Eduardo Navarro – Poema Volcánico – 2014

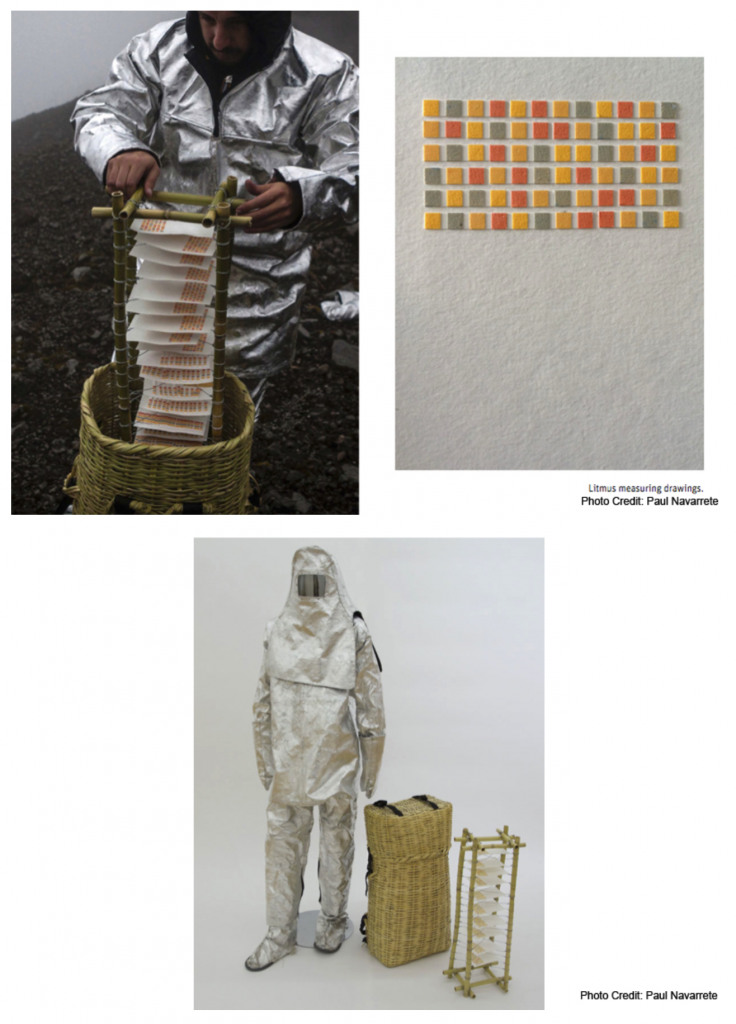

Poema Volcanico deals with the Ecuadorian volcanic geography. In 2014, while climbing the active volcano Guagua Pichincha, Eduardo Navarro created drawings from litmus paper, which measured the acidity of the gas emissions produced by the fumaroles inside the crater of the volcano. [credit]

“Eduardo Navarro lived in Ecuador between the ages of eight and twelve. During that time, Navarro would eat breakfast and dinner daily in front of a volcano, pondering it. The artist noted that as an adult, it meant a lot to him to return to the country to create a work of art that was both sentimental and a personal artistic challenge.

Leading up to the 12th Bienal de Cuenca, Navarro got the idea for his volcano-related artistic endeavor. He thought, “How can I work with the geography, landscape, and energy of the volcano?“ Instead of documenting a volcano (since we live in a world overly saturated with on-demand digital imagery), he wanted to create a project that would allow the volcano to express itself, and to do this, decided that he would have to enter it.

Navarro then got in contact with renowned Ecuadorian volcanologist Silvana Hidalgo of the Instituto Geofísico in Quito to confirm for certain which volcano it would be possible for him to enter without assuming the actual risk that it would erupt while he was inside. Through his extensive research and conversations with Silvana, Navarro decided to work with the Guagua Pichincha volcano.

Guagua Pichincha was known as one of the safer active volcanoes to trek into in Ecuador. To provide a comparison, Cotopaxi was another option, but Navarro explained that one had to be on the level of a professional mountain climber to enter its crater. Guagua Pichincha, on the other hand, was known in Ecuador as the “training mountain” that one would tackle before becoming a professional climber.” [credit]

Guagua Pichincha volcano

“Once Navarro decided upon the Guagua Pichincha, he had to figure out what his process would be leading up to the climb and artistic execution. After spending the required monthlong period adjusting to the proper oxygen level for the climb, Navarro decided to enter the crater twice, with two different guides (including record-setting climber Karl Egloff). His first trip would be to see what the crater was like, test expectations, and become familiar with the experience of going inside it. His second trip would be geared toward executing the artistic portion of the project.

On the first trip, Navarro realized first-hand how difficult it was to trek down into the crater and come back up, regardless of the intense physical prep work he made sure to do in advance. Also on the first trip, Navarro identified fumaroles (the cracks where smoke escapes from the volcano’s center) as the feature of the volcano he wanted to pursue working with artistically.

In regard to how he was going to work with fumaroles, one of Navarro’s first ideas was to get a woven basket, lower it down into the crater, and then try to pull it back up and see what would come out. Navarro thought that this could be an interesting idea, not only because baskets are accessible and would allow gases and sulfur to move freely through them, but because choosing woven baskets would give him the opportunity to work with an object that was native to Ecuador.

Navarro then had only a ten-day period between his two descents to figure out the details of both the device he was going to provide the volcano with so that it could express something, and the protective suit he was going to wear during the trek (most volcanologists wear fire protection and oxygen masks when entering craters). He went to the local fire department and asked if he could borrow a fireproof suit, and while the personnel there couldn’t provide him with one, they directed him to where he could get the materials so that he could make one of his own.

There is no question that Navarro’s descent into the crater was a high-risk undertaking. Navarro noted:

It is a sad thing when you pass the guards in the front (entrance) at Guagua Pichincha. A few weeks prior, three geologists went in. One almost died and two had to be rescued with a helicopter, so this was much more dangerous than going for a hike, having a picnic, taking a photograph, and climbing out.” [credit]

Eduardo Navarro – Poema Volcánico – 2014

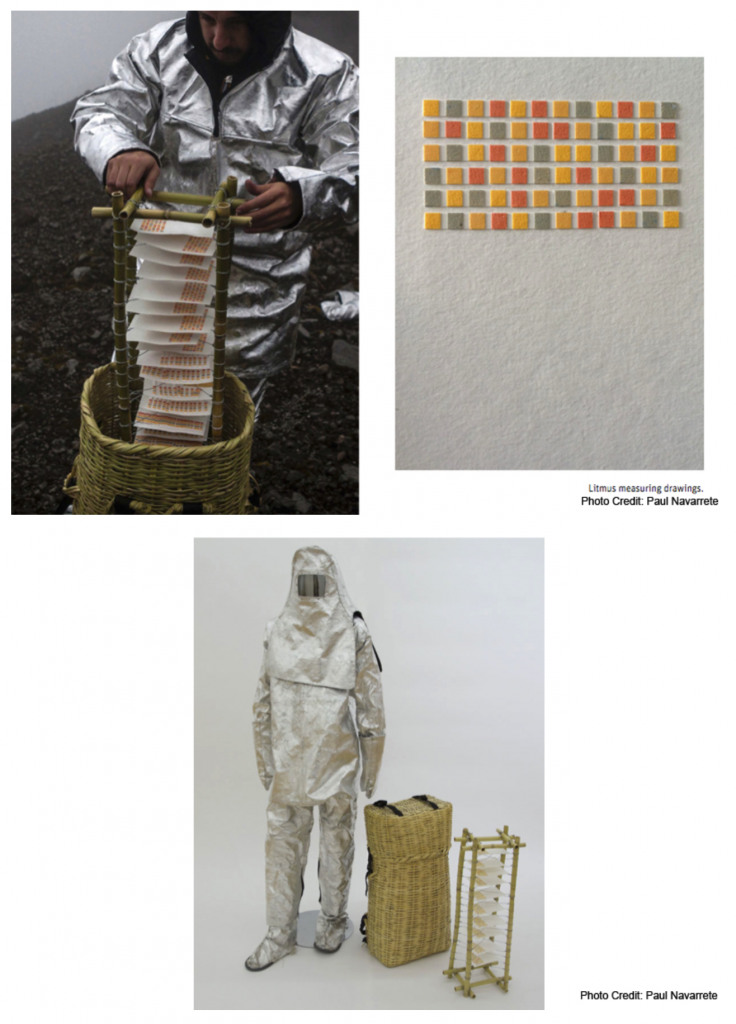

“Returning to the execution of his artistic endeavor, Navarro revisited the Instituto Geofísico to speak further with Silvana, who was crucial in the process. When Navarro raised the question, “How can I make the volcano draw?,” Silvana suggested the possibility of using litmus paper to react to the sulfur. Navarro immediately loved this idea, and started working with using litmus paper to create a machine that would allow the volcano’s energy to leave a trail. The result was a hand-made frame that acted as a rack for the sheets of litmus paper, which fit inside a custom woven basket that he worked closely with local artisans to create. Navarro wore the basket like a backpack during his trek, and eventually lowered it into the fumarole. He then left it down there for one hour, providing the volcano with a chance to leave its mark and express itself as if typing on a PH-reactive typewriter (example of result featured below – top right).

Ultimately Navarro titled this work Poema Volcánico because of the act of “handing the typewriter” over to the volcano. In other words, Navarro gave the volcano the power to express something that was not his interpretation of it.

To expand, it can be argued that Navarro gave true authorship to the volcano because he wasn’t attempting to control the project’s result. In fact, throughout the entire process, there was always the chance that the volcano and litmus paper wouldn’t have any real reaction at all. Even after months of preparation and two rigorous climbs, Navarro admitted that he was willing to accept any outcome. For Navarro, “it would have been fine if the volcano didn’t have anything to say.”

Setting himself apart from the many other talented artists who have been inspired by volcanoes throughout the centuries, Navarro’s intention was to transform the volcano from subject into artistic collaborator. Navarro does not claim that the volcano is necessarily the author of this work, nor that he himself is the author of this work. To Navarro, Poema Volcánico is about how well he and the volcano know each other.” [credit]

Eduardo Navarro – Poema Volcanico 2014