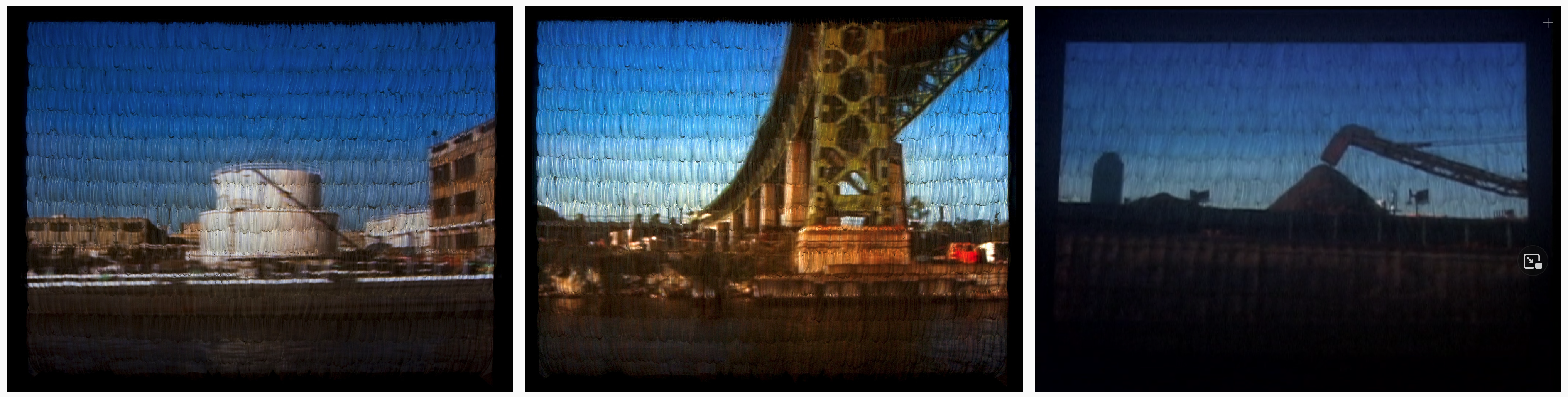

Credit: http://www.moira670.com/#/fissures-holes-limbs/

“Fissures, Holes, Limbs: breathing dislocated scales is an eco somatic sound walk centering disability.

I-Park Kicks off Seventh Art Biennale in East Haddam

BY CATE HEWITT, SEPTEMBER 23, 2019 ART & DESIGN

EAST HADDAM — At night, animals, birds, flowers, and even mushroom spores become active, moving about, making sounds and leaving traces, mostly unbeknownst to humans.

Participants in artist Moira Williams’ sound walk called “Fissures, Holes, Limbs: breathing dislocated scales,” were invited Sunday to shift from “daylight to moonlight” and experience night sounds and images she had recorded onsite at I-Park, an international artist-in-residence program founded in 2001.

Williams, a New-York-City-based artist, is one of nine artists in I-Park’s seventh Site-Responsive Art Biennale who spent three weeks on the program’s 450-acre campus “creating ephemeral artworks that respond to the property’s natural and built environments,” according to the program notes. The artists’ works can “take the form of environmental sculptures, videos, aural experiences or performance pieces.”

At the beginning of Williams’ sound walk, participants were asked to choose a stick from a number of precut tree branches, mostly about five or six feet in length. These branches were used as “limbs,” extensions of the human body, to explore holes and fissures in the path, as well as rocks and lichen.

After the band of sound walkers set off along a path, Williams stopped the group at a field and played a recording she had made while camping onsite of an owl hooting.

“Think of how the owl moves so quietly throughout the night and what it disturbs and what it accentuates, think of the different way our breath moves and accentuates as well, think of the spores and the seeds that we never see that we move,” she said.

She asked the group to face the field and to lift up their shoulders and think about them as wings, with the limb as an extension of sorts.

“Think about how they feel in the air and what you can move and what you can share and extend,” she said. “If you have a limb, an extra limb with you, please raise your limb in any way that you like, and think of your shoulders and your extra limb, think of the breeze going through your shoulders and your extra limb.”

Dressed in a white hazmat-type suit embellished with bright neon stripes made from tape, Williams carried a roll of black wire on one shoulder, like a techie epaulet, and a small speaker and projector connected to her mobile phone in a pouch around her waist. On her head was a wide “hat,” made from a piece of flat white painted cardboard with a space cut out for the top of her head, and long neon green streamers attached at each end that trailed behind her when she walked.

As the group proceeded down the path, Williams removed her hat and projected a tiny video of a fox she had recorded at night, letting the walkers experience the sight and sound as they hiked past.

She asked everyone with “an extra limb” to use it to touch the rocks, holes and lichen along the path, as a way to experience the site.

Soon the group came upon a field where Williams had created a labyrinth.

“Choose a path and walk to where you can find a white stump,” she instructed. “We’re under a full moon in the middle of the night, it’s an extraordinary full moon.”

Soon the group gathered around a white stump that had holes drilled in it about the size of the limb walking sticks. She asked those who had limbs to share them with those who were without.

“Those who haven’t had an extra limb, think of the limb that they now have and how the previous person used that limb and what that means to them not to have it now,” she said. “And think about whether the bark is smooth and whether there’s holes or fissures or lichen or even insects on your limb.”

Williams invited everyone holding a limb to place it in one of the holes in the stump, which created a kind of tree sculpture. The new tree symbolized connection, she said, and could forge a new identity for everyone who took part.

Credit: http://www.moira670.com/#/fissures-holes-limbs/

“If you walked with an extra limb and want to think about if you have a new name, you can say your new name out loud if you do have one, or if you can think of a new name that might incorporate an extended limb,” she told the group. “My new name would be Lichen.”

Of the 20 participants, names like Woody, Meadow, Shaggy, Hiawatha and Tripod emerged.

Then Williams directed the walkers’ attention to the far side of the meadow where a large tree with bare branches reached to the sky, a living reflection of the group’s tree made from limbs.

“Look at the tree in front of us and think about the tree behind us and the juncture of all of us connecting all of us,” she said.

Williams next led the group to a boardwalk that snaked through a marshy area with numerous streams flowing along the ground.

At one point she stepped out of the path and projected a video of mushrooms sporing onto a series of white vertical boards that were set in the marsh.

“This is an image of sporing mushrooms that only spore at night and these are things we seldom get to see,” she said. “They’re just ghostlike spores that we’re gathering on our own bodies and sharing with the rest of the world.”

Williams, who holds a BFA from the School of Visual Arts, a graduate certificate in “Spatial Politics,” and an MFA from Stony Brook University, said her underlying interest is about “making the environment accessible to all people, especially people with disabilities.

“It’s about thinking in ways that are not about independence but more about connectedness with the environment and one another,” she said. “It’s connectedness as a holistic ecosystem, we’re not just this very big myth about how we’re independent.”

She explained that her white outfit reflects a philosophy of healthcare — “the idea of nursing and empathy and being a caregiver.”

“I think of myself as a steward caregiver. I love wearing the white suit because I’m in the lead and I want people to see me,” she said. “The hat is a device to say, hey, here I am, come and join me, but it’s also the width of walkways that need to be for people that need a wheelchair.”

By walking through the marsh and the woods, participants will carry traces of the environment to new places, she said.

Near the end of the path, Williams crouched down, removed her hat and projected a time-lapse video of a lotus flower opening and closing at night on the pond at I-Park, a film she made while floating on the water.

The tour was over and she bade the group good-bye by saying, “Good morning everybody.””