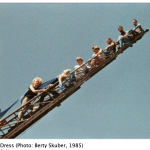

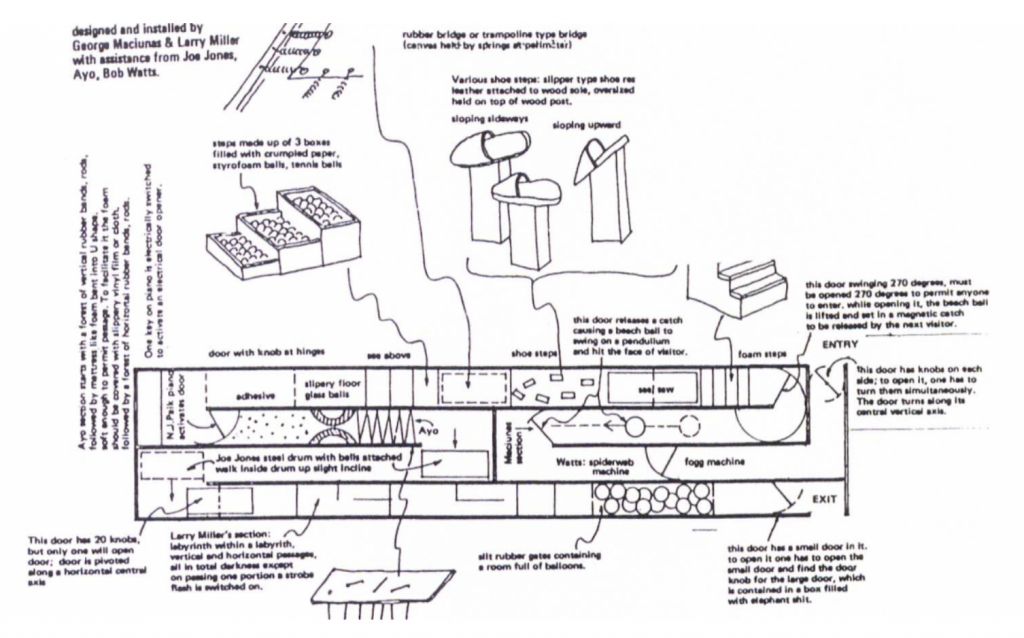

Read a full account of the Flux-Layrinth from initial plans in SoHo NYC, to the first execution in Berlin, and later a 2015 installation in NYC. [read more – includes images and plans]

“As Fluxus founder George Maciunas often referred to, Fluxus is gag-like, and Fluxus artists are jokers. Fluxus artists have been producing not good art per se, but inventive gags, among which this one hundred square meters Flux-Labyrinth (1975-1976) was a notable one. This was a collective efforts by Fluxus artists including George Maciunas, Larry Miller, Ay-O, Joe Jones, Bob Watts, Ben Vautier, George Brecht, Geoff Hendricks and many others. This project not only marked the particular organizational and collaborative genius of George Maciunas, but also perfectly illustrated his interpretation of Fluxus through a well-designed life-sized gag.

According to George Maciunas, the whole structure of gag is linear and monomorphic, just like Fluxus’ conceptual inventions. There are sight gags, sound gags, object gags, all kinds of gags. But no joke can be presented in multi-forms, nor can several jokes be made simultaneously, because people just cannot get it at once. Likewise, the Flux-Labyrinth is a cleverly designed and rigidly defined gag series, which unfolded linearly in the obstacle-laden one-way passage among extensive maze of puzzling.

In Maciunas’ letter to René Block, explaining the final plan of labyrinth with great detail, he wrote, “First door at entry is one with a small (about 10cm square) door with its own knob. One has to open it and find pass the hand through, looking for the knob of the big door on other side that will open door. This way only smart people will be able to enter. Anyone passing that door will be able to pass all obstacles. Idiot will be prevented from entering…”

The opening statement is clear, it is an intelligent game. As described by Larry Miller, “Part fun house and part game arcade, the labyrinth fits within Maciunas’ broader idea of Fluxus-Art-Amusement.” Fluxus, at least Mr. Fluxus, is a serious joker.” [credit]