“At the end of January 1980, on the streets of Paris, I followed a man whom I lost sight of a few minutes later in the crowd. That very evening, quite by chance, he was introduced to me at an opening. During the course of our conversation, he told me he was planning an imminent trip to Venice. I decided to follow him.” – Sophie Calle

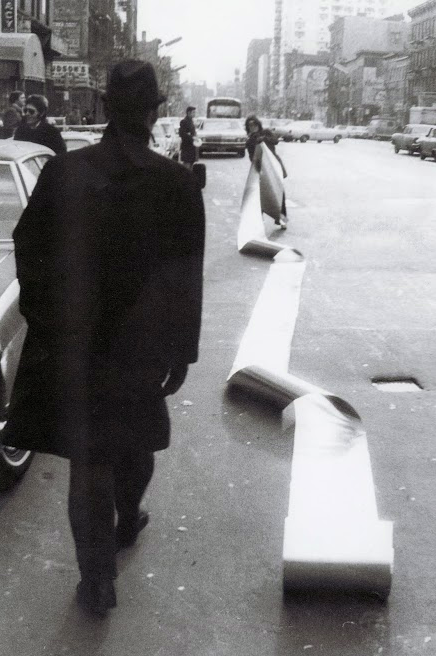

“Sophie Calle’s urban expeditions might be thought to recall Vito Acconci’s seminal performance work ‘Following’, made a decade earlier in which he tailed strangers chosen at random without their knowledge, up until they left public space for their homes or offices. In Calle’s work however, the relationship between the artist and their public is different. This is not merely because the expected gender roles, where men act as predators and women are vulnerable, are inverted. The artist’s motivations are unknowable, her ultimate goals opaque, and her behavior seemingly contradictory.

If we might imagine Acconci’s role implies that he is dangerous – is a stalker or assailant – Calle’s activities imply she is a kind of private detective or spy in pursuit of knowing more about a person than they do themselves. The presentation of her works as a kind of diary is intentionally alarming. We are meant to feel both a distance from her or repugnance at her behavior and, despite this, a simultaneous sympathy for or intimacy with her. Unlike a normal detective story, Calle’s work leaves us with both ‘who’ and ‘why’ left unresolved.” [credit]

“She met a man, Henri B., at a party. He said he was moving to Venice, so she moved to Venice and there, she began to follow him. Suite Vénitienne was the resulting book, first published in 1979 …Calle documents her attempts to follow her subject. She phoned hundreds of hotels, even visited the police station, to find out where he was staying, and persuaded a woman who lived opposite to let her photograph him from her window. Her photographs show the back of a raincoated man as he travels through the winding Venetian streets, a surreal and striking backdrop to her internalised mission. The very beauty of her surroundings has a filmic quality, intensifying the thriller-esque narrative of her project. Sometimes her means of following Henri B. are methodical – enlisting Venetian friends to make a phone call on her behalf – and sometimes arbitrary – following a delivery boy to see if he will lead her to him.” [credit]

Credit: //www.mersytzimopoulou.com/blog/2018/11/28/sophie-calle-suite-vnitienne-1979