Alan Michelson (1953-, Mohawk) created a type of sculptural reenactment when he installed Earth’s Eye (1990) in lower Manhattan’s Collect Pond Park, outlining the now absent pond, a freshwater source that sustained Manhattan residents until tanneries polluted it and it had to be filled in during 1803. Forty cast concrete markers (22”x14”x6” each) referenced the natural and social history of the pond with low-relief imagery of plants and animals, and were arranged in the outline of the pond. Passersby walked around and within the installation, “bringing previous states of the locale into the here and now.” (Everett, Deborah. “Alan Michelson,” Sculpture, May 2007, Vol. 26 No. 4. Page 31.)

Category Archives: Reenactment or Reprise

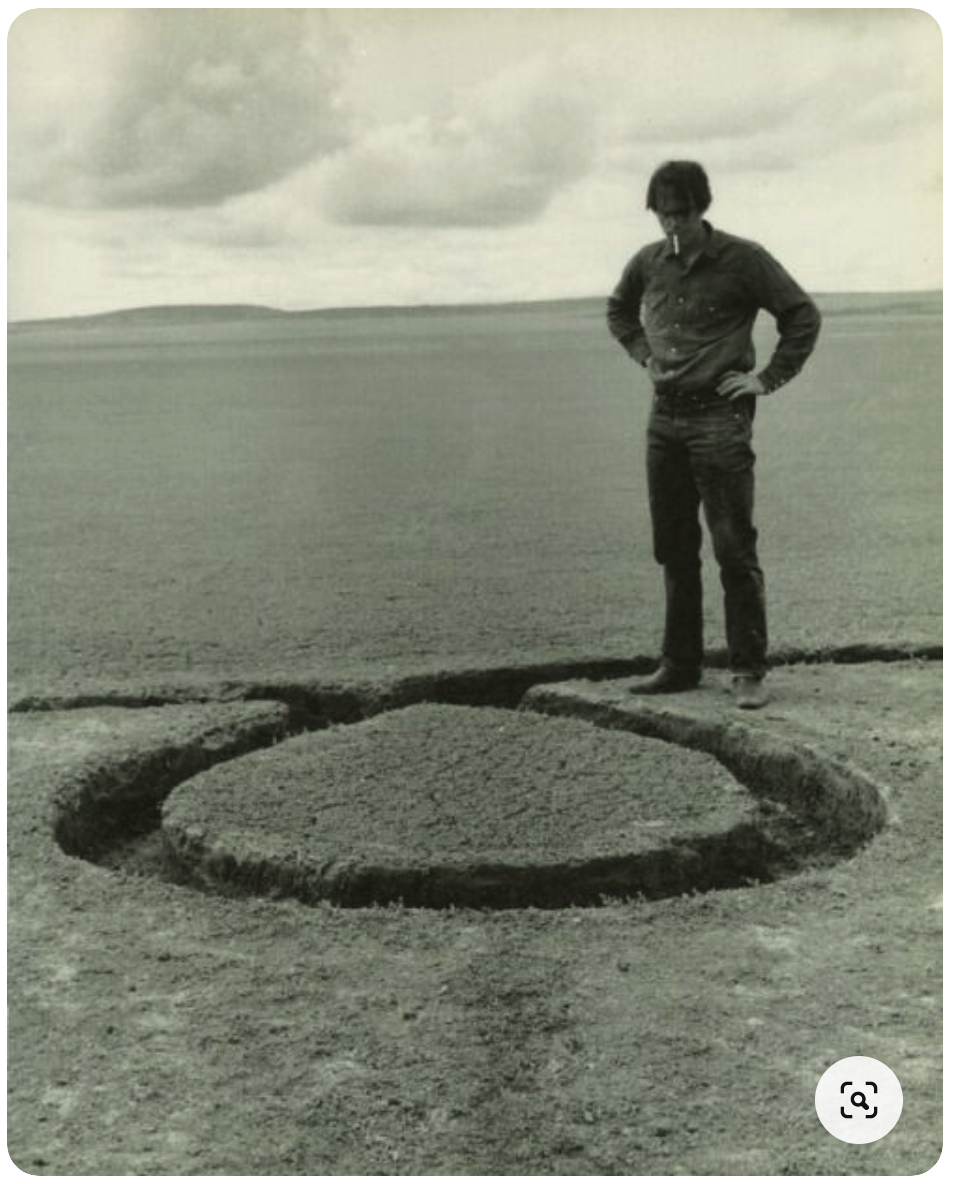

Michael Heizer, Isolated Mass / Circumflex (#2), (1968-1978)

Was installed outside the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas, United States.

Image 2: Photo: Tom Vinetz Image 3: Photo: Tom Vinetz

“The first version of this work was the ninth of the artist Michael Heizer’s “Nine Nevada Depressions” made around the state in 1968. This one is a circular loop made in a dry lake bed surface, at Massacre Dry Lake, near Vyo, Nevada. Six tons of earth was displaced, making a one foot wide trench, around 120 feet long, with the loop being 12 feet in diameter. Commissioned by Robert Scull. Apparently, no traces remain.” [credit]

TH&B, TH&B: Beachcombers (2016)

“Project Description:

In TH&B: Beachcombers, Hamilton collective TH&B (composed of artists Simon Frank, Dave Hind, Ivan Jurakic, and Tor Lukasik-Foss) stage an urban camping expedition at Ontario Place. In this durational performance, the group explores the West Island on foot and by canoe, producing an artwork that encompasses their process, their camp, and an installation built during their time there. A tongue-in-cheek response to narratives of wilderness exploration and discovery, TH&B: Beachcombers revels in the absurdity of scouring an artificial island, with the aim of collecting materials to create a rescue beacon. Referencing the 1970s kitsch exemplified by the Canadian TV show Beachcombers, TH&B’s performance combines industriousness, outdoor-savvy, and a healthy dose of humour.

Biography:

TH&B is the creative partnership of Simon Frank, Dave Hind, Ivan Jurakic and Tor Lukasik-Foss, a group of visual artists working out of Hamilton, Ontario. Resuscitating the moniker of the defunct railway that once serviced the Toronto, Hamilton and Buffalo rail corridor from 1895-1987 as a geographic marker, the team develops projects that response to site, context and history. Collaborating on all aspects of authorship and production TH&B investigates the intersection of rural, urban and industrial environments in the Great Lakes region.” [credit]

Dakota Commemorative Walk (2002-2012)

“They walked past red barns and white picket fences, past new housing developments and plowed fields dusted with snow. They walked with blisters on their feet and with hats pulled low to ward off the winter wind. They walked to remember.

The sixth annual Dakota Commemorative Walk ends Tuesday, Nov. 13, 2012 after six days retracing the footsteps of the 1,700 Dakota women and children who were forced to march 150 miles to Fort Snelling after the U.S. Dakota War of 1862.

Some call it Minnesota’s Trail of Tears.

“This is a ceremony,” said Gwen Westerman, who teaches humanities at Minnesota State Mankato and who has walked with the group since 2004. “It’s not a protest. It’s not a re-enactment. It’s a spiritual ceremony for healing and for honoring those women and children we descend from. We remember their strength and their determination.”

The first commemorative walk was organized in 2002, and organizers have held one every two years, leading up to this year, the 150th anniversary of the original march. After the Dakota War of 1862, the Dakota men who attacked government offices and white settlements were given cursory trials. Just more than 303 were condemned, and 38 were hanged in Mankato, remembered as a notorious event in Minnesota history.

After the war, 1,700 men, women, children, elders and mixed-race noncombatants were marched to a fenced camp along the river beneath Fort Snelling. During the winter of 1862-63 hundreds died of illness and exposure. In the spring, the remaining 1,300 were taken by steamboat and trains to a semiarid reservation at Crow Creek, S.D., where many more died of starvation and illness.

“They lived through three horrific experiences,” said Chris Mato Nunpa, a retired professor at Southwest Minnesota State University, who was bundled in a black coat and who talked as he walked along the shoulder of the road.

“They lived through this forced march, through the concentration camp, and through the forcible removal from Minnesota.”

He called their ordeal a genocide.

This year’s walkers set out just after dawn Wednesday from the parking lot of the Lower Sioux Agency in Morton, in the Minnesota River Valley. By Monday afternoon, the group had passed through the town of Jordan after covering about 20 miles a day. They walked on the shoulder of Scott County Hwy. 17, followed by a caravan of cars and vans carrying friends, supporters and elders too frail to make the journey on foot. Some people walk all six days; others join for a few days or even a few hours.

Each day, the procession is led by a woman carrying a sacred pipe wrapped in a blanket, surrounded by a quiet group. Farther back, people chat. The walkers stop and place a marker about every mile and honor two ancestors from the march.

At one stop Monday, a woman cleared weeds growing at the base of a tall electrical pole. She pounded a stake into the ground, topped with red and yellow ribbons. Someone called the names on the ribbon into the chilly wind: “Alek Graham. Maline Mumford.”

Then one by one, people went forward, took a pinch of tobacco from a leather pouch and sprinkled it over the stake.

“The name is not just a name. When we call their name, they come,” explained Nick Anderson, cultural chairperson for the Mendota Mdewakanton Dakota Community. “They are here with us.”

He said he walked as a way to thank his ancestors, one of whom was a sister of Chief Little Crow.

“When I think of what they had to endure, I don’t know if we can ever give enough thanks,” he said. “We survived, but we have lost a lot of our culture. Participating in this is a way for me to get some of that back.”

Other people came long distances to walk.

“The reason I’m here is because my great grandmother was on this march with her four kids and her mother,” said Reuben Kitto, who flew in for the march from Florida, where he spent 30 years working for Honeywell. Kitto spent his childhood on the Santee Sioux Reservation in Nebraska where many Minnesota Dakota were sent.

“This walk brings us back to the reality of how hard it was for them,” Kitto said. “The weather was a lot like this, there was a little bit of snow.”

“It’s a way for me to spend a day with my grandmother,” he said.

It’s also a way for him to spend time with his living family. His nephew Robert Thomas drove up from Winona to join the march for a day. Thomas is working on a commissioned play about the Dakota war and exile for the Minnesota History Theater and is concerned with helping both Dakota and non-Dakota remember the Dakota’s past.

“The old aunties and uncles are still passing down the stories,” he said. “The struggle is to get the younger generation interested.”

Kitto’s daughter, Ramona Kitto Stately of Shakopee, also was on the march, bundled in a long red coat and walking next to her father. Stately coordinates Indian education for the Osseo Area Schools and this year, as in past years, brought several students along on the walk.

As the sun started to dip low, she and others arrived at the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community center, where they would eat dinner together and reflect on that day’s walk.

“We carry a deep grief inside and if we don’t connect with that grief, we can’t heal,” Stately said.” [credit]

Dillon de Give, The Coyote Walks (2009-2017)

- Dillon de Give, The Coyote Walks (2009-2017)

- Dillon de Give, The Coyote Walks (2009-2017)

- Dillon de Give, The Coyote Walks (2009-2017)

“An annual walking project that illustrates a connection between New York City and the wild. It was originally performed to commemorate the spirit of “Hal”, a coyote who appeared in Central Park in 2006 and died shortly after being captured and re-released in the forest. The walk begins in the city and remains within sight of a coyote-like path for three days before ending in a relatively wild area. The Coyote Walk has run as an itinerancy, or walking residency since 2014.” [credit]

“It is collaborative research, a retreat (in an almost literal sense), or a mindful holiday. Prospective fellow walkers may share an interest in related subjects, such as urban planning, folk/visual/movement/social arts, biology or other natural sciences. Participants must be prepared for a strenuous walk (approx. 15 miles per day) and for sleeping outside. Please note, differently abled walkers are encouraged to be in touch.” [credit]

Additional images and writing www.coyotewalks.wordpress.com

“I grew up in the Southwest US (Santa Fe, NM— where coyotes are ever-present both as biological entities and as cultural signifiers). I witnessed this event in the media while living in New York City, and continued to think about it in the years following. I began to feel that a larger narrative was looming behind the topical debates. The incident threw the relationship of the city dweller and the natural world into relief. It wasnʼt an abstract suggestion of interconnection between the two; it was a (momentary) unmediated instance of collision– a moment of confusion for both. Hal disrupted a normal state of affairs by presenting himself as an embodiment of something external to our picture of daily life in an orderly civilization. In this he was as comedic as he was threatening. Was this a typical animal or an exceptional one? What was he thinking? And how, exactly, did he find his way into the city?

One way to try to understand this story was to guess about the geography of the journey. The most obvious geographic challenge is the channel of water that separates the island of Manhattan from the mainland of the Bronx– like a moat surrounding a castle. Adrian Benepe, the NYC Parks Commissioner at the time, publicly hypothesized that Hal crossed a small Amtrack trestle bridge over the Spuyten Duyvil Creek at the northern tip of the Manhattan. This became a prevailing theory, but not the only possible one. Other scenarios were equally possible. For example, if Hal had utilized the long Bronx River corridor as a path, he might have crossed over the Harlem River further south and east. Because there were few eyewitness accounts, no camera traps, and no DNA analysis done on Hal, the definite crossing location will remain unknown. This crossing is a big plot point of the story as presented in the media. It came to stand for the dramatic moment in which a cunning trickster privately transgressed from the natural world into the human world. Looking closely at possible routes however, it becomes clear that there were many such crossings.

The Coyote Walks are fueled by curiosity about what it would mean to cross over the line between “the city” and “nature” oneself, to literally connect the two places. The walks are guesses about how coyotes enter New York City that are made with reverse human journeys out of the city. The project began as a kind of memorial to the incident— walked around the anniversary of Hal’s death and initially called the “laH” journey, a backwards spelling of the name. The Coyote Walk is now a time to pose questions about urban life and nature, to learn from the experience of stepping away from the city, and to consider walking practices (human and animal) as imaginative acts.” [credit]

Artist writing:

-

Unpacking (after) a coyote walk. Walking Lab residency, 2017. Link.

-

Connective filaments, coyote walks on the map. Living Maps Review No. 2, 2017.

Link / Download PDF -

Tracking the call of the wild from the heart of Manhattan. NYNJ Trailwalker Summer 2012. Download PDF

Speaking:

-

Artists and the Post Industrial Urban Wilderness, Union Docs, 2017. Link

-

Chance Ecologies Symposium, Queens Museum, 2016. Link

-

Re-inscribing the City: Unitary Urbanism Today, Anarchist Book Fair, 2011. Link

Referenced:

-

Urban Coyotes Spur Walks on the wild side. CUNY NYCity News Service. Audio piece by Samia Bouzid

-

“‘Uurga shig’ – What is it like to be a lasso?” Hermione Spriggs, Journal of Material Culture, 2016. Link

-

Out Walking the Dog blog, Melissa Cooper 2011-12. Link

-

City Reliquary event write up in Matt Levy’s Action Direction blog, 2009. Link

Amanda Heng, Every Step Counts (2019)

- Amanda Heng “Every Step Counts” (2019)

- Amanda Heng “Every Step Counts” (2019)

- Amanda Heng “Every Step Counts” (2019); Passers-by looking at the video of Amanda Heng’s work projected onto the walls in the Esplanade tunnel.

Multi-disciplinary project: workshop, text work in public space, archival footage, video projection and live performance

Dimensions variable

Collection of the Artist

Singapore Biennale 2019 commission

“Contemporary artist, curator and lecturer Amanda Heng (b.1951, Singapore) is known for making art that explores real-world issues through everyday activities – whether it’s walking, peeling beansprouts, or having coffee. Her recent work for the Singapore Biennale, titled Every Step Counts, draws upon the act of walking and takes an introspective look at the ageing body and how it is impacted by the rapidly evolving social and cultural environments.

Every Step Counts is a project spanning May 2019 to March 2020. The work comprises a two-day walking workshop, a text work, archival footage, a video projection and a series of live performances. The larger-than-life text work is featured on SAM’s hoarding along Bras Basah Road, while the video projection is exhibited at the Esplanade tunnel, joining the line-up of outdoor artworks displayed during the Singapore Biennale 2019.

WALKING IS A CENTRAL FEATURE IN MANY OF AMANDA HENG’S WORKS

Influenced by the Taoist principle of “working with rather than against nature”, Amanda sees walking as a form of meditation, a ritual from which to draw inner strength.

“It has to do with my intention of examining the body, which is an important element in live performances. The body is actually a live organic element that grows and gets old. This aged body – how should I look for the continuity of practising, of using it?”

KEEPING THINGS SIMPLE YET MEDITATIVE

Doing away with all bells and whistles, Amanda chose to present her work as a single line of text standing as a backdrop against a busy street; blue to represent the sky – a constant to anyone, anywhere; white to uplift; and bold italics to represent spirited movements. She hopes its simplicity will stop people in their tracks to savour the words amidst the hustle and bustle of life.

THE AUDIENCE COMES FIRST

Every component of Every Step Counts engages people in different ways. The workshop, for instance, involved nine participants spending two days charting their own routes of walking, who later had their walks filmed and are now being projected onto the walls of the Esplanade tunnel. It is hoped that when passers-by walk alongside these participants, albeit in a different space and time, they will become more attuned to their surroundings and their own pace.” [credit]

“Every Step Counts is exhibited at Singapore Art Museum on the hoarding, as well as Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay. This work also comprises a series of performances.

Amanda Heng invites participation and intimate conversations in her performative works. Often, she harnesses everyday situations to explore issues like the complexities of labour or the politics of gender. For her project in this Biennale, Heng revisits her ‘Let’s Walk’ series, first performed in 1999. Drawing upon the act of walking, the artist moves forward, looks back, turns inward and ventures outward with others. In this piece, she returns to the seminal scene of the walk and facilitates a workshop with people who chart their own routes of walking, and with whom she walks. In so doing, she generates reflections and perspectives, as well as comes to terms with the limits and stamina of the aging body.” [credit]

Lisa Myers, and from then on we lived on blueberries for about a week (2013)

Lisa Myers, ‘and from then on we lived on blueberries for about a week’, made for MAP Spring 2013, 6’44” (animation with assistance from animator Rafaela Kino). This work pays homage to an on-foot journey her grandfather undertook to flee Shingwauk Residential School in Ontario. Myers herself once did an 11-day walk tracing the route of her grandfather’s journey.

“When he was a boy, artist Lisa Myers’s Anishinaabe grandfather walked some 250 kilometres along Northern Ontario railroad tracks for one reason: to escape Shingwauk Residential School in Sault Ste. Marie.

Myers recorded her grandfather’s account of this journey during a conversation with him in the 1990s—and she listened it to it many times before she made the decision, in 2009, to walk the route he’d described alongside her cousin Shelley Essaunce and her nephew Gabriel.

Myers and the Essaunces took 11 days to walk the 250-kilometre journey.

“After this walk,” Myers writes in a 2016 Walter Phillips Gallery exhibition essay titled “Rails and Ties,” “I began thinking about how to locate myself within my grandfather’s story, and about how I wanted to convey its different iterations. One thing that struck me was that he survived by eating blueberries growing along the tracks. He said, ‘and from then on we lived on blueberries for about a week.’”

The latter quotation from her grandfather became the title for a video installation by Myers—one related to trauma, food, walking and survival—that was on view at Artcite in Windsor this spring as part of the exhibition “Walks of Survivance.”

“Instead of always repeating his story, [walking] was a way of finding myself in that story,” Myers told curator Maya Wilson-Sanchez a few years ago. And by walking, Myers also told Wilson-Sanchez, she was “able to bring the places in the story to life.”

“When I recall walking across the railway bridge over the Mississauga River north of Lake Huron,” Myers writes in “Rails and Ties,” “I think about my fear of the elevation, and how gusts of wind unsteadied my steps. Finding my footing meant looking down and seeing the river rushing 50 feet below the railway ties of that century-old steel bridge. The Mississagi River flows into Lake Huron, the railway crosses the river, and from my grandfather’s account of his journey this was the first place (after leaving school) where he heard his language and saw Anishinaabe people cooking and sharing food down by the river. They welcomed him, and fed him.”

During her walk in her grandfather’s footsteps, Myers also heard stories of other youth who had escaped the way he had. Ultimately, her works on this theme—which include both abstract and map-like prints made with blueberry pigments, as well as documentation of wooden spoons stained with blueberries she has shared with others, also speak to a complex intertwining of group and individual journeys, of landscapes that are real and imagined.

- Lisa Myers, “Blueprint Garden River bridge” (2015)

- Lisa Myers, “Tracking My Blueprints blueberry, rolling pin wood block print variable” (2012)

- Lisa Myers, still image from then on we lived on blueberries for about a week, 2015.

“The spoons represent sharing, sustenance and the gathering of people,” Myers writes. “When I line these spoons up side by side, the reddish-blue marks continue from one utensil to the next, recalling an imaginary topography or horizon line created by the trace of berry consumption.”

In this sense, walking and artmaking become different ways of tracing and “straining” an experience.

“Straining to survive, or even to be accepted, means the less digestible parts of stories need to be retained, traced, remembered and told,” Myers writes.

Of course, Myers is not alone in thinking about walking as a mode of Indigenous resistance and survival.

“There’s the water walk that is happening, and which is not directly art-related,” Myers said in a phone interview. “But I think Indigenous artists are wanting to also acknowledge that these forms of activism are happening. There was walking from a community in Nunavut, [Idle No More] walking to Ottawa to make a point.”

“Walking to safety is a really important narrative in talking about survival, and surpassing survival to freedom,” says “Walks of Survivance” curator Srimoyee Mitra.” [credit]

Lisa Myers, ‘Blueberry Spoons’, 2010, video, 7’37”

Eric Andersen, The MassDress (1985)

- Eric Andersen, “The MassDress” (1985)

- Eric Andersen, “The MassDress” (1985)

- Eric Andersen, “The MassDress” (1985)

- Eric Andersen, “The MassDress” (1985)

- Eric Andersen, “The MassDress” (1985)

- Eric Andersen, “The MassDress” (1985)

- Eric Andersen, “The MassDress” (1985)

[credit]

“Costume by Eric Andersen

Performed by The Group Berzerk

During the art fair Art in 1980 in New York, Gallery Interart from Washington arranged a sensational Fluxus Buffet from October 10 through 18, 1980. The following artists participated: Eric Andersen, George Brecht, Joe Jones, La Monte Young, Yasunao Tone, Nam June Paik, Takako Saito, Mieko Shiomi, Daniel Spoerri, Emmett Williams, AY-O, Geoff Hendricks, Dick Higgins, Alison Knowles, Yoshimasa Wada and Bob Watts. For the occasion Eric Andersen produced a Dinner Dress for 30 people. The costume is part of a series of possible shared costumes for which function overrules convention. Among these costumes are a TV Costume for 1 to 10 people, a Soccer Costume for 11 people, an Industry Costume for 5 to 10,000 people, a Big City Costume for 5 to 10 million people, an Erotic Costume for 3 to 99 people, a Witness/Victim Costume for more than 2 people and a Debate Costume for fewer than 179 people.

In 1984 in Copenhagen, the group Berzerk performed The Idle Walk of the Year for Eric Andersen – a procession stretching from The Ethnographic Collection at The National Museum through The National Bank to the courtyard of Amalienborg Castle. During the Festival of Fantastics, Berzerk performed with the 30 people costume carrying out an extensive choreography. Initially, the performers put on every second part of the costume, conducting a procession across Stændertorvet. Then audience members were invited to enter the remaining fifteen costume parts. The ensuing procession climbed ladders on fire department vehicles and stretched through city streets, alleys, busses and shops. The whole performance lasted more than two hours.

Eric Andersen’s description of The MassDress“

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, Violin Phase from Fase: Four movements to the Music of Steve Reich (1982)

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker

“MoMA’s Performance Exhibition Series presents a program of live performance and dance in conjunction with the group exhibition On Line: Drawing Through the Twentieth Century. The dancing body has long been a subject matter for drawing, as seen in a variety of works included in this exhibition. These documentations show dance in two dimensions, allowing it to be seen in a gallery setting. But if one considers line as the trace of a point in motion—an idea at the core of this project—the very act of dance becomes a drawing, an insertion of line into time and the three-dimensional space of our lived world.

Choreography and dance: Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker

Music: Steve Reich, “Violin Phase” (1967)

Violin: Shem Guibbory

Duration: 16 minutes

Created at the Dance Department of New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, first performed in April 1981 at the Festival of Early Modern Dance, Purchase, New York.

Rosas is the dance ensemble and production structure built around the choreographer and dancer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker. Find out more at www.rosas.be.” [credit]

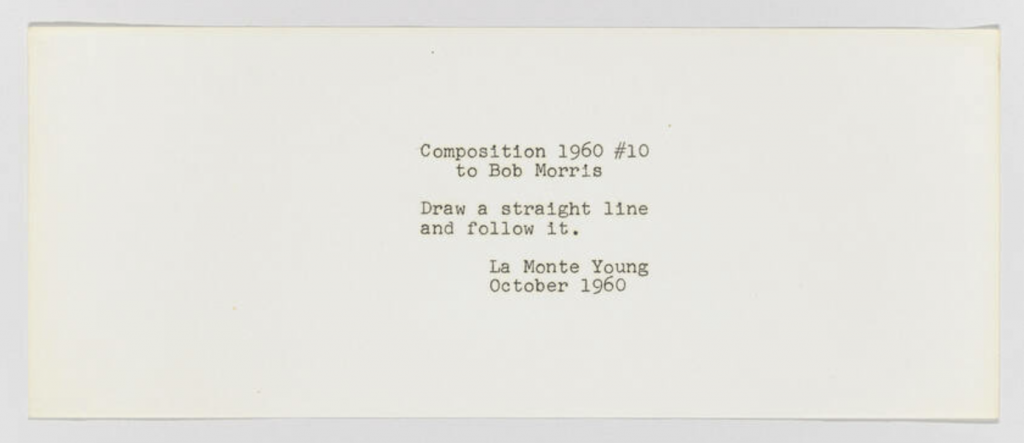

La Monte Young, Composition 1960 #10

La Monte Young “Composition 1960 #10” (1960) typewriter ink on paper, 3 3/8 × 8 9/16in.

La Monte Young‘s Composition 1960 #10, simply states, “Draw a straight line and follow it.” Young (1935-) was a well-known member of Fluxus.

Credit: Waxman, Lori. Keep Walking Intently: The Ambulatory Art of the Surrealists, the Situationist International, and Fluxus. Sternberg Press, 2017. Page 206.

—

Nam June Paik “Zen for Head” (1962) [credit]

—