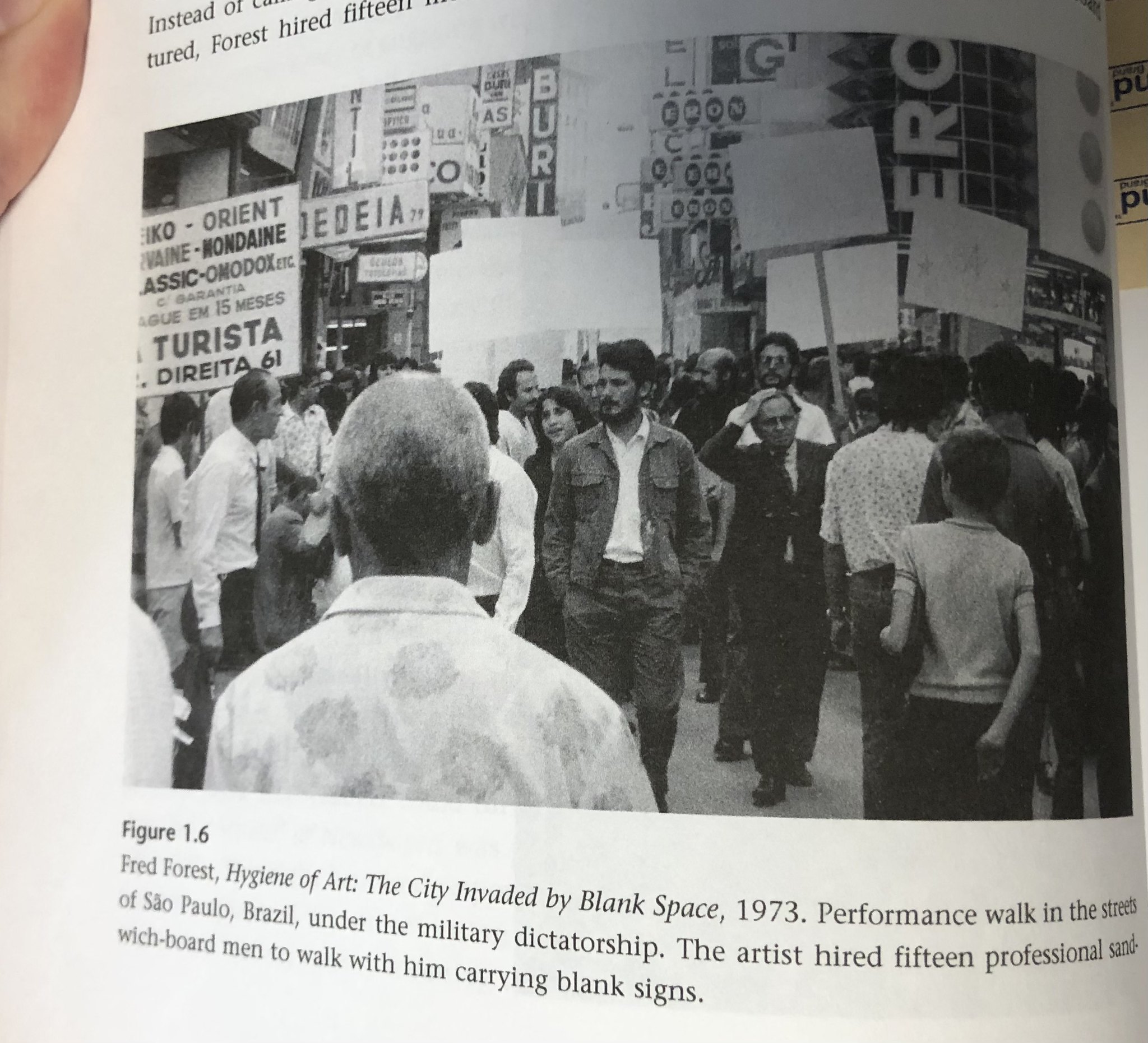

Fred Forest, Hygiene of Art: The City Invaded by Blank Space (1973). Photo of page from “Walking and Mapping: Artists as Cartographers”

This was a performance walking by Fred Forest in the streets of São Paulo, Brazil under the military dictatorship. The artist hired 15 professional sandwich board men to walk with him carrying blank signs.

“The goal of this series of provocative actions undertaken under the cover of art was to create symbolic/utopian spaces of popular free expression in the mass media and the street in defiance of the ruling military junta. Elements included a nationwide call-in operation using specially installed telephone lines, blank spaces for reader response published in several newspapers, the use of radio and television to orchestrate unusual experiments in public participation (e.g. a taxi rally through the streets of the city), a videographic “mini museum of consumerism,” and a street demonstration in which participants carried blank signs: “The City Invaded by Blank Space.” This last endeavor led to the artist’s arrest by the political police.” (credit)

12th SAO PAULO BIENNIAL

OCTOBER 1973- AWARDED THE BIENNIAL’S GRAND PRIZE IN COMMUNICATION