Kristina Borg, The Cities Within (2016) Alternative DIY Walk – Vienna, Austria

“In 2016, the methodology and practice outlined in the previous section (Alternative DIY Walks) resulted in the project The Cities Within. This walk was specific to the city of Vienna (Austria), precisely to the neighbourhoods of Leopoldstadt and Favoriten, the 2nd and the 10th districts respectively. This project was made possible as part of the Artists in Residence programme of the Austrian Federal Chancellery and KulturKontakt Austria, and also supported by the Cultural Export Fund of Arts Council Malta.” (credit)

“Alternative DIY Walks

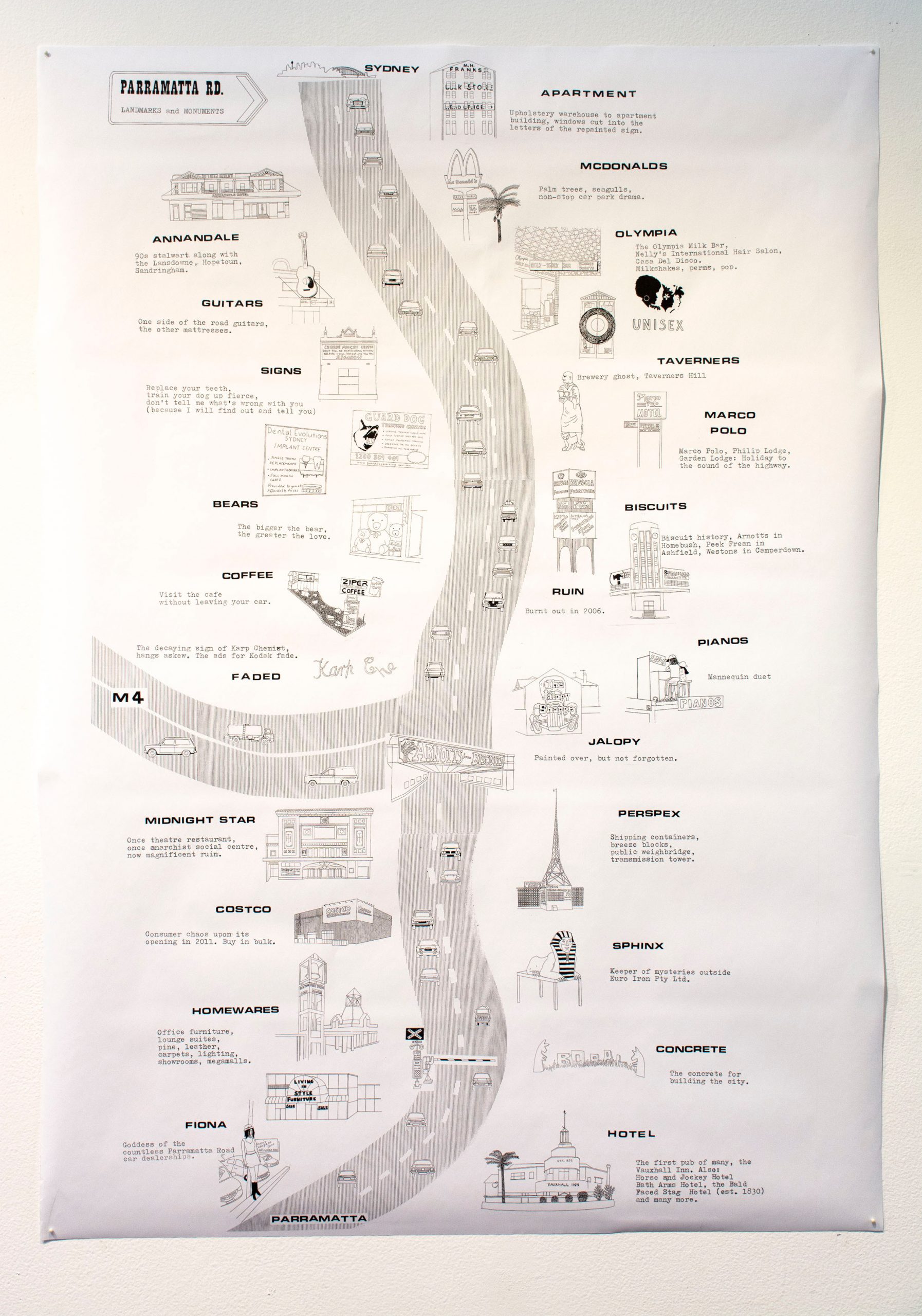

These alternative do-it-yourself walk-tours are specific to different cities. Starting off with a series of conversations with a number of locals, the artist gains knowledge about their day-to-day experience of their city. Gleaning information from these conversations, together with onsite-research walking, the artist maps-out a number of hidden and/or neglected spaces, significant to personal and collective memory, so as to create a fictional-narrative based on a mix of fantasy and reality.

The narrative forms basis for a sound-walk that takes the shape of a do-it-yourself walk-tour and invites the participant/walker/wanderer to enter a one-to-one relationship with that city. Through a combination of recorded found, ambience sounds and a voiceover narration, one is guided through different neighbourhoods, streets, spaces and places. This project purposefully moves away from the city touristic centre and focuses on the outer districts/areas which more often than another are neglected by authorities. During such one and a half to two hour walks one passes through streets and places that are not always so common, but are significant to the daily lives and memory of the local inhabitants. Each DIY walk is also complemented with a series of illustrated maps, presented in the form of a booklet, which help indicate the way as well as when to play or pause the audio. From time to time the audio is paused so as to get a live experience of the place here and now.

Through this mix of fantasy and reality it is up to the participant/walker/wanderer to decide how to interpret the narrative, whether to take it as a fact, a metaphor or a dream. ” (credit)