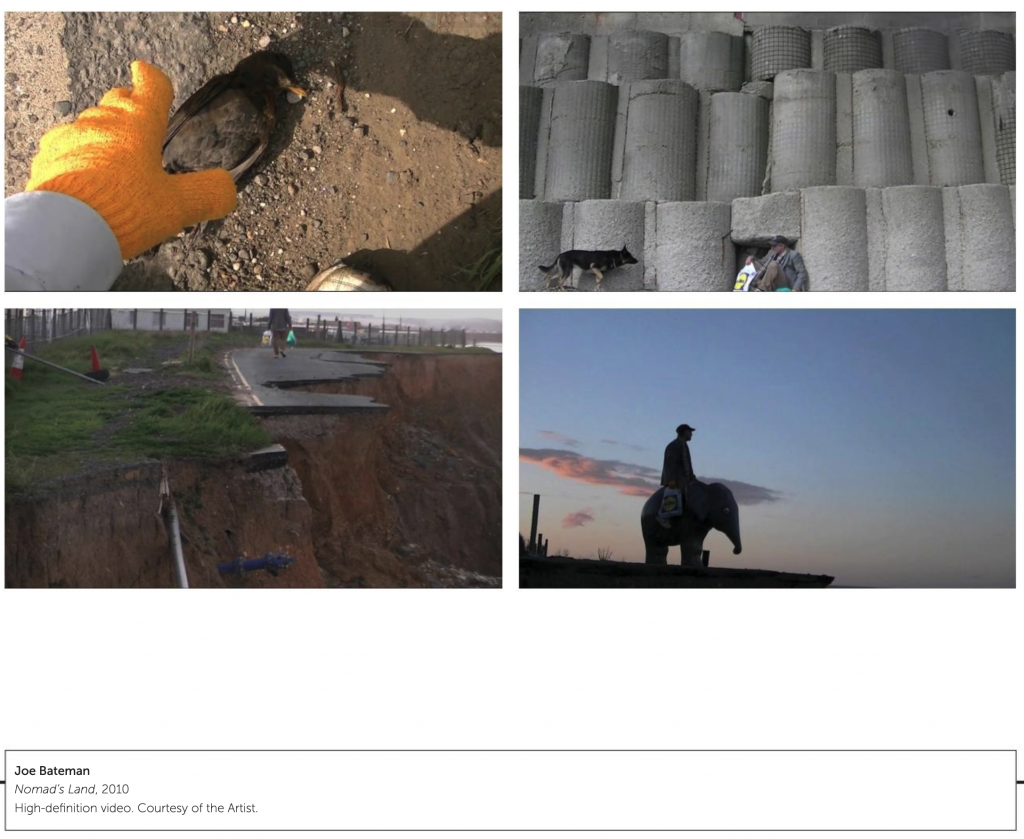

- Kubra Khademi, Armor (2015)

- Kubra Khademi, Armor (2015)

- Kubra Khademi, Armor (2015)

- Kubra Khademi, Armor (2015)

Images screen captured from video documentation

“Since 2015, the Afghan artist Kubra Khademi has been based in Paris. Khademi moved to France due to the violence she faced in the wake of her 2015 performance Armor, for which she walked through a busy area in central Kabul dressed in custom-made metal armor: an artistic gesture meant to highlight how women are sexually and verbally harassed in public spaces. After studying fine arts at the University of Kabul, and later at the University of Beaconhouse in Lahore, Khademi committed herself to the continuous reflection of the condition of women’s lives in Afghanistan. Her work spans performance, painting, and drawing. In the last year, Khademi finished a series of large-scale paintings and drawings. They are inspired by the way Afghan women express their sexuality through a coded and subversive poetic language that remains unrecognizable to men. The art critic and editor Philomena Epps met Khademi for V/A and spoke to her about the assertive and unapologetic presence of women in her work as a form of resistance against the patriarchal order. Their conversation is published here as a contribution to our current thematic focus “disappearing.”

PHILOMENA EPPS: I wanted to begin our conversation with the concept of “disappearing.” I’m thinking about how your work might be framed as the antithesis to this theme, because it insists on the presence of women. There is an insistence on the body, on being seen, and a profound emphasis on the female subjectivity, all as a form of resistance. Could you, as an artist and as a woman, speak about this refusal to disappear in relation to physical presence as a political act?

KUBRA KHADEMI: Much of my work comes from my personal life experience and stories about the women I know. I talk about them; I talk about myself, about my mother, about my sisters. Someone once asked me, “Where are the men in your family?” This question was asked out of curiosity, but I received it very violently; I was disturbed. I thought, “Why are you repeating what my society, where women don’t exist, has done to me? Why should I reproduce what it has done?” My work is becoming more and more feminine. These stories can’t be told another way. It’s all about liberty; it’s about saying whatever I want to say.

PE: Your artistic practice has been engaged with the condition of women’s lives and questions of violence and repression. Both issues are historical as well as deeply personal to you.

KK It reflects the heart of popular Afghan society: the men are outside, and the women have to be in the kitchen. Women have to serve the soldiers; they have to cook for them. That is how they get their value. Religion plays a big role in serving the patriarchy, or perhaps it is patriarchy that serves religion. And women also practice patriarchy. People tell me that men are also imprisoned by patriarchy, that it is also violent to men, that it tells them they should not be soft, they should not be feminine – of course, but I don’t care. I have five sisters and four brothers. When my father died, my brother took over. If it wasn’t him, it would have been another man: an uncle, a neighbor. This isn’t a theoretical argument – it all comes from my life experience. I’ve grown up in a culture and society where being an artist and a woman is a terrible thing, because art is all about self-expression. When I was a child, my mother took us to bathe in a public, woman-only hammam. It was a very secure and trusting environment; I saw so many free, female bodies. It was there that I saw the adult female sex for the first time. I didn’t understand what I was feeling, but when I got home, I was looking for paper. I was already drawing a lot then, so I took my sketchbook and started drawing what I had just seen: all these female figures. I then hid my drawings. I tore them up and hid them under a carpet because I had this fear. My mum was cleaning and found the drawings a few days later. I was so scared. She got the electric fire and hit me with it. I’ve forgotten the pain of it, but I haven’t forgotten the feeling of guilt she gave me. I hung my head in shame for months; I could not raise it. My mum didn’t buy sketchbooks for me again, and I didn’t draw for a long time. Paper was very expensive anyway. When I draw today and leave expanses of white space, it is such a celebration for me, that I can buy these big sheets of white paper. I draw sexually liberated women, and I also practice leaving all this white space that I wasn’t afforded when I was a child.

PE: It’s interesting that your primal instinct was to record what you were seeing, even when you were so young, because this formative moment ended up shaping the direction of your work as an artist.

KK: I am so happy that there is no guilt anymore. We have to celebrate living without any guilt. The guilt was more painful than that electric fire on my body. I remember so clearly how my head was down for months, the feeling of pain in my neck. I was paralyzed. I could not draw.

PE: The physical toll shame takes on the body is unsettlingly overwhelming.

KK: No one spoke about it. When I came to France in 2015, after twenty-six years, I started talking about these experiences. I tried to re-draw that image from the hammam. I won’t forget it. I put colour on their bodies, and I called it Twenty Years of Sin. When people see that drawing, they do not fully understand what it means to me, neither back then nor now.

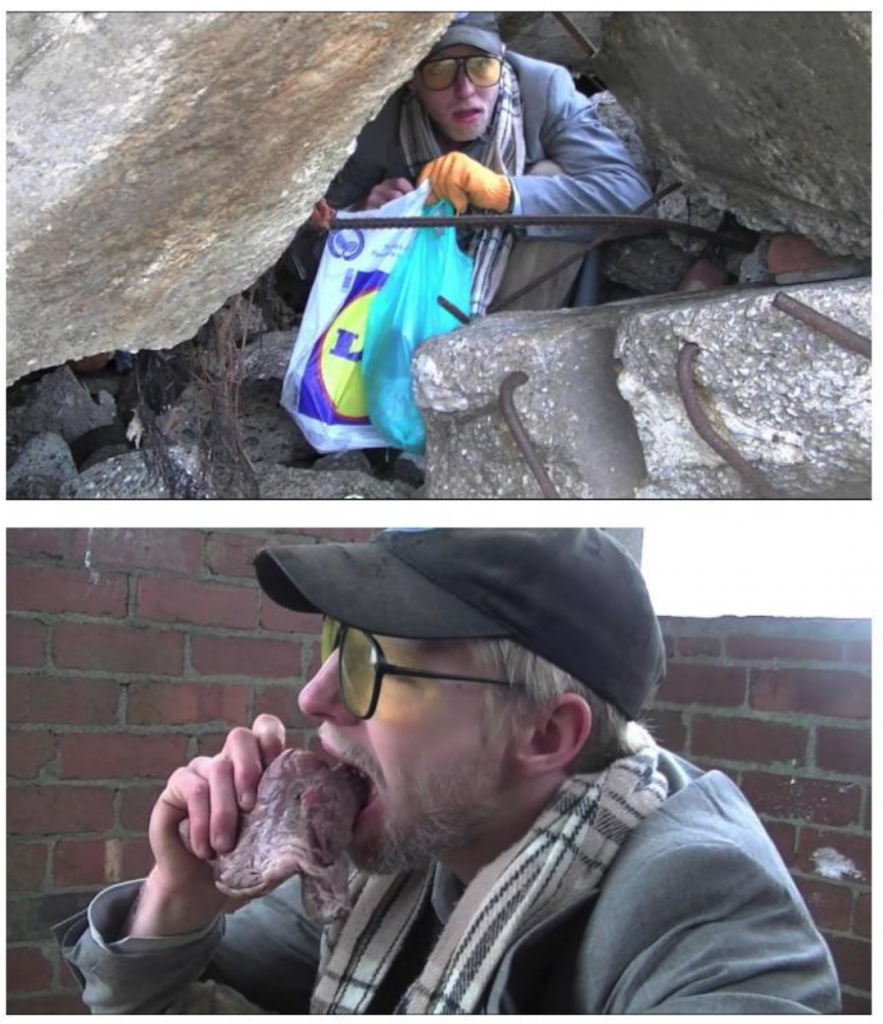

PE: I’d like to go back to 2015, to the performance piece Armor that led to you moving to France: you walked through a street in central Kabul, a public place in which you were highly visible, dressed in custom-made metal armor that emphasized your breasts, belly, and bottom. You had made it in response to the violent patriarchal politics of Afghanistan, particularly to how women are sexually assaulted and harassed in public spaces. Could you say more about what motivated the development of that performance, but also how the impact and severity of the performance’s fallout ended with you fleeing the country.

KK: I’m an artist who finds public space very inspiring. It’s fluid and free, the world as my studio. Before Armor, that was how I was working in Afghanistan. But I also come from a world where I should not be present. I have been sexually harassed like millions of other women in Afghanistan. We live in a culture of systemic sexual violence. If you’re raped, it’s your fault. It’s your destiny because you’re a girl. It’s taboo to bring this up. Very few women feel able to talk about it. I find that so disturbing. While I was performing Armor, the number of men around me increased every few seconds. I felt fear but also assured. That was what the performance was about: this is the way it is. I was prepared to be mocked, insulted, laughed at – those are daily things we experience as working, active women. That’s everywhere; I was ready for that. However, my performance was not an image that people saw daily. After I arrived at the end point, where my friend was waiting for me in a taxi, people started jumping on the car. The driver was frightened because he was in danger, so he started driving without looking back. When I turned on my phone the next day, I saw that it was all over the news and social media. My image was shaking the country. I assumed that it soon would be forgotten, but that was naive. It didn’t die down. The performance was presented as a project of the United States against Islam values, as blasphemy, as encouraging female prostitution. The image then started circulating internationally, which made it worse because people in the Western world admired it. It was out of control. The world was in shock; my country was in shock. Once again, local media spoke about it, as I was being criticized for being a spy and a puppet of the United States that wanted to gain the attention of the West. And outsiders perceived my work as activism. That was painful for me. This wasn’t activism; I’m an artist. By the time I moved to France, I was in significant danger. I was lucky I stayed alive. To this day, I still receive messages of hate on Instagram from Afghan people.

PE: I see it as an artistic work. The suit of armor, the costume of war, creates a striking image of protection and aggression, but it is contrasted with this enhancement of the female form, exaggerating the softness and vulnerability of the unclothed body. The act of walking is also reminiscent of female artists who used their body as artistic material in the 1970s. I’m thinking about performances and images made by women such as Valie EXPORT, Marina Abramović, Anna Maria Maiolino. These artists developed revolutionary ways to speak about violence against women, about censorship, or harassment, through a performative language and by provocatively staging feminine vulnerability and endurance in the act of spectacle. Seeing your performance only as a protest piece minimizes the depth of these artistic considerations and intentions. Of course, there are gestures within the work which could be thought of as activism, but it is art.

KK: Seeing it as an activist project implies judgement. It is an art piece. When I was a child, I already used to say, “I am an artist.” That is unbearable for my society. My society wanted to imprison me, make me a wife, a mother, but I wanted freedom. I am unmarried. I do not care about it.

PE: When you moved to France, you continued to put on walking performances. For Kubra & Pedestrian Sign (2016) you walked through Paris in a black dress and high heels with a pedestrian crossing lightbox tied to the top of your head, except the green sign in the box was a female figure. I’m curious about how you found the experience of reclaiming public space in this new European context.

KK: The challenges are different here: the texture and sense of the landscape, the cityscape, the people around me. Public space in France and the Parisian art scene are still very masculine, but in a far more subtle and sophisticated way. No one harasses me in Europe like they do in Afghanistan. I don’t need an armor to walk here. The city is like that blank white page again. That was the first performance I put on in a public space after then one in the Kabul. It was a few months after I arrived. The image of me is almost funny. I was looking into people’s eyes and allowing them to talk to me. Most of the reactions were similar, but one woman screamed at me from the other side of the street, “That is sexist! Skirts are sexist!”

PE: Earlier this year, Galerie Eric Mouchet in Paris presented your solo exhibition From the Two Page Book. The gouache paintings depict a matriarchal society, in which nude women engage in sexual and vulgar acts. I’d like to ask you about the erotic dimension of these paintings. The series draws on the writings of the poet Rumi in a homage to the particular form of language that Afghan women use when they discuss their sexuality.

KK: I have a clear position toward the women in my drawings. This is how I show femininity. These women in my paintings are not nude. To me, they are not naked; they are just bodies. If I was to clothe them, then in what clothes? Which identity? Do I dress them in the clothes I wore in Afghanistan or the European style I wear now? Clothes are dictated by geographical and religious borders. When I was a child, I drew what I saw, and I still see women this way. I chose Rumi to set up a parallel with the dialogue between women I know. All of these drawings come from a feminine universe that exists within Afghan popular culture. It’s fascinating how religion has divided women and men into two specific spaces. What women have constructed in their own space is another world that is poetic and liberated, where they trust one another. Men occupy space in a very brutal way. With my mother and her friends, when they come to talk about things, they are constantly laughing. This doesn’t mean they are happy or naive. They talk a lot about sexuality. If you were to arrive in an Afghan village, you would think, “Oh my god, the women are so repressed here,” but you would be wrong to think they don’t know anything about their sexuality. It comes out in another very beautiful way. We talk about fetishes and sexual fantasies, but it is not rooted in pornography. We talk about sex in a very funny way. When women talk about their sexual experiences, which they do woman to woman, they do not name their husbands. A friend of my mother’s calls her husband “a donkey,” which both mocks him and raises his sexual power. We use a lot of metaphors. This humor is so present in our society, but it is invisible to men. In my paintings, the body of the donkey has been removed, leaving only his sex. We say, “Cut it and keep it under the bed so it can serve you whenever you want,” because we do not want anything else. Men are just useless creatures.

PE: It’s like another dialogue or even a code. Your painted images are another manifestation of this coded language in visual form.

KK: Yes, it’s all about code. When I showed these works to my sister and my mother, we all knew what they were about. It wasn’t anything new. These are daily conversations. It’s fluid among us, we practice it. It was necessary for me to create a feminine universe. There is one work called Frontline (2021): women end up on the frontline very easily. One woman is pregnant, the other woman next to her is shitting. Women are called dirty, yet they have to be pure. The choice of being pregnant doesn’t exist in Afghan culture. I’m navigating between all of these issues. It’s a fight against the history and a system protected by religion. All the images are deliberately huge. These women have to be bigger than men. They are all two meters, and the drawing itself is 6 meters by 2.5 meters.

PE: They dominate the space. They are larger than life. This month, as part of The Enchanted exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris and an offshoot of the events programmed by Nuit Blanche, you will destroy a series of recent drawings in a public performance. Titled Power and Destruction, these images depict sexually liberated warrior goddesses.

KK: Last year, I made a lot of drawings. It was fascinating to express myself in this way. The medium allows for exploration and imagination. You can create another world, unlike performing in front of the camera. I wanted the drawings to mirror live performance art, and the way it disappears after the event. I also decided to take the power back regarding the destination of my work. I have drawn mythical goddesses inspired by my Afghan origins. They are all extraordinary women. I want to exert my power as an artist as both the creator and destructor of these works. The only person to remain is the artist, who is alive.” [credit]