“I have always loved walking by the sea and was increasingly disturbed by the amount of plastic I was finding washed up on the beach. But in 2006, the United Nations Environment Programme reported that humankind’s exploitation of the oceans was ‘rapidly passing the point of no return’ and I was really shocked to discover that they estimated that on average there were around 46,000 pieces of plastic litter floating on every square mile of ocean, leading to the death of over one million seabirds and over 100,000 marine mammals every year due to entanglement with or swallowing of litter.

We now know that over 12 million tonnes of plastic end up in our oceans every year, travelling on ocean currents to every part of the globe. These plastics endure in the marine environment indefinitely: items from the birth of plastics are washing up on our shores, virtually unscathed. Scientists estimate that plastic can take 1000 years or more to degrade in seawater and even then will continue to pollute our environment with thousands of microscopic fibres: samples taken from a Northumbrian beach were found to have over 10,000 fibres in just one litre of sand… But disposal of plastics in our oceans isn’t just harming wildlife now. We are also providing a toxic legacy that may last an eternity. Moreover, plastics can be found throughout the food chain, even ending up in the food on our plates.

|

plastics, like diamonds, are forever…

|

The Challenge

I was so shocked by what I had learned, I felt I had to do something and resolved to ‘save’ one square mile of ocean by collecting 46000 pieces of litter whilst walking on the beaches near my home. Every time I visited the beach I picked up all the litter I could carry. My challenge took exactly a year to achieve (September 2006 – September 2007) and in total I walked over 200kms and carried away nearly a third of a tonne of rubbish.

But sadly my challenge will never really be complete. Scientists estimate that the amount of plastic in the sea is increasing at a rapid rate, doubling every 2 or 3 years. I’m still collecting (I can’t stop!). But this could be a lifetime’s work and I still might not save a single square mile of sea…

My efforts may only be a literal splash in the ocean compared to the immensity of the problems are seas are facing. But what if everyone tried to do something about it? Luckily there is a lot more we can do – have a look here at the things we can all do…

Whilst walking, I took photographs and created a book of what I saw, contrasting the seemingly unspoilt beauty of the landscape with the man-made debris which inhabits it.

See my photographs in sequence from the beginning of my challenge.

To see specific locations, click the following links:

Aldeburgh – Bawdsey – Covehythe – Dunwich – Felixstowe – Orford Ness – Shingle Street – Sizewell – Southwold – Thorpeness – Walberswick

Collecting

I have saved and photographed nearly everything from my walks.

See some of my collections.

Exhibitions

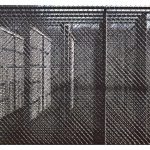

The plastics I have collected have become my materials: I create huge installations with what I have found, ‘recycling’ it as art with potent message, playful but deadly serious.

See photographs from some of my exhibitions.“

[credit]