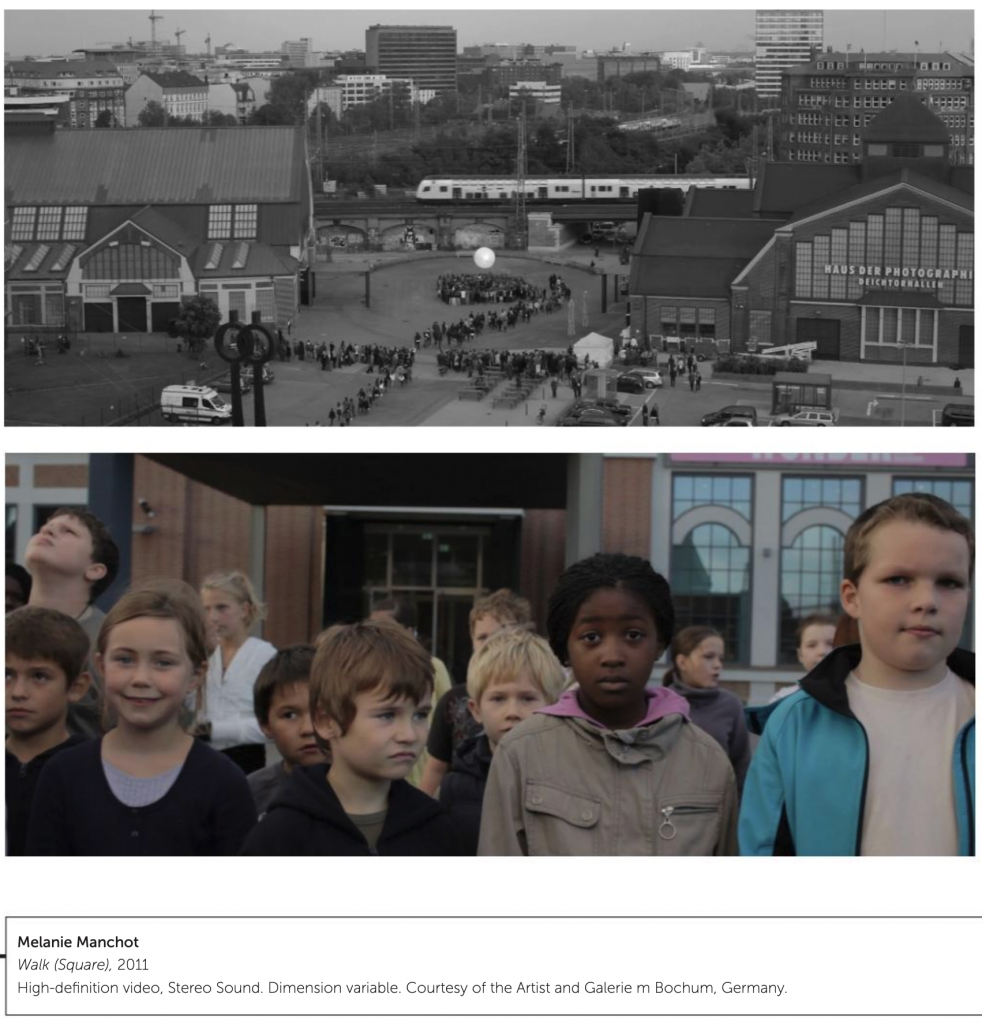

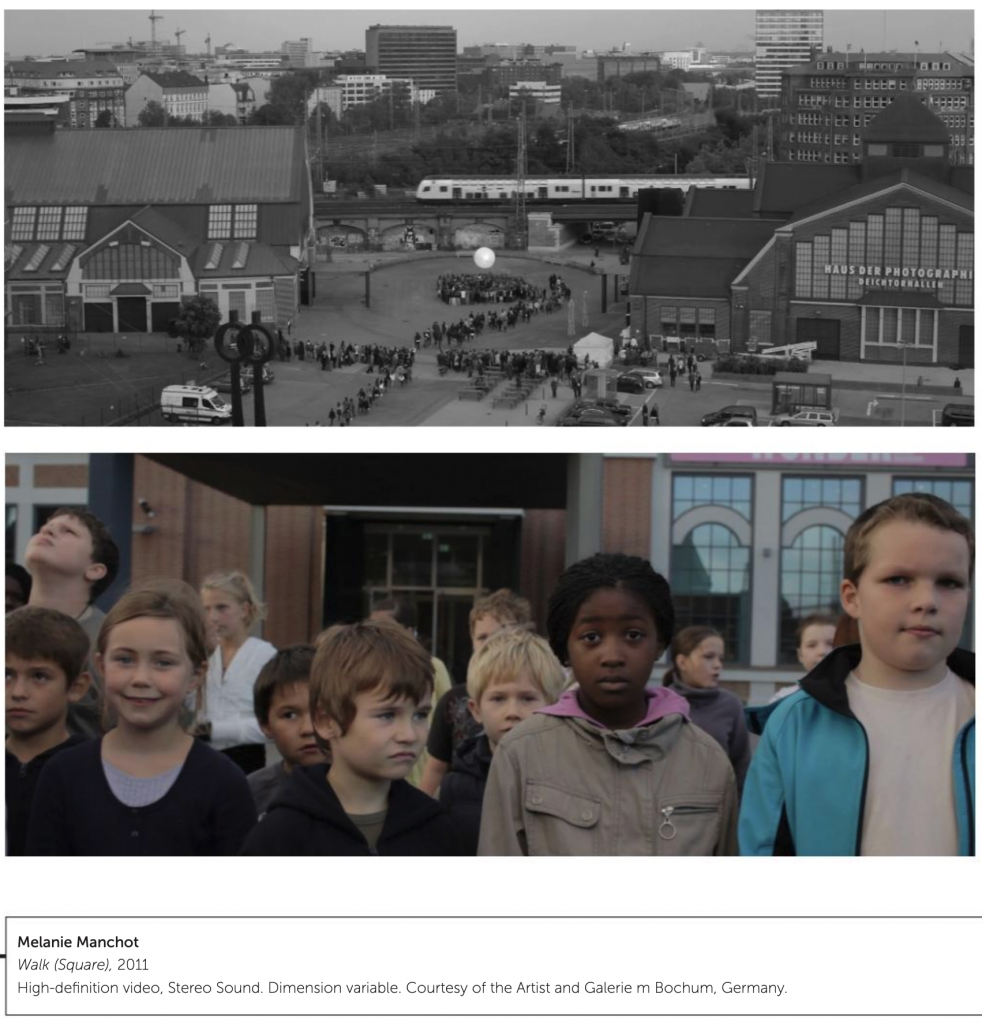

Walk (Square), 2011, Single Screen, HD, 20′40″

Walk (Square) forms part of an ongoing series of projects investigating collective gestures or situations enacted in public such as walking, dancing or celebrating. The work extends a practice based on an analysis of the construction of individual and collective identities and their performative representation through photography and moving image. Walking en masse—whether it be in processions, pilgrimages, in carnival or protest marches—forms the starting point for this video work made with 1000 Hamburg kids. Drawn into the centre of the city from all directions, with art as the ‘Pied Piper’, the work refers to current socio-political situations of protest as well as to recent research across different disciplines into the meanings of groups and crowds. The piece questions whether the act of walking may constitute a ‘form of speech’. On the square in front of Hamburg’s contemporary art museum a crowd of kids performs a simple walking choreography, based on Bruce Nauman’s video Walking in an Exaggerated Manner around the Perimeter of a Square, 1967– 1968, creating a shimmering form of movement that briefly produces a moment of collectivity and visual coherence before breaking apart.

[credit]

“At first glance, Melanie Manchot’s work shows us what might be a demonstration, a procession or a parade in the centre of Hamburg. The differences between the three, though seldom observed, are crucial. T h e historian David Cannadine has observed that when the French “put their social structures on public display they have parades (which are intrinsically egalitarian), whereas the British have processions (which are innately hierarchical)”. Demonstrations can be either hierarchical or not but, unlike the other two categories, are impossible to fully impose order on.

In ‘Walk (Square)’, a thousand children flock into Hamburg’s central square – with “art as the ‘pied piper”‘, as she puts it. Once inside the square, the children undertake what Manchot calls a “simple walking choreography” based on the Bruce Nauman work ‘Walking in an Exaggerated Manner Around the Perimeter of a Square’, seen elsewhere in this show. Manchot’s recreation of the earlier work in new form asks us to imagine how occupying public space has changed its meaning between ‘then’ and ‘now’. At the time of Nauman’s work, the purpose of protest was not in doubt, even if its efficacy was not universally accepted. Walking is, here, the means of occupying public space by traversing it. As Manchot puts it, “the act of walking constitutes a ‘form of speech'”. To walk – together – is in certain contexts a political act in the purest sense of the term. It is to ensure that one cannot be simply ‘walked over’ by those in positions of authority. To walk is to create “a moment of collectivity”, in the artist’s words.”