think about whether the bark is smooth and whether there’s holes or fissures or lichen or even insects on your limb.”

Williams invited everyone holding a limb to place it in one of the holes in the stump, which created a kind of tree sculpture. The new tree symbolized connection, she said, and could forge a new identity for everyone who took part.

“If you walked with an extra limb and want to think about if you have a new name, you can say your new name out loud if you do have one, or if you can think of a new name that might incorporate an extended limb,” she told the group. “My new name would be Lichen.”

Of the 20 participants, names like Woody, Meadow, Shaggy, Hiawatha and Tripod emerged.

Then Williams directed the walkers’ attention to the far side of the meadow where a large tree with bare branches reached to the sky, a living reflection of the group’s tree made from limbs.

“Look at the tree in front of us and think about the tree behind us and the juncture of all of us connecting all of us,” she said.

Williams next led the group to a boardwalk that snaked through a marshy area with numerous streams flowing along the ground.

At one point she stepped out of the path and projected a video of mushrooms sporing onto a series of white vertical boards that were set in the marsh.

“This is an image of sporing mushrooms that only spore at night and these are things we seldom get to see,” she said. “They’re just ghostlike spores that we’re gathering on our own bodies and sharing with the rest of the world.”

Williams, who holds a BFA from the School of Visual Arts, a graduate certificate in “Spatial Politics,” and an MFA from Stony Brook University, said her underlying interest is about “making the environment accessible to all people, especially people with disabilities.

“It’s about thinking in ways that are not about independence but more about connectedness with the environment and one another,” she said. “It’s connectedness as a holistic ecosystem, we’re not just this very big myth about how we’re independent.”

She explained that her white outfit reflects a philosophy of healthcare — “the idea of nursing and empathy and being a caregiver.”

“I think of myself as a steward caregiver. I love wearing the white suit because I’m in the lead and I want people to see me,” she said. “The hat is a device to say, hey, here I am, come and join me, but it’s also the width of walkways that need to be for people that need a wheelchair.”

By walking through the marsh and the woods, participants will carry traces of the environment to new places, she said.

Near the end of the path, Williams crouched down, removed her hat and projected a time-lapse video of a lotus flower opening and closing at night on the pond at I-Park, a film she made while floating on the water.

The tour was over and she bade the group good-bye by saying, “Good morning everybody.””

Mindy Goose, Art, Access and Urban Walking (2017)

Mindy Goose, Art, Access and Urban Walking (2017)

“On Saturday 7th October, I led a walk as part of the Love Arts Festival 2017 programme.

The ‘Art, Access and Urban Walking’ grew out of the walk I led as part of Jane’s Walk Leeds in May. The idea was to create conversation around accessibility in urban and green spaces, and document it in a creative way through photography, writing, sketching, or spoken word. There were so many snippets of conversation I wish I had recorded, about the spaces we occupy, how we neglect visiting areas outside our neighbourhood; and once we hit the shopping park, conversation moved towards accessibility in public spaces.” [credit]

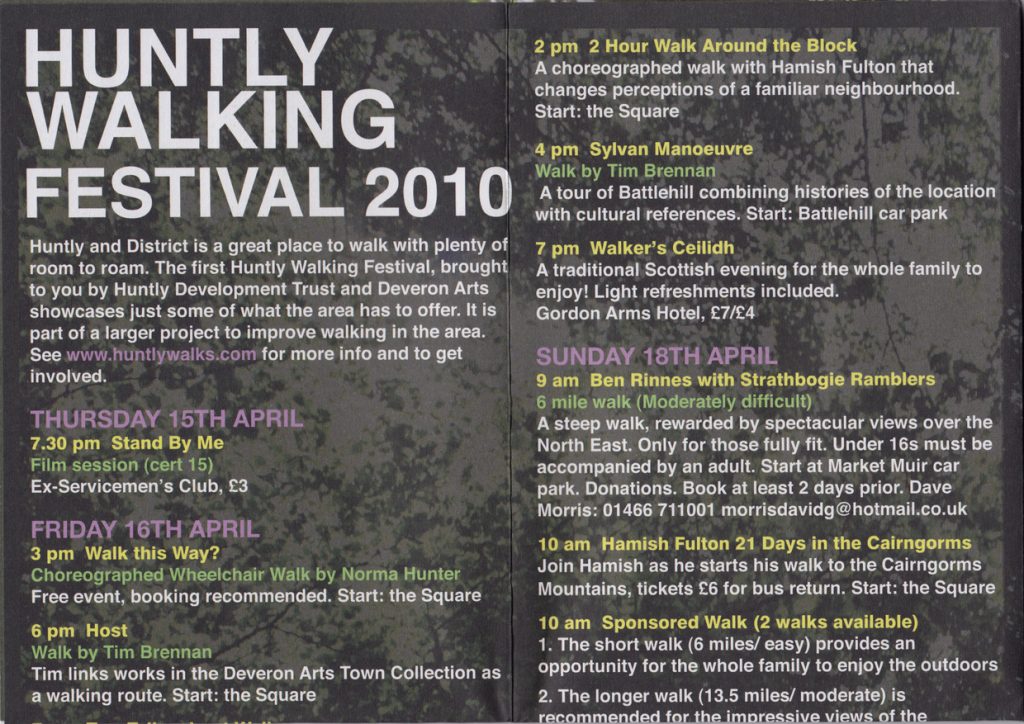

Norma Hunter, Walk this Way (2010)

Norma Hunter, Walk this Way (2010) [credit]

Amanda Heng, Every Step Counts (2019)

- Amanda Heng “Every Step Counts” (2019)

- Amanda Heng “Every Step Counts” (2019)

- Amanda Heng “Every Step Counts” (2019); Passers-by looking at the video of Amanda Heng’s work projected onto the walls in the Esplanade tunnel.

Multi-disciplinary project: workshop, text work in public space, archival footage, video projection and live performance

Dimensions variable

Collection of the Artist

Singapore Biennale 2019 commission

“Contemporary artist, curator and lecturer Amanda Heng (b.1951, Singapore) is known for making art that explores real-world issues through everyday activities – whether it’s walking, peeling beansprouts, or having coffee. Her recent work for the Singapore Biennale, titled Every Step Counts, draws upon the act of walking and takes an introspective look at the ageing body and how it is impacted by the rapidly evolving social and cultural environments.

Every Step Counts is a project spanning May 2019 to March 2020. The work comprises a two-day walking workshop, a text work, archival footage, a video projection and a series of live performances. The larger-than-life text work is featured on SAM’s hoarding along Bras Basah Road, while the video projection is exhibited at the Esplanade tunnel, joining the line-up of outdoor artworks displayed during the Singapore Biennale 2019.

WALKING IS A CENTRAL FEATURE IN MANY OF AMANDA HENG’S WORKS

Influenced by the Taoist principle of “working with rather than against nature”, Amanda sees walking as a form of meditation, a ritual from which to draw inner strength.

“It has to do with my intention of examining the body, which is an important element in live performances. The body is actually a live organic element that grows and gets old. This aged body – how should I look for the continuity of practising, of using it?”

KEEPING THINGS SIMPLE YET MEDITATIVE

Doing away with all bells and whistles, Amanda chose to present her work as a single line of text standing as a backdrop against a busy street; blue to represent the sky – a constant to anyone, anywhere; white to uplift; and bold italics to represent spirited movements. She hopes its simplicity will stop people in their tracks to savour the words amidst the hustle and bustle of life.

THE AUDIENCE COMES FIRST

Every component of Every Step Counts engages people in different ways. The workshop, for instance, involved nine participants spending two days charting their own routes of walking, who later had their walks filmed and are now being projected onto the walls of the Esplanade tunnel. It is hoped that when passers-by walk alongside these participants, albeit in a different space and time, they will become more attuned to their surroundings and their own pace.” [credit]

“Every Step Counts is exhibited at Singapore Art Museum on the hoarding, as well as Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay. This work also comprises a series of performances.

Amanda Heng invites participation and intimate conversations in her performative works. Often, she harnesses everyday situations to explore issues like the complexities of labour or the politics of gender. For her project in this Biennale, Heng revisits her ‘Let’s Walk’ series, first performed in 1999. Drawing upon the act of walking, the artist moves forward, looks back, turns inward and ventures outward with others. In this piece, she returns to the seminal scene of the walk and facilitates a workshop with people who chart their own routes of walking, and with whom she walks. In so doing, she generates reflections and perspectives, as well as comes to terms with the limits and stamina of the aging body.” [credit]

Carmen Papalia, White Can Amplified (2015)

Carmen Papalia, “White Cane Amplified” (2015)

[credit]

“Realized in East Vancouver in 2015 as part of the experiential research that Carmen Papalia undertook prior to his collaboration with Sara Hendren’s Adaptive and Assistive Technologies Lab at Olin College of Engineering, White Cane Amplified is an improvised process in which Papalia replaces his detection cane with a megaphone that he uses to identify himself and hail support from passers-by. An effort to reclaim the social function of the white cane, the process is an opportunity for Papalia to practice accessibility and disclosure as an ongoing exchange with his community.”

Clare Qualmann, Perambulator (2012-)

Via Qualmann: Perambulator is an ongoing artwork that explores the experience of walking with a pram (or pushchair, stroller or buggy). Working from an auto-ethnographic standpoint the project explores gendered spaces, maternal narratives and shifting identities, inequality and mobilities. Elements of the work have been produced for Lewisham Arthouse, London, Deveron Projects, Huntley, and Flux Factory, New York.

Please visit the perambulator website for more information: https://huntlyperambulator.wordpress.com/