Graphite on folded paper, 30.625 x 20.5 inches; CREDIT: //www.mutualart.com/Artwork/Walking-9-5–Graz/D328CC010A678FB5

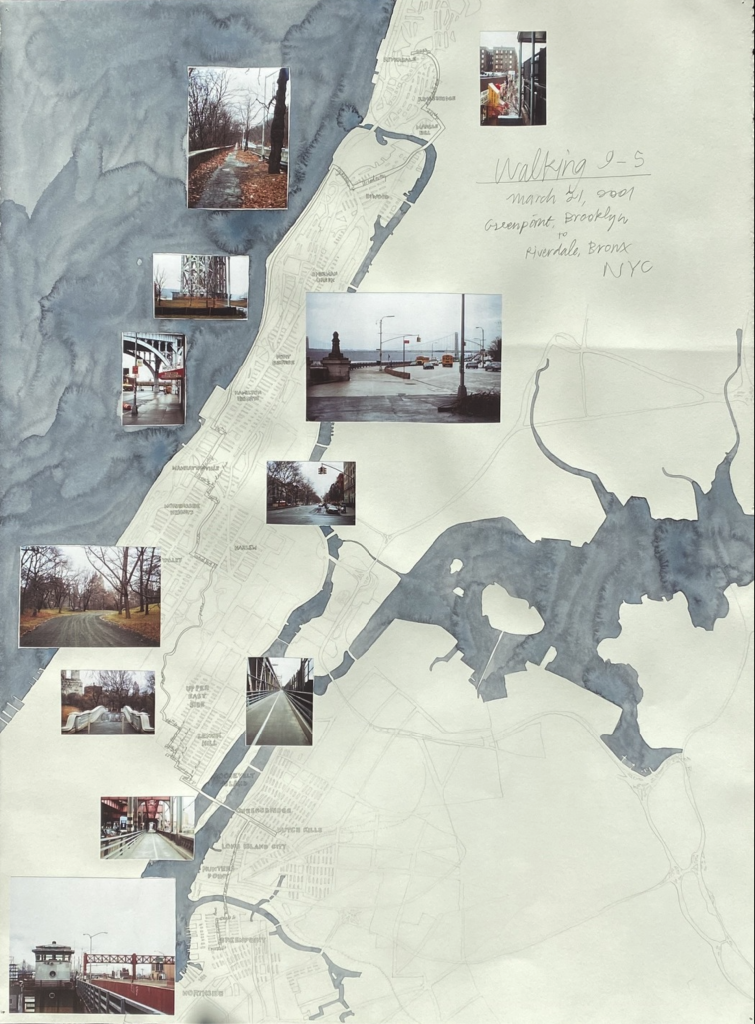

“Walking 9-5, March 21, 2001, Greenpoint, Brooklyn to Riverdale, Bronx, NYC” (2001), Pencil, watercolor and collage on paper, 30 × 22 1/4 in; CREDIT

- 116 small-sized drawings (2002)

- 116 small-sized drawings (2002)

The earliest work in the exhibition is Walking Amsterdam 9-5 , a sprawling installation of 116 small-sized drawings. Danica created this work in 2002 for the Amsterdam gallery Annet Gelink. She spent three weeks in the city, and 13 days walking through it, for exactly 8 hours every day. Point of departure for these excursions was always the central station, and every one of them proceeded in as straight a line as possible in all directions, 20° off the direction taken the previous day. At 5pm she would look for the nearest means of public transport in order to return to the city centre. One of her 8-hour hikes took her to a suburb of Utrecht, another all the way to Zanfort. The individual drawings on this wall are clustered by days. One lists all the day’s activities, the others represent situations and objects on which Phelps spent money. Every red stripe stands for a Dollar spent, and green stripe for a Dollar earned. The price of each drawing (from 30 to 800 Euros) depends on how much the artist likes the drawing. As she believes that the determination of the price is the final aesthetic decision, the price becomes part of the work itself – and is noted, in US$, on the drawing itself. If a certain drawing finds a buyer, Phelps creates a copy of it on tracing paper, which then replaces the sold drawing in the series. On this ‘second-generation’ drawing she paints a number of green stripes that corresponds to the price fetched by the original, the name of the collector, the gallery and the date of the sale. This in turn renders the copy unique again – and means that it is itself now up for sale. The presentation at Nolan Judin Berlin is the first chance since their exhibition in Amsterdam in 2002 to buy these drawings. [credit]