[credit]

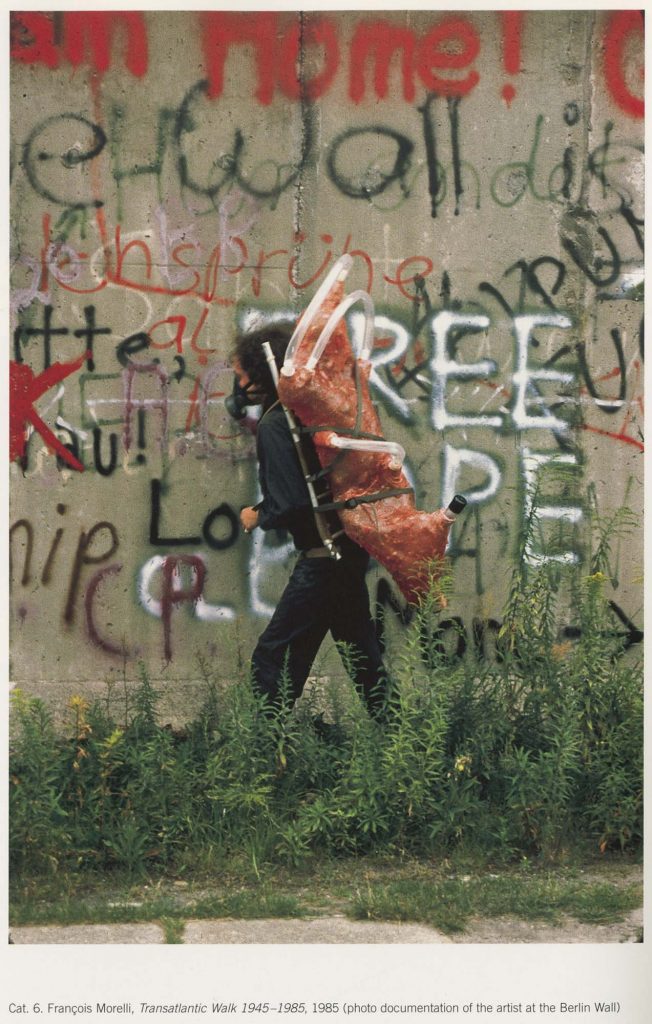

In the Alien Staff project, alien means a state of being and ‘becoming’ both political and metaphysical, nomadic and migrant – a sort of psychological encampment in the space and time of today’s displaced and estranged world.

No aliens, residents, non-residents, legal and illegal immigrants have voting rights, nor any sufficient voice nor image of their own in official “public space”. When given a chance by the media (mainstream or ethnic) to communicate their experience or to state their opinions, demands and needs, immigrants find themselves framed and silenced.

The Alien Staff is a form of portable public address equipment and cultural network for individuals and groups of immigrants. It is an instrument that gives the individual immigrant a chance to “address” directly anyone in the city who may be attracted by the symbolic form of the equipment and the character of the “broadcasted” program.

The Alien Staff resembles the biblical shepherd’s rod. It is equipped with a high-tech mini-monitor and a small loud-speaker. The central part of the rod, the ‘Xenolog section’ is made up of interchangeable cylindrical containers for the preservation and display of precious relics related to the various phases of the owners history. A small image on the screen may attract attention and provoke observers to come very close to the monitor and therefore to the operator’s face, the usual distance from the immigrant, the stranger, decreases.

Upon closer examination, it will become clear that the image on the screen and the actual face of the person are of the same immigrant. The double presence in ‘media’ and in ‘life’ invites a new perception of the stranger as ‘imagined’ (a character on the screen) or as ‘experienced’ (an actor off-stage – a real life person). Since both the imagination and the experience of the viewer are increasing with the decreasing distance, while the program itself reveals unexpected aspects of the actor’s experience, the presence of the immigrant becomes both legitimate and real. This change in distance and perception might provide the ground for greater respect and self-respect, and become an inspiration for crossing the boundary between a stranger and a non-stranger.

As the identities of these persons are not only unstable but also often in antagonistic relation to each other, the only common ground they share is their resistance against any imposed (even self-imposed) uniform or generalised notion of a so-called immigrant identity.

The first model of the Alien Staff was built and tested in Barcelona in June 1993, following the first comprehensive exhibition of Wodiczko’s work in Europe in 1992, entitled Instruments, Projections, Vehicles, at the Fondació Antoni Tapies, Barcelona. A second model was built and its design further transformed in Brooklyn during the summer, fall and the winter 1992-93. The Alien Staff was used by many immigrants in New York, Paris, Houston, Marseille, Stockholm, Helsinki, Warsaw.

In Rotterdam, before and during Next 5 Minutes (1996), local operators walked through the city with Krzysztof Wodiczko projects Alien Staff and Mouth Piece. Aided by electronic walking sticks and mouth-size monitors they demonstrated how to communicate in an unfamiliar cultural environment and language.