“Heath Bunting emerged from the 1980s art scene committed to building open, democratic communications systems and social contexts. Throughout his career, he has explored multiple media including graffiti and performance art and has staged numerous interventionist projects, as well as being a pioneer in the field of Internet Art. Bunting began collaborating with artist Kyle Brandon in 2001.” [credit]

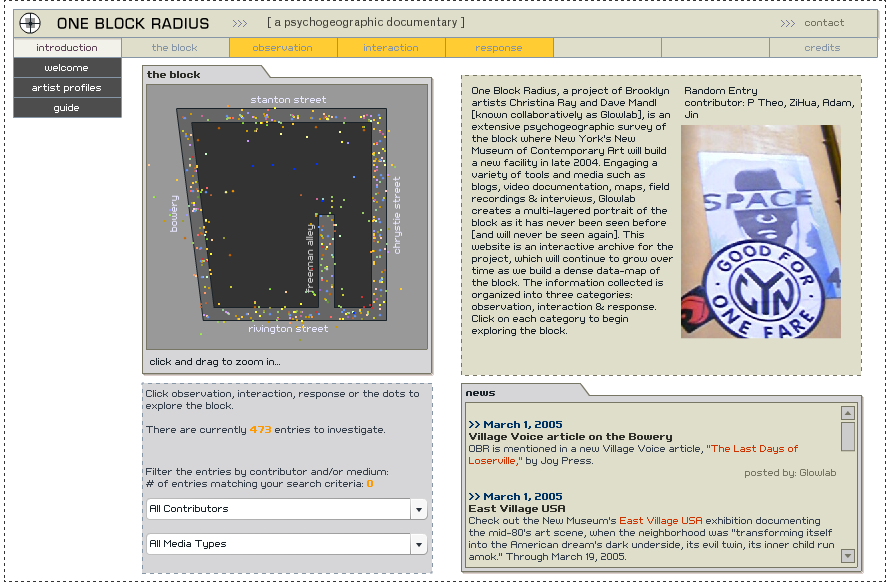

These artists devised a circular tour (see map), and by night stealthily cut some fences as part of their Borderxing project. BorderXing serves as a pratical guide to crossing major international borders, legally or illegally. It was a type of physical hacking of space, cutting anything that impeded their walk – D’Fence Cuts. Below is an excerpt from their tour de fence catalog:

“tour de fence is the answer to your real needs. while the internet promised to level out all barriers, tour de fence enables you to surmount the fences out there that people erect to obstruct your way every day. from wire netting to ru stic fence, from steel door to close security system, tour de fence offers you the necessary know-how for unhampered movement. tour de fence is the direct way.

learn offroad mobility within high security architecture. cross over stretches of land in the right direction. penetrate the underground area of your city. tour de fence puts an end to the relocation of your movements into virtual space. use the tour de fence! become a tour de fence amateur team. pass this handbook on to others. propagate tour de fence.

by doing so you will become part of the international tour de fence community. as a reader, a free-climber or by sending one of the 24 tour de fence postcard in this book.

participate now! tour de fence’s vision is to do what we want.

…

tour de fence acknowledges fence as metaphor for private property. fence as a supposedly temporary, often mobile barrier performing functions of inclusion and exclusion, entrapment and guided freedom, decoration, safety, user boun dary, protection from hazard, flow control, visual screening and user separation.

fence is a permeable filter system defining permitted use and users. light, wind, insects, water, plants and sound pass unhindered while high order life forms such as·humans, fish, cattle and cars are engaged:

development of fence.

up to now the vertical has generally been private while the horizontal public. increasingly, vertical fences are being rotated to the horizontal and enlarged over large areas of land, as all use and users are embraced in total control.

tour de fence recognises the transformation of framed freedom into restricted open-range roaming; the re-alignment of unknown possibilities into known re peatables. users are permitted to skate across flattened surface of fence, but not to pass through – the fence is everywhere.” (credit)