[credit]

Cesar Chavez

“In the spring of 1966, a small group of California farmworkers and their supporters captured the attention of the nation.

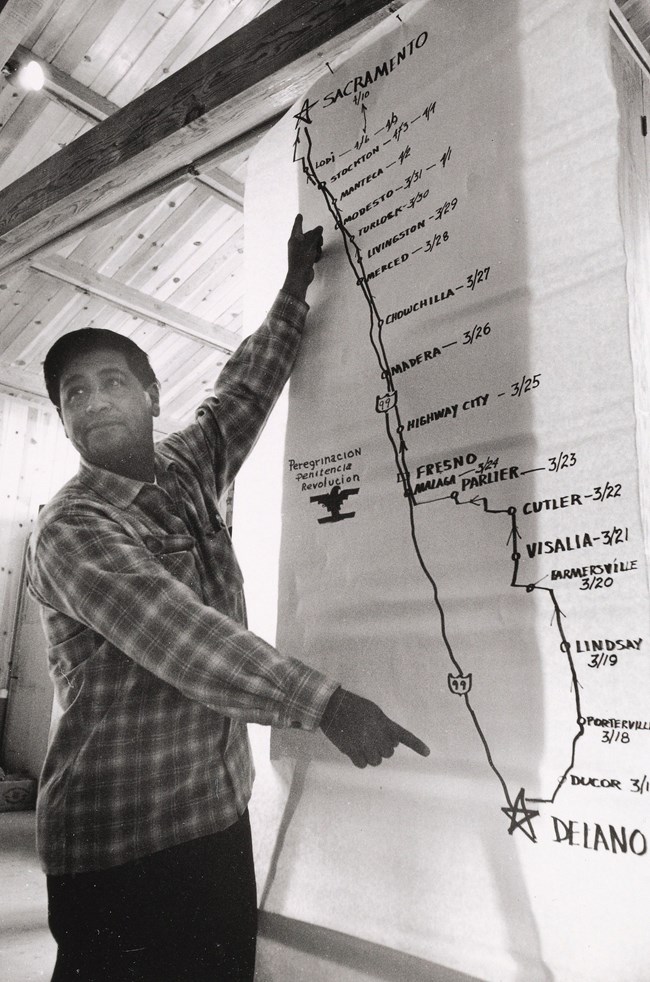

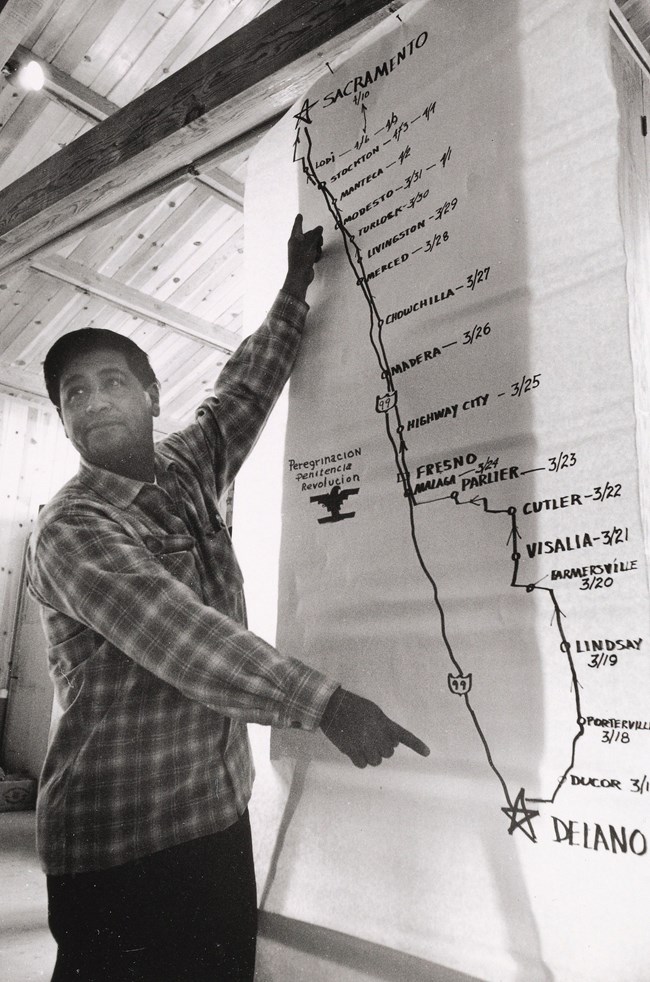

On the morning of March 17, 1966, nearly a hundred striking farmworkers, most of them Mexican American and Filipino, set out on foot from the small town of Delano, bound for the state capital in Sacramento 280 miles to the north. As they passed through the dusty highways and farming communities of the Central Valley, they were joined by student activists, union organizers, civil rights workers, and members of the clergy, all drawn to the remote regions of California in support of the farmworker struggle.

For six months, the farmworkers had been on strike. They refused to harvest grapes in the vineyards around Delano until the growers met their demands for higher pay, safer working conditions, and recognition of their unions, the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) and the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC).

But farmworkers were at a severe disadvantage in their efforts to negotiate the terms of their employment. They lacked the basic labor protections guaranteed to other American workers, including the right to union representation and equal treatment under the law. Whereas other workers could appeal to the federal government if their employers refused to bargain with their unions, farmworkers had no legal basis for making their demands. Instead, they took their pleas for justice directly to the American public.

From March 17 to April 10, 1966, the farmworkers and their growing number of supporters marched to shine a light on the conditions in the fields, exerting pressure on growers and government officials to finally take action. By the time the march concluded in Sacramento, the NFWA had won its first union contract, a landmark victory for the farmworkers and the beginning of what was not only a labor movement, but a cause—la causa—demanding for farmworkers the fundamental rights and freedoms to which other American workers were entitled.

The 1966 farmworker march was not only a part of the farmworkers’ struggle for justice; it was a key moment in the civil rights struggles of the 1960s. The farmworkers who marched from Delano to Sacramento represented the large, seasonal labor force, composed overwhelmingly of people of color, whose labor made California’s thriving agricultural industry possible. Although their labor produced fortunes from the soil, they were subjected to poor wages and working conditions. Farmworkers also experienced legal and illegal discrimination. In the farmworker movement, like the broader Civil Rights Movement, economic inequality and social injustice went hand in hand. By forging a unique coalition of labor, civil rights, and religious leaders, farmworkers successfully overcame the entrenched power structures of California agriculture. Their movement challenged some of the most powerful people and corporations in the state, demonstrating a remarkable resilience and ingenuity on the path from Delano to Sacramento.”