“he scrapes and smears dozens of layers of paint across massive canvases using a giant squeegee.” [credit]

“he scrapes and smears dozens of layers of paint across massive canvases using a giant squeegee.” [credit]

“Helen Frankenthaler (Dec. 12, 1928 – Dec. 27, 2011) was one of America’s greatest artists. She was also one of the few women able to establish a successful art career despite the dominance of men in the field at the time, emerging as one of the leading painters during the period of Abstract Expressionism. She was considered to be part of the second wave of that movement, following on the heels of artists such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. She graduated from Bennington College, was well-educated and well-supported in her artistic endeavors, and was fearless in experimenting with new techniques and approaches to art-making. Influenced by Jackson Pollock and other Abstract Expressionists upon moving to NYC, she developed a unique method of painting, the soak-stain technique, in order to create her color field paintings, which were a major influence on such other color-field painters as Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland.

One of her many notable quotes was, “There are no rules. That is how art is born, how breakthroughs happen. Go against the rules or ignore the rules. That is what invention is about.”” [credit]

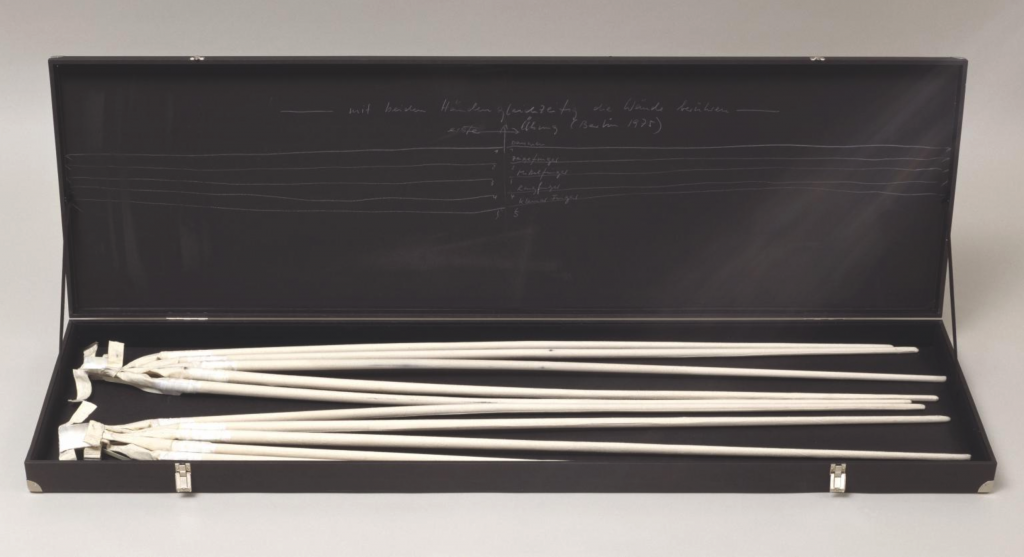

Unicorn appears in Horn’s 1970 film of the same name, and in her 1973 film Performances II.

“Unicorn is a white sculpture designed to be worn by a female performer. A series of vertical and horizontal white fabric straps serve as a kind of bodice that binds the performer’s naked body, with further straps connecting the neck to a tall, conical, horn-like structure that extends vertically from the top of the performer’s head. In an interview in 1993 Horn explained the development and original manifestation of this work, one of her earliest sculptures for the body:

[I had a vision] of this woman, another student. She was very tall and had a beautiful way of walking. I saw her in my mind’s eye, walking with this tall, white stick on her head which accentuated her graceful walk. I was very shy, but I started talking to her and proposed that I measure her to build this body-construction that she would have to wear naked and that would terminate in a large unicorn horn on her head. To my surprise she agreed … I invited some people and we went out to this forest at four AM. She walked all day through the fields … she was like an apparition.

(Quoted in Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum 1993, p.16.)

Developed from a 1968–9 preparatory sketch (Tate T12783), Unicorn is part of a series of body extensions – including Trunk 1967–9 (Tate T07855), Arm Extensions 1968 (Tate T07857), and Scratching Both Walls at Once 1974–5 (Tate T07846) – in which unwieldy prosthetics are used to emphasise the fragility and vulnerability of the human body. For Unicorn, however, the layers of meaning are more complex: the single woman clad in white, the original forest location and the symbolism of the unicorn reflect what curator Germano Celant has identified as Horn’s ‘intentional manifestation of white magic, in which woman tries to win out over reality and society’ (quoted in Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum 1993, p.44).

Emerging onto the art scene in the late 1960s, the German artist Rebecca Horn was part of a generation of artists whose work challenged the institutions, forces and structures that governed not only the art world but society at large. In art, this meant a renewed critical focus on the human body, contesting the commodification of art objects by foregrounding the individual. This focus on the human body took on a particular personal resonance for Horn, who was confined to hospitals and sanatoria for much of her early twenties after suffering from severe lung poisoning while working unprotected with polyester and fibreglass at Hamburg’s Academy of the Arts.

Horn has made work in a variety of media throughout her career, from drawing to installation, writing to filmmaking. Yet it is with her sculptural constructions for the body that she has undertaken the most systematic investigation of individual subjectivity. Her bodily extensions, for example, draw attention to the human need for interaction and control while also pointing to the futility of ambitions to overcome natural limitations. Similarly, her constructions, despite their medical imagery, are deliberately clumsy and functionless, while other works attest to the unacknowledged affinities between humans, animals and machines.

Further reading

Ida Gianelli (ed.), Rebecca Horn: Diving through Buster’s Bedroom, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles 1990, pp.38–9.

Germano Celant, Nancy Spector, Giuliana Bruno and others, Rebecca Horn, exhibition catalogue, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 1993, no.4.

Armin Zweite, Katharina Schmidt, Doris von Drathen and others, Rebecca Horn: Drawings, Sculptures, Installations, Films 1964–2006, Ostfildern 2006, pl.25.

Lucy Watling, August 2012″

[credit]

«Berlin Exercises in Nine Pieces» Exercise 1: Scratching Both Walls at Once, 1974 – 1975

Rebecca Horn (1944-) uses the «Finger Gloves» object to measure the dimensions of an interior space. The scratching of the body extensions is audible.

“Between 1968 and 1972, German artist Rebecca Horn created a series of performances titled “Personal Art.” Not unlike Joseph Beuys, an artist with whom she readily claims affinity, Horn ascribes the genesis of this work to a single near-death experience. As a young sculptor in the 1960s, Horn, like many artists of her generation, worked with fiberglass and polyester. Unaware of the toxicity of these materials, the artist suffered severe lung damage followed by a long period of convalescence. Limited to drawing in her hospital bed, Horn sketched images of the human body and designs for wearable sculptures, or “body extensions.” She then sewed and constructed these, tailoring them to exactly fit her measurements and those of her friends and collaborators. Made of cloth, wood, bandages, belts, feathers, and found objects, Horn’s masks and extensions contain, constrain, and/or elongate the bodies of their wearers. To this day, Horn can be said to continually build upon this oeuvre. She is known to return to earlier objects and performances by citing or even reworking them. “My works are stations in a transformative process,” she has said. A “development that is never really finished.”1

…

Conceived as dialogues between Horn’s body and the space, Berlin-Exercises revisits themes explored in “Performances II.” In Scratching Both Walls at Once the dimensions of Horn’s Finger Gloves are extended further. Keyed to the width of her studio, Horn slowly scratches the tips of these even longer gloves along the walls to either side.” [credit]

Fabric, wood and metal Object, each: 70 × 1735 × 45 mm; Credit

“WATERSHED LINE

From May to September 2021

Kate is Artist-in-Residence in the Elan Valley.

The 1892 Water Act allowed Birmingham Corporation to purchase the watershed of rivers Elan and Claerwen. These 70 square miles would provide water to fuel the city’s industrial growth.

The WATERSHED LINE, the perimeter of the land claimed, was, and still is, marked by concrete posts.

https://www.elanvalley.org.uk/about/elan-links

Today, 81% of the Elan Estate is an Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). Ironically, the economic value of its water has protected it from the use of pesticides and other chemicals, preserving habitats for now rare plants and animals. However, harnessing the natural cycle of these valleys was a feat of Victorian engineering that accelerated industrialization, contributing to the current global environmental crisis.

As a ‘post-industrial’ pilgrimage in a ‘wild’ landscape, my walk from POST TO POST is a conversation about the complexities of the human footprint.” [credit]

This work has multiple sections: déambulation, where the artist silently walks across the screen carrying two bags wearing a white dress; Expansion, where the artist walks up stairs and across the screen – the image is doubled and reflected with reduced opacity and there is piano music playing; Transcription, where the artist walks across the screen in a white dress with a piece of chalk drawing a hip-height line across a black wall, then erases the lines with water – again the image is doubled during the drawing, but not the erasing, and music is present for the erasure.

“My work exists within an intermediary zone, a sort of matter space of a frontier I have produced and that I situate within the countries of France and the Democratic Republic of Congo. I am a cultural hybrid endowed with a composite identity. The plurality of my parents provide me with the authorization to interrogate my own history and that of a nation, the place of my birth, as well as the continent of Africa at large. The relationship that I maintain with my own personal history or histories and to history as a larger entity permits me to formulate a critical acquisition to write the concept of exitism. Exitism is a representation that is largely shared with history and even with practices at times. As the material of my work is always simple. I use historical facts that I interpret through the prediction of scene. Through these frontal images I expose my body that I use as a metaphor for the relationship between the human being and the world at large. My work sets up a direct relationship that centered on the world the field of society and politics. – Excerpts from Global Feminisms: Michèle Magema 2010″ [credit]

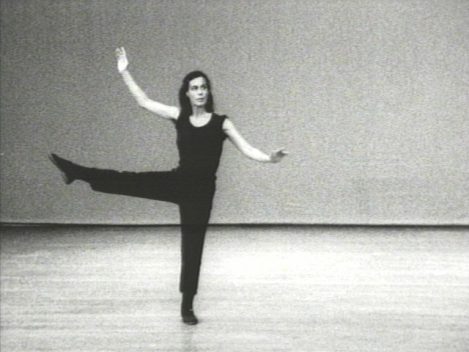

Yvonne Rainer, “Trio A” 1978. Video (black and white, sound), 10:21 min

“Yvonne Rainer—regarded as a foundational force in American contemporary art, film, and postmodern dance—began her career in New York in 1956. After a false start in acting, she entered the Martha Graham School, a dance school and associated company named for its founder, who is largely credited with revolutionizing modern dance. There, Rainer discovered a passion for this art form. She was trained in a style of movement characterized by expressiveness and virtuosity and in narrative choreography filled with drama and psychological intensity. But Rainer grew dissatisfied with the conventions of modern dance and the traditional relationship between dancer and audience. As she has explained: “Early on, I began to question the pleasure I took in being looked at, this dual voyeuristic, exhibitionistic relation of dancer to audience.”1 Fueled by such questioning, and her opposition to the tenets of classical and modern dance, she created Trio A.

Rainer choreographed Trio A in 1966, and performed it for the camera in 1978. Written for a solo performer, it incorporates no music and features a seamless flow of everyday movements like toe tapping, walking, and kneeling. “[It] would be about a kind of pacing where a pose is never struck,” the artist once described. “There would be no dramatic changes, like leaps. There was a kind of folky step that had a rhythm to it, and I worked a long time to get the syncopation out of it.”2 Trio A positioned Rainer as a leader among the dancers, composers, and visual artists who were involved in the Judson Dance Theater (which she co-founded in 1962), an avant-garde collaborative that ushered in an era of contemporary dance through stripped-down choreography and casual and spontaneous performances.

Yvonne Rainer’s “No Manifesto”

A year before creating Trio A, Yvonne Rainer wrote her “No Manifesto” (1965). Through it, she declared her opposition to the dominant forms of dance of the period—typified by Martha Graham—and outlined the tenets of her radical new approach:

No to spectacle.

No to virtuosity.

No to transformations and magic and make-believe.

No to the glamour and transcendency of the star image.

No to the heroic.

No to the anti-heroic.

No to trash imagery.

No to involvement of performer or spectator.

No to style.

No to camp.

No to seduction of spectator by the wiles of the performer.

No to eccentricity.

No to moving or being moved.3

Early Recognition—a Double-Edged Sword?

Sometimes, artists find that groundbreaking work produced early in their career may overshadow the rest of their output. This was the case for Rainer with Trio A and “No Manifesto.” In her words: “It’s a little unfortunate, because it eclipses everything else I’ve done. [It’s] the most out-there, visible signature of my career. That and the ‘No Manifesto.’”4 In the 1970s, she stopped dancing altogether and turned her attention fully to filmmaking, producing films including Lives of Performers (1972), Kristina Talking Pictures (1976), and Privilege (1990). It was not until the 2000s that Rainer would return to choreography.” [credit]

“Shiraga’s artistic legacy is rooted in post-war Japan when people were full of energy and there was excitement in the air pushing to try new things. This aspirational spirit, which reined in the society, led to the appearance of new art movements including one of the most famous and highly acclaimed groups, Gutai, of which Shiraga became one of the most renowned representatives.

Gutai Art Association, the first radical, post-war artistic group in Japan was founded in 1954 in Osaka under the leadership of Jiro Yoshihara. Yoshihara’s motto was simply to do what no one had done before and not to imitate others. The group’s artists that went on to great renown, like Saburo Murakami, Sadamasa Motonaga and, of course, Shiraga fully embraced the free spirit of the art and raw, concrete (Gutai in Japanese) creativity. However hardly anyone in the movement embodied Gutai’s philosophy more dramatically than Shiraga, who developed a unique technique of pouring paint on the canvas and creating brushstrokes with his feet by swinging on a rope hung from the ceiling.

Shiraga was born in Amagasaki, Hyogo Prefecture, in 1924 into the family of a kimono business owner. From early childhood due to his background he had access to the marvels of traditional Japanese art: calligraphy and antiques, classical theatre and cinema, ukiyo-e prints and ancient Chinese literature. After studying traditional Japanese painting in Kyoto, Shiraga fulfilled his long desire to explore Western paintings. He moved away from the figurative style and pursued a more emotional direction. As a result, in the early 1950s his work arrived at total abstraction following closely the mood of the times – to challenge conventional artistic forms. The Tokyo retrospective opens with a selection of Shiraga’s unfamiliar abstract works from this period dating as early as 1949 when the artist was only 25 years old.

Around 1952, Shiraga together with artists Murakami and Akira Kanayama formed the Zero Society (Zero-kai) relying on the idea that art should be created from the point of nothing. Shiraga started experimenting with fingers using them to make distinctive patterns, as shown in a couple of works on view. The finger technique eventually led him to placing the canvas flat to avoid the paint dripping. It made reaching the canvas center impossible unless the artist would step on it. And so he did. In summer 1954 the legendary Shiraga’s foot paintings (otherwise sometimes referred to as action paintings, the term originally coined for Jackson Pollock’s works) were born and the same year the artist joined the Gutai movement. The primordial energy of these new foot works explored tension as well as the sense of power. Sliding on the canvas Shiraga used his physical strength to reach a certain state between conscious and unconscious reducing his painting approach to a performance. It was a visual record, a memory of a specific action at a particular moment in time. Shiraga wouldn’t stop exploring the possibilities of a painting practice that would document his canvas exercises.” [credit]

Live Performance by Kubra Khademi

16 Feburary 2016, Paris, France

“PE: When you moved to France, you continued to put on walking performances. For Kubra & Pedestrian Sign (2016) you walked through Paris in a black dress and high heels with a pedestrian crossing lightbox tied to the top of your head, except the green sign in the box was a female figure. I’m curious about how you found the experience of reclaiming public space in this new European context.

KK: The challenges are different here: the texture and sense of the landscape, the cityscape, the people around me. Public space in France and the Parisian art scene are still very masculine, but in a far more subtle and sophisticated way. No one harasses me in Europe like they do in Afghanistan. I don’t need an armor to walk here. The city is like that blank white page again. That was the first performance I put on in a public space after then one in the Kabul. It was a few months after I arrived. The image of me is almost funny. I was looking into people’s eyes and allowing them to talk to me. Most of the reactions were similar, but one woman screamed at me from the other side of the street, “That is sexist! Skirts are sexist!”” [credit]