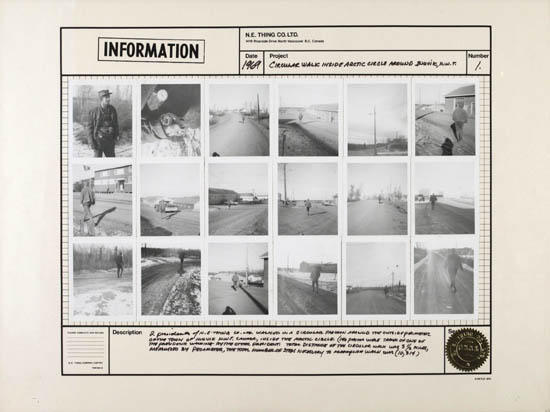

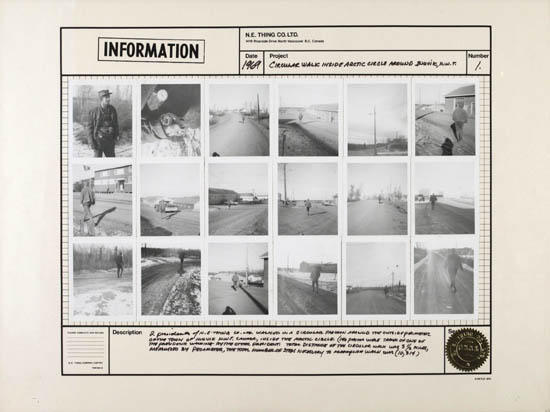

Circular Walk inside Arctic Circle, Around Inuvik, N.W.T., 1969 silver prints, ink, paper, foil seal, offset lithograph on paper; 44 x 44 cm Collection of the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, University of British Columbia. Gift of Iain Baxter & and Ingrid Baxter, 1995 [credit]

“The concept of everydayness does not therefore designate a system, but rather a denominator common to existing systems including judicial, contractual, pedagogical, fiscal, and police systems. Banality? Why should the study of the banal itself be banal? Are not the surreal, the extraordinary, the surprising, even the magical, also part of the real? Why wouldn’t the concept of everydayness reveal the extraordinary in the ordinary?

—Henri Lefebvre

By making life more interesting for others, we may indirectly help to alleviate the human condition. We up your aesthetic quality of life, we up your creativity. We celebrate the ordinary.

—N.E. Thing Company

“To change life-style,” “to change society,” these phrases mean nothing if there is no production of an appropriated space.

—Henri Lefebvre

Throughout their collaboration (1966–1978), Iain and Ingrid Baxter utilized the N.E. Thing Company—their incorporated business and artistic moniker—as a vehicle through which to investigate artistic, domestic and corporate systems in relation to their everyday life. Like typical West Coast and Canadian artists, the Baxters made landscapes, though theirs were expanded to include the sites of work and leisure, and urban and suburban spaces. They were uninterested in painting pictures of Canadian wilderness as a hostile, unexplored territory full of myth, mystery or awe-striking grandeur—all that is other to the obvious and banal spaces of the everyday. Instead the Company’s landscapes investigated how information technologies, corporate relations and institutions such as the art world and the nuclear family interact to redefine “landscape” as a product of human interest, an element of subjectivity and charted its relationship to forms of identity and national positioning. NETCO’s reversals, reflections, inflatables, mappings, punnings, and measurements, disrupted unidimensional, unidirectional hegemonic annexations of space. The Company actively appropriated and transformed these spaces to allow for creative possibilities and critical potential. At the same time as the Baxters’ landscapes attempt to map out a coherent picture of fragmented realms, in a move that is characteristic of the contradictions explored in their work, these landscapes stake out a social topography in the emerging, geo-politically peripheral city of Vancouver in the late sixties.

Although the Baxters were contemporaries of the Situationists (who were among the first to incorporate Henri Lefebvre’s analysis of everyday life into their practice), it is necessary to distinguish NETCO from its French counterparts. Lefebvre and the Situationists saw everyday life as a site of revolutionary potential to be liberated through aggressive reversals and combative tactics of negation—a space from which to undermine the corporate state through dialectical analysis of and critical intervention in consumer society that revealed the stakes capital has in maintaining a separation between the realms of work and leisure, the political and the everyday.[1] Although the Baxters attempted to integrate the spheres of work and leisure, they aimed to open potential spaces of creativity within existing economic and political constraints by breaking down habitually assumed modes of perception in order to up the quality of life—a life that took account of family, business, and art activities. The Baxters proposed an agency that was expansive, inclusive and celebratory in place of the Situationist’s disruptive and radically motivated interventions. They playfully questioned their roles as entrepreneurs, artists, educators, parents and spouses, collapsing and infecting systemic boundaries in order to reinvestigate the elusive and taken-for-granted. …

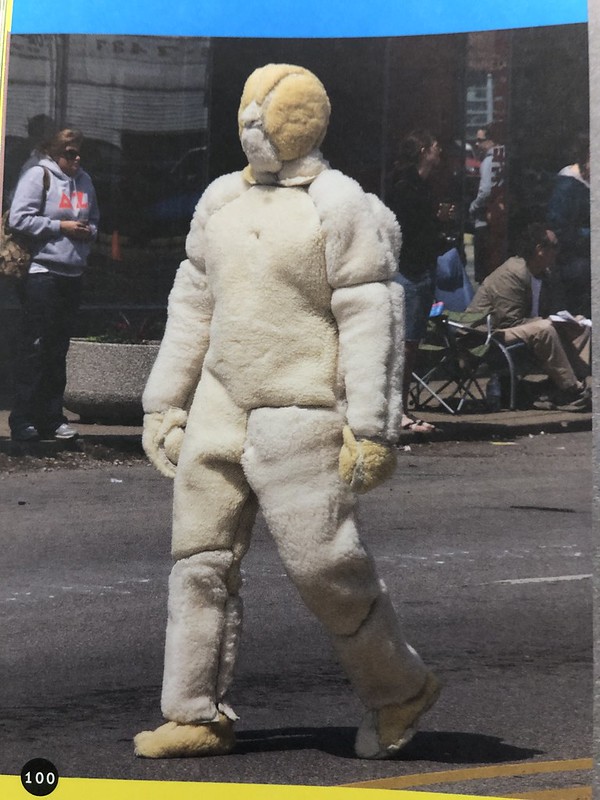

As urban and corporate explorers, the Baxters set out on many sightseeing expeditions. In Circular Walk Inside the Arctic Circle Around Inuvik, NWT (1969) the Company presidents wore pedometers to scientifically mark the seven km or 10,314 steps travelled around the circumference of Inuvik. … The Arctic work, as well as other landscape pieces, were accompanied by standard road and geographical maps that the Baxters marked with instructions and drawings. In doing so they transformed official maps from representations of regulated and unidimensional space into dynamic and contingent space. By inflecting mapmaking practice with their actual experience of and activities in Inuvik, the Baxters transformed abstract and instrumentalizing concepts into the realm of the everyday, disrupting the objectivity of the rationalized grid that presupposes a homogeneous subject, and a static space that ignores time and history.” [credit]

“Influenced by business studies and the theories of Marshall McLuhan, N.E. Thing Co. Ltd., and its treatment of art as “Sensitivity Information, ” has left a lasting impression on Conceptualism in Canada and abroad. Founded by Iain and Ingrid Baxter in 1966 and dissolved in 1978, N.E. Thing Co. began in a blur of short-lived corporate monikers. …

… the Baxters first used the alias N.E. Thing Co. in 1967. Following the company’s formal incorporation in 1969, they named themselves co-presidents in 1970. In this way, it was equally through the form of their practice—as co-presidents of a corporate structure—that made NETCO an instructive example in collaborative artmaking. However, as Marie Fleming suggested in her survey of the Baxters’ early work in 1982, it is difficult “to assess clearly the nature and development of the collaboration and to distinguish the individual contributions of Iain and Ingrid Baxter to work produced under the various rubrics. The issue has become sensitive since their separation in 1978.”2

By making use of technologies previously reserved for businesses – such as the telex and telecopier—the Baxters capitalized on their relatively peripheral situation.”

2N.E. Thing Co. (Vancouver: self-published, 1978), not paged.

[credit]