[credit]

I am the Locus (#2)

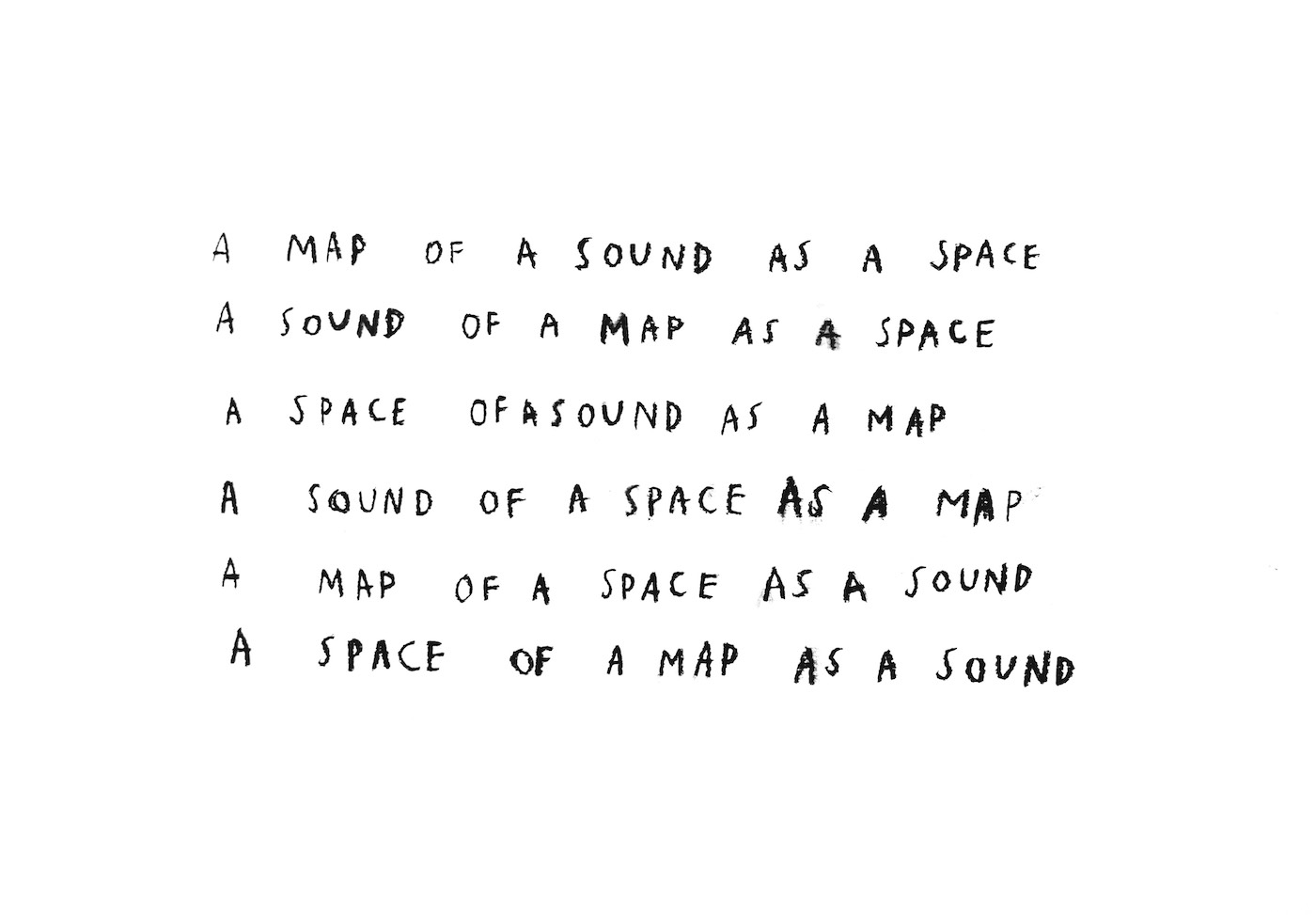

DimensionsSheet: 8 x 10 in. (20.3 x 25.4 cm)

“The series of five hand-worked photographs that comprise The Mythic Being: I am the Locus conveys Piper performing a consciousness of otherness on a walk through Harvard Square in Cambridge, Massachusetts. An American-born artist of mixed racial background, Piper has articulated questions about the politics of racial identity in many ways throughout her work as an artist and philosopher. In 1973, Piper created an alter ego, the Mythic Being, who became the basis of a pioneering series of performances and photo-based works. For this 1975 Mythic Being performance, she sported large sunglasses, an Afro wig and mustache—chosen to blend in with the mid-seventies urban environment, and dressed in men’s clothing. This simple costume enabled her to appear inconspicuously as a black man to an unknowing public. In these photographs we can perceive the indifference of the crowd in Harvard Square to Piper’s performance: people brush shoulders with her, or look in the opposite direction.

Her subsequent intervention into the photographs with oil crayon and text helps to dramatize the scenes, and to express the tension between the artist’s inner experience and the invisibility of her Mythic Being performance to its live audience. Drawing directly on the photographic prints prevents the images from being seen as straightforward documentation of a performative event. Instead, by the final sequential image, most of the other people and surroundings have been obliterated by drawing, which parallels the text’s shift from philosophical meditation (“I am the locus…”) to existential shove (“Get out of my way…”). Piper intended for these photographs to be made into posters; she did not initially intend for these preparatory images to be treated as works of art unto themselves.” [credit]

—

“In 1973 Adrian Piper pasted a mustache on her face, put on an Afro wig, and donned round, wire-rimmed shades.

Dressed and acting like a man, she went out into the streets.

Muttering passages she had memorized from her journal, the artist was startling and weird, challenging passersby to classify her through the lens of their own preconceptions about race, gender, and class.

Who was this light-skinned black man, going on and on about how his mother bought too many cookies. Was he crazy? Was he dangerous? Why was he being followed by a film crew?

These street actions formed the basis of The Mythic Being, an influential work of performance art that helped establish Piper’s reputation as provocateur and philosopher.

At a time when Conceptual and Minimal art were mostly male domains that pushed to reduce art to idea and essence, Piper pushed back with confrontational work that brought social and political issues to center stage. And at a time when most performances were barely documented, Piper announced her project in ads in the Village Voice, arranged for it to be filmed by Australian artist Peter Kennedy, and created works on paper dominated by her aggressive alter-ego.

In the catalogue for “Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art,” currently at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery, curator Naomi Beckwith describes Mythic Being as “a seminal work of self-fashioning that both posited and critiqued models of gender and racial subjectivity.”

Footage from Mythic Being, borrowed from Kennedy, had been playing on a monitor in the Grey’s galleries until this week—when Piper requested the work be removed. The monitor was turned off and the gallery posted a note to viewers on top.

It explained that the artist had articulated her reasons in correspondence with Valerie Cassel Oliver, the show’s curator, which reads in part:

“I appreciate your intentions. Perhaps a more effective way to ‘celebrate [me], [my] work and [my] contributions to not only the art world at large, but also a generation of black artists working in performance,’ might be to curate multi-ethnic exhibitions that give American audiences the rare opportunity to measure directly the groundbreaking achievements of African American artists against those of their peers in ‘the art world at large.’”

The note responds with a statement of Cassel Oliver’s from the catalogue, arguing that the show’s mission is to resist “reductive conclusions about blackness: what it is or what it ain’t. What is clear is that it exists and has shaped and been shaped by experiences. The artists in this exhibition have defied the ‘shadow’ of marginalization and have challenged both the establishment and at times their own communities.”

In response to Piper’s request, Cassel Oliver added: “It is clear however, that some experiences are hard to transcend and that stigmas about blackness remain not only in the public’s consciousness, but also in the consciousness of artists themselves. It is my sincere hope that exhibitions such as Radical Presence can one day prove a conceptual game-changer.”

In depriving students and the larger public from seeing her work at the Grey, the artist, who currently lives in Berlin and runs a foundation dedicated to art, philosophy, and yoga, has chosen to make a larger point about marginalization and otherness, themes that have dominated her work throughout her career.

The question is whether separate exhibitions are still needed to tell the stories that were left out and continue to be absent from conventional tellings of art history, or whether creating these separate spaces amounts to a kind of ghettoization that prevents the artwork from being considered on the larger stage.

These issues are hardly confined to race, of course—curators of exhibitions on gender, nationality, and other aspects of identity routinely encounter artists who decline to participate because they don’t want to be considered in the context of “women artists,” “Jewish artists,” and so on. So, sometimes, do our contributors and photo editor when we run stories on these issues.

The organizers of “Jew York,” a show at Zach Feuer and Untitled galleries in New York last summer, were turned down by several artists who didn’t want to appear under such a rubric. Luis Camnitzer, a German-born Uruguayan artist, was so conflicted that he couldn’t decide whether to recuse himself or contribute a piece. So he sent a letter describing his conundrum, which became part of the show. It read in part: “Do I refuse the invitation on the grounds of feeling that it is an artificial and anecdotal grouping irrelevant to the work of most artists invited and therefore tinged by an aroma of weird fundamentalism? Or do I have to accept on the grounds of my need not to deny my Jewish connections bound by my ethical debt and beliefs? Maybe not totally pleasing to everybody, this letter tries to be my compromise.”

When “Radical Presence” opened at the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, last year, it also included five works from Piper’s 1975 series I am the Locus, collaged and painted Polaroids on which images of Piper as the Mythic Being are inserted into scenes of a crowded street. The text gets bigger as the figure approaches the viewer, culminating in the warning “Get Out of My Way, Asshole.” The works, owned by the Smart Museum at the University of Chicago, were deemed too fragile to travel to New York.

Part II of the New York version of “Radical Presence” opens at the Studio Museum in Harlem on November 14. It doesn’t include any works by Piper. The show is scheduled to travel to the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis next year.” [credit]