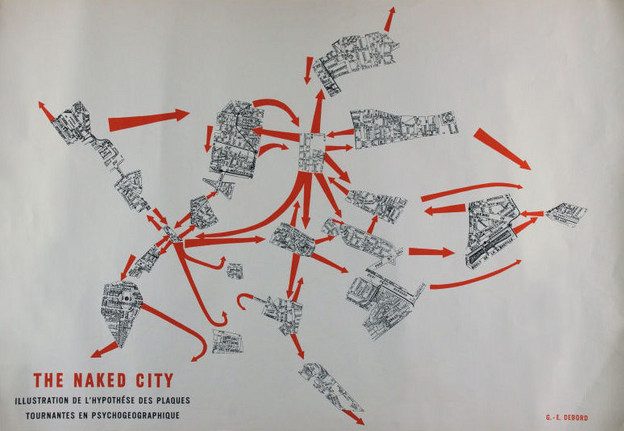

Guy Debord, The Naked City

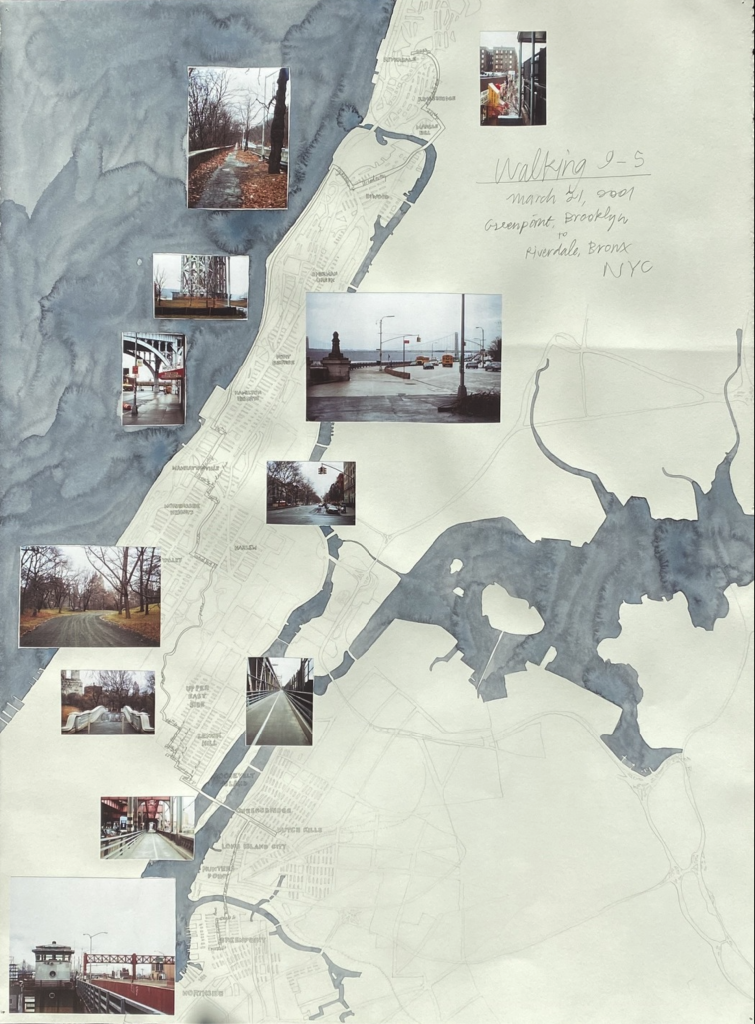

Guy Debord established the Situationist method of the dérive (drifting) as a playful technique for wandering through cities without the usual motives for movement (work or leisure activities), but instead the attractions of the terrain, with its “psycho-geographic” effects. (credit: Walk Ways catalog)

While similar to the flâneur, the dérive is influenced by urban studies (especially Henri Lefebvre). (credit: The Art of Walking: A Field Guide, 2012).

Read a more detailed account of the dérive from Debord’s “Theory of the Dérive,” first published in Internationale Situationniste #2 (Paris, December 1958): Debord-Theory_Of_The_Derive

Definition: Letting go of the usual reasons for walking – and being drawn by the affordances and attractions of the place.

The Drift or Dérive is one of the basic situationist practices advocated by Guy Debord and others. It’s a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiences. Dérives involve playful-constructive behaviour and an awareness of psychogeographical effects, and are thus quite different from the classic notions of journey or stroll.

Merlin Coverley mentions psychogeography has these core elements: [credit]

- the political aspect,

- a philosophy of opposition to the status quo,

- this idea of walking, of walking the city in particular,

- the idea of an urban movement,

- and the psychological component of how human behaviour is affected by place

Recently the idea of the drift has been extended in the practice of Mythogeography, where its characteristics are described thus:

-

- Best with groups of between three and six.

- There should be no destination, only a starting point and a time. A journey to change space, not march through it.

- To drift something has to be at stake – status, certainty, identity, sleep.

- In a drift, self must be in some kind of jeopardy.

- There may need to be a catapult: starting at an unusual time of day, taking a taxi ride blindfold asking to be dropped off at a spot with no signage, leaping onto the first bus or tram you see.

- There may be a theme: wormholes, micro-worlds, peripheral vision – whatever you want.

- Be tourists in your own town.

- Use the things around you as if they were dramatic texts, act them out.

- “…on a ‘drift’ we found ourselves at a Moto Service Station on the edge of the city. In the restaurant they had a guarantee printed on little cards. They’d give you your money back if you weren’t “completely satisfied” with your meal. So we organised to meet there on our next drift with about 10 other people; we ate big breakfasts and asked for our money back, because, philosophically, a cooked breakfast could never ‘completely satisfy’ a socially and culturally healthy person, not ‘completely satisfy’ all their desires and passions, not a human being. We got the money, but more importantly numerous staff were commandeered to interview us and we turned a restaurant into a debate about desire and fulfilment.”

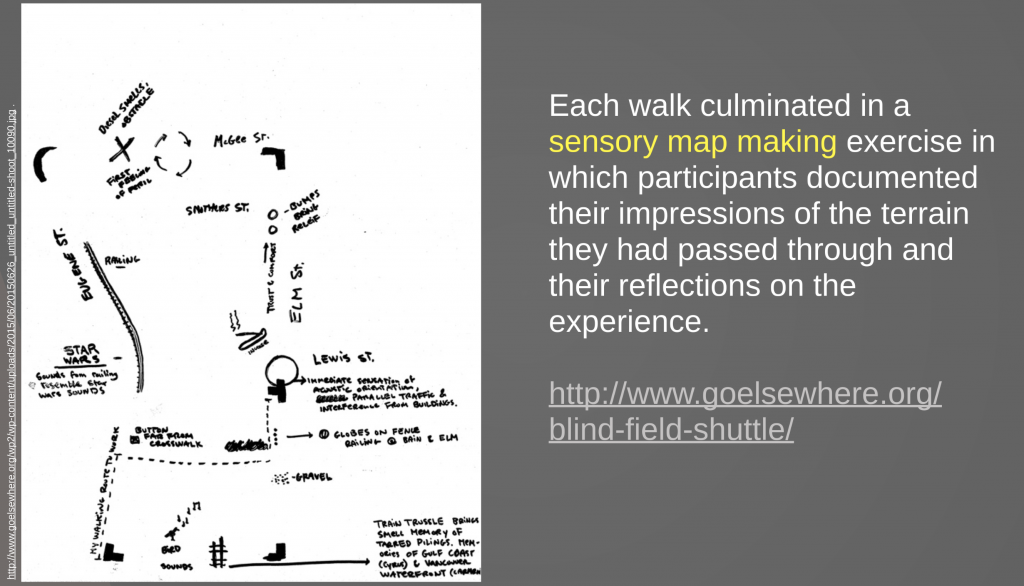

- The drift should be led by its periphery and guided by atmospheres not maps.

- A static drift: stay still and let the world drift to you.

- When you drift, use wrecked things you find to make new things (this is called détournement – using dead art and uncivil signs to create unfamiliar languages). Make situations: build miniature wooden villages, giant insects from branches, ritual doorways from burnt remnants, make a small model shed from the wood of a full-sized one and process it from shed to shed until you reach the sea. Construct things from what you find, enact imaginary searches, bogus investigations, gather testimonies for new religions. Just build!!! Leave stories, situations and constructions for any drifters that follow you, they’ll re-make them in their own ways.

Transcript of a Dérive

Credit to Jesse Bell, Notes on My Dunce Cap.

- Time/Place begun:

- Person/Persons a Party to the Initial Plan:

- Description of the Dérive’s Shape:

- Misunderstandings Created/ Discovered:

- Signed/Dated:

Occupy Oakland protesters (2011) Photo by Noah Berger, Oakland

Connections to 21st Century

“In addition to inspiring artists, architects and urban planners, the Situationist International’s take-back of public space is credited as catalyzing the The Occupy movement.

“We are not just inspired by what happened in the Arab Spring recently, we are students of the Situationist movement…One of the key guys was Guy Debord, who wrote The Society of the Spectacle. The idea is that if you have a very powerful meme … and the moment is ripe, then that is enough to ignite a revolution. This is the background that we come out of.” – Kalle Lasn, editor and co-founder of Adbusters, the group and magazine credited for Occupy Wall Street’s initial concept and publicity.” (credit)

Exercises:

Credits and references: