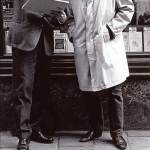

Jeremy Wood

Jeremy Wood

[credit]

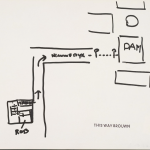

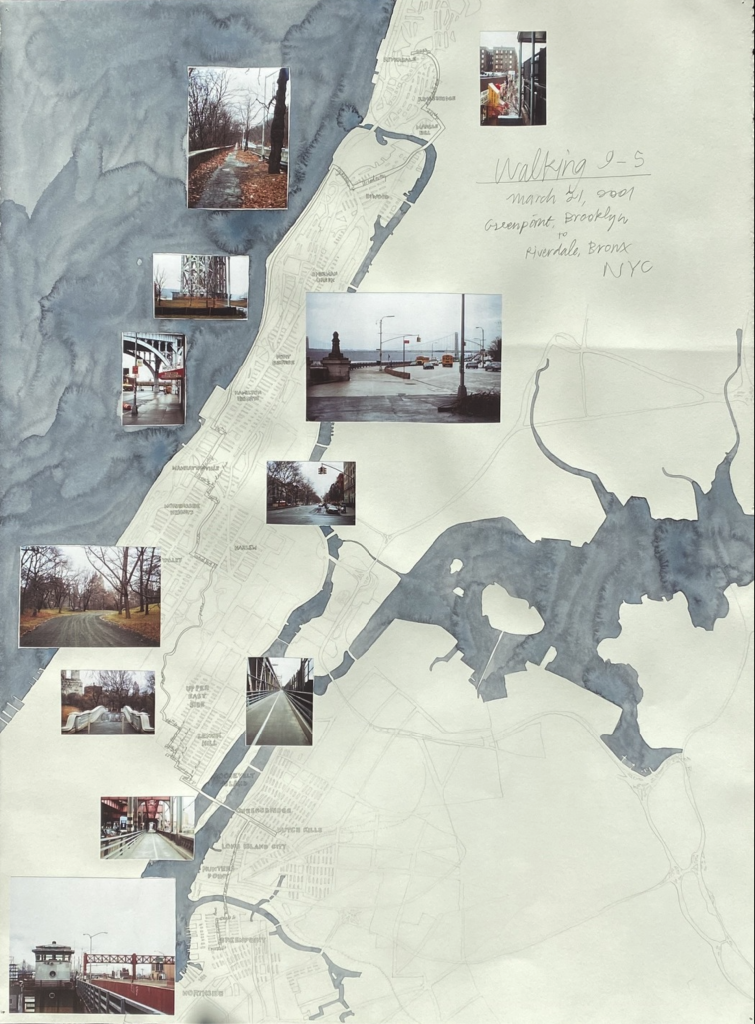

“Jeremy Wood describes himself as “an artist and mapmaker”, and was one of the first artists to make use of GPS technologies creatively. These technologies have allowed him to trace his daily movements and to present a personal cartography. “Most GPS receivers record your whereabouts as a track, like a dot-to-dot or a digital breadcrumb trail. When the line is viewed on its own, you have a GPS drawing”, the artist says.

‘White Horse Hill’ is a scaled cardboard representation of forty-three kilometers of GPS tracks of methodical walks over the area round White Horse Hill in Uffington, Oxfordshire. The walking was informed by the making; a forty kilometre walk at 1:1 scale was translated into forty metres of card at 1:1000 scale. There were limitations; the walk had to achieve a certain density of tracks to capture the intricacy of the terrain, and no paths were to cross.

“We cannot know where we are on the ground without first looking up at the stars. The horse from the Bronze Age was made to be seen from the heavens and with Space Age navigation the heavens are used to see where we are. We don’t know why the figure of a horse was created, for a viewpoint unachievable then. And most of us don’t know how GPS works with orbiting satellites to tell us where we are now. The Uffington White Horse was chosen as a location for its wondrous communication between the ground and the sky; a relationship it has in common with the magical properties of satellite navigation technology.” (Jeremy Wood)”