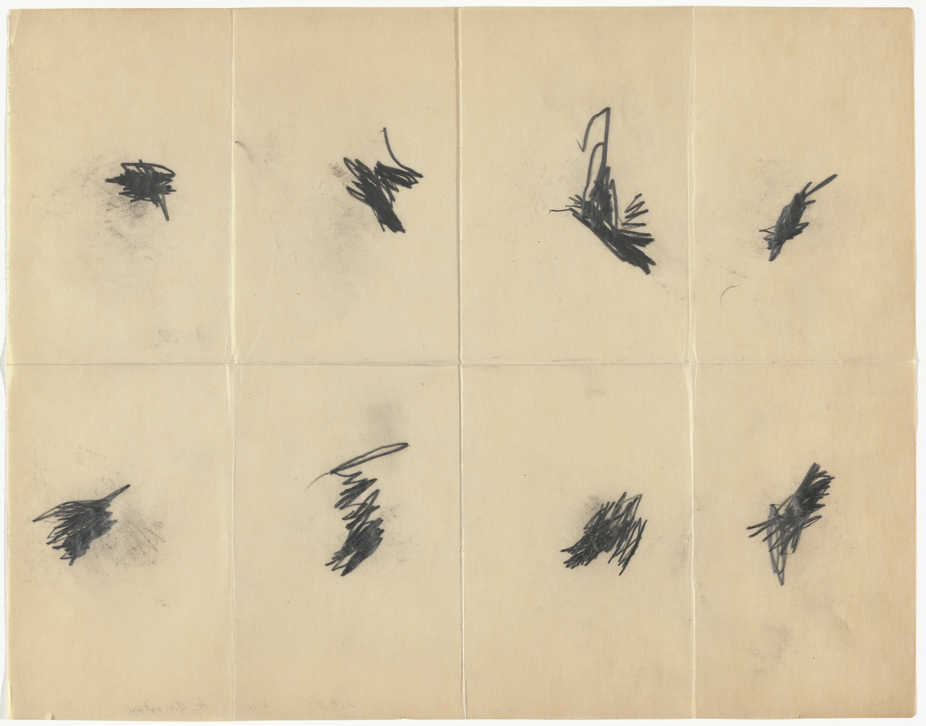

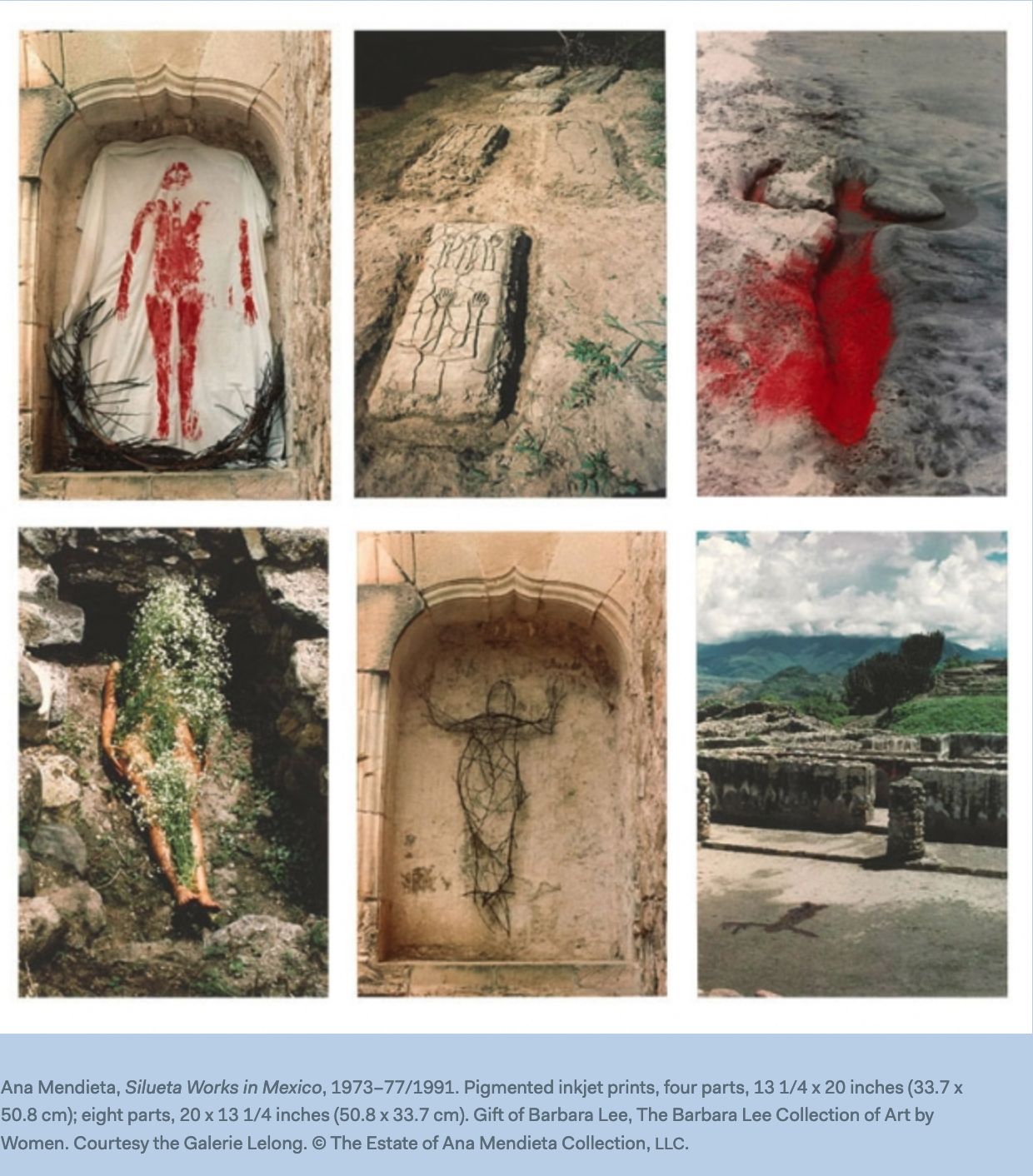

“The “Siluetas” comprise more than 200 earth-body works that saw the artist burn, carve, and mold her silhouette into the landscapes of Iowa and Mexico. The sculptures made tangible Mendieta’s belief of the earth as goddess, rooted in Afro-Cuban Santería and the indigenous Taíno practices of her homeland. Exiled from Cuba at a young age, Mendieta said that she was “overwhelmed by the feeling of having been cast from the womb (nature).” Seeking a way to, in her words, “return to the maternal source,” she used her body to commune with sand, ice, and mud, among other natural media, as a way to “become one with the earth.”

Yet these works resist easy categorization in form or theme. The “Siluetas” are not self-portraits or performance pieces, except perhaps to the few who witnessed them. Each piece was subsumed by the earth, meaning photographs are the only remaining traces. Similarly, the thematic complexity of Mendieta’s life and these sculptures resist collapsing into neat categories of nation, diaspora, race, or gender. By using the body as both an image and medium, these aspects of identity are complicated. Mendieta’s earthworks occupy a liminal space between presence and absence, balancing the inevitable politicization of the self while searching for meaning in older, sacred traditions. …

The “Siluetas” were an ongoing, ritualistic relationship between Mendieta and the land. I read each work as a spell, a fragment of an ongoing incantation that was not “the final stage of a ritual but a way and a means of asserting my emotional ties with nature,” as Mendieta once said. She wanted to send “an image made out of smoke into the atmosphere,” so that each work was designed to disappear, to be reclaimed by the force she revered in an effort to come closer to it.” [credit]

“Spanning performance, sculpture, film, and drawing, Ana Mendieta‘s work revolves around the body, nature, and the spiritual connections between them. A Cuban exile, Mendieta came to the United States in 1961, leaving much of her family behind—a traumatic cultural separation that had a huge impact on her art. Her earliest performances, made while studying at the University of Iowa, involved manipulations to her body, often in violent contexts, such as restaged rape or murder scenes. In 1973 she began to visit pre-Columbian sites in Mexico to learn more about native Central American and Caribbean religions. During this time the natural landscape took on increasing importance in her work, invoking a spirit of renewal inspired by nature and the archetype of the feminine.

By fusing her interests in Afro-Cuban ritual and the pantheistic Santeria religion with contemporary practices such as earthworks, body art, and performance art, she maintained ties with her Cuban heritage. Her Silueta (Silhouette) series (begun in 1973) used a typology of abstracted feminine forms, through which she hoped to access an “omnipresent female force.”¹ Working in Iowa and Mexico, she carved and shaped her figure into the earth, with arms overhead to represent the merger of earth and sky; floating in water to symbolize the minimal space between land and sea; or with arms raised and legs together to signify a wandering soul. These bodily traces were fashioned from a variety of materials, including flowers, tree branches, moss, gunpowder, and fire, occasionally combined with animals’ hearts or handprints that she branded directly into the ground.By 1978 the Siluetas gave way to ancient goddess forms carved into rock, shaped from sand, or incised in clay beds. Mendieta created one group of these works, the Esculturas Rupestres or Rupestrian Sculptures, when she returned to Cuba in 1981. Working in naturally formed limestone grottos in a national park outside Havana where indigenous peoples once lived, she carved and painted abstract figures she named after goddesses from the Taíno and Ciboney cultures. Mendieta meant for these sculptures to be discovered by future visitors to the park, but with erosion and the area’s changing uses, many were ultimately destroyed. While several of these works have been rediscovered, for most viewers the Rupestrian Sculptures, like the Siluetas before them, live on through Mendieta’s films and photographs, haunting documents of the artist’s attempts to seek out, in her words, that “one universal energy which runs through everything: from insect to man, from man to spectre, from spectre to plant, from plant to galaxy.”²Nat Trotman

1. Ana Mendieta, quoted in Petra Barreras del Rio and John Perrault, Ana Mendieta: A Retrospective, exh. cat. (New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1988), p. 10.

2. Ana Mendieta, “A Selection of Statements and Notes,” Sulfur (Ypsilanti, Mich.) no. 22 (1988), p. 70.” [credit]