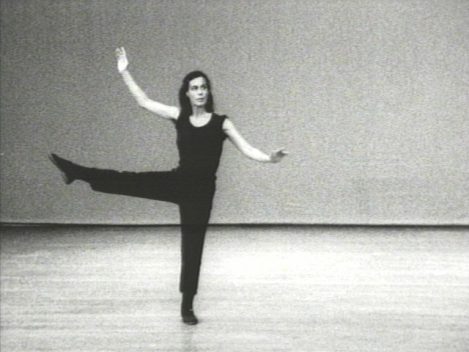

Yvonne Rainer, “Trio A” 1978. Video (black and white, sound), 10:21 min

“Yvonne Rainer—regarded as a foundational force in American contemporary art, film, and postmodern dance—began her career in New York in 1956. After a false start in acting, she entered the Martha Graham School, a dance school and associated company named for its founder, who is largely credited with revolutionizing modern dance. There, Rainer discovered a passion for this art form. She was trained in a style of movement characterized by expressiveness and virtuosity and in narrative choreography filled with drama and psychological intensity. But Rainer grew dissatisfied with the conventions of modern dance and the traditional relationship between dancer and audience. As she has explained: “Early on, I began to question the pleasure I took in being looked at, this dual voyeuristic, exhibitionistic relation of dancer to audience.”1 Fueled by such questioning, and her opposition to the tenets of classical and modern dance, she created Trio A.

Rainer choreographed Trio A in 1966, and performed it for the camera in 1978. Written for a solo performer, it incorporates no music and features a seamless flow of everyday movements like toe tapping, walking, and kneeling. “[It] would be about a kind of pacing where a pose is never struck,” the artist once described. “There would be no dramatic changes, like leaps. There was a kind of folky step that had a rhythm to it, and I worked a long time to get the syncopation out of it.”2 Trio A positioned Rainer as a leader among the dancers, composers, and visual artists who were involved in the Judson Dance Theater (which she co-founded in 1962), an avant-garde collaborative that ushered in an era of contemporary dance through stripped-down choreography and casual and spontaneous performances.

Yvonne Rainer’s “No Manifesto”

A year before creating Trio A, Yvonne Rainer wrote her “No Manifesto” (1965). Through it, she declared her opposition to the dominant forms of dance of the period—typified by Martha Graham—and outlined the tenets of her radical new approach:

No to spectacle.

No to virtuosity.

No to transformations and magic and make-believe.

No to the glamour and transcendency of the star image.

No to the heroic.

No to the anti-heroic.

No to trash imagery.

No to involvement of performer or spectator.

No to style.

No to camp.

No to seduction of spectator by the wiles of the performer.

No to eccentricity.

No to moving or being moved.3

Early Recognition—a Double-Edged Sword?

Sometimes, artists find that groundbreaking work produced early in their career may overshadow the rest of their output. This was the case for Rainer with Trio A and “No Manifesto.” In her words: “It’s a little unfortunate, because it eclipses everything else I’ve done. [It’s] the most out-there, visible signature of my career. That and the ‘No Manifesto.’”4 In the 1970s, she stopped dancing altogether and turned her attention fully to filmmaking, producing films including Lives of Performers (1972), Kristina Talking Pictures (1976), and Privilege (1990). It was not until the 2000s that Rainer would return to choreography.” [credit]