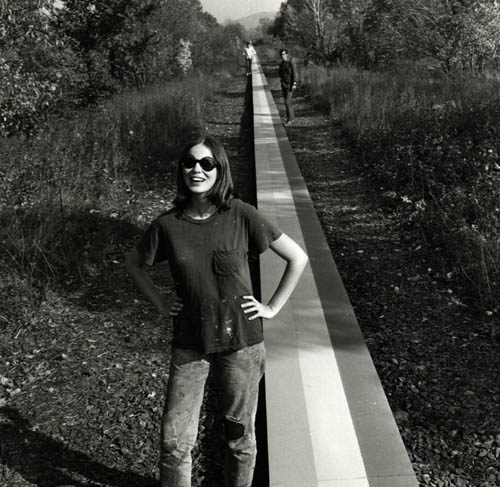

Sarah Rodigari is an artist whose practice addresses the social and political potential of art. Her work is site responsive, employing, durational live action, improvisation, and dialogical methodologies to produce text-based performance and installations.

Here, Sarah shares an update from Ravensthorpe.

I come from a big city and apparently live in the most densely populated suburb in Australia. I have spent most of my life in homes without a backyard. Modern living is accessible and convenient. There is a lot of choice – I wonder if because of this I spend a lot of time making unnecessary decisions, like which yoghurt to buy – everything is small, efficient, manageable and perhaps easily disposable. I don’t own a car, I walk everywhere. It has taken a while to slow down and let go of the accumulated habit of creating order and immediacy that I packed with me. I haven’t let go, or necessarily slowed down, I’ve just noticed that with distance, comes time. I think I’ve taken up more space, literally, hopefully not metaphorically.

The ute is the biggest vehicle I’ve ever driven, I was a little reticent to drive it at first, but now that I’ve been driving all over the shire meeting locals and conducting interviews about what makes an ideal word, I’m in love. I have learnt to 4WD which, city speaking, is just to say that I found a button to press. In a big car, under an endless sky on an open road. Like the generic protagonist in every Hollywood road movie, I get the feeling that out here there are no rules, everything is possible, and anything goes.

The utopia protagonist is no one, no gender, identity, history, ancestors, likes, dislikes,

They come from nowhere and bring nothing with them. (Bernadette Mayer, Utopia)

There’s nothing that can’t be done everyone’s giving it a go. If enough of you band together, you can make it happen, like the heavy haulage route, the herbarium and the swimming pool in Ravey or the community garden and the Mens Shed in Hopey.

When I ask about what might constitute an ideal world most people pragmatically suggest that they’re already here. I try to argue that utopia can’t exist in the present, it’s about striving for a future that we’re yet to realise – like a four-day work week or a universal minimum wage. This is hard to argue with people who have moved to a pretty and quiet beachside town on the edge of nowhere specifically to retire. This is the utopia they’ve been aiming for.

We agreed that isolation meant being far enough away for everything else to be conveniently accessible. But that didn’t mean not being globally connected. You can’t just ‘tune out’ to the weather, the coronavirus or the price of wool etc. It’s easy for me to arrive here with ecological assumptions about primary industry. Through my conversations, for many people farming and mining aren’t outrightly bad or wrong, the complexity of these industries and their relationship to land are lived with and negotiated daily. Does a simpler lifestyle allow more emotional and pragmatic space to address the ebb and flow of life, to embrace the paradox of a mine and farm next to a world heritage park and say, ‘yes and’?

As I step in closer to the community, simpler might mean less variety at the supermarket or choice on tinder but negotiating a co-existence with their environment and each other has a degree of attention and care creating a co-dependence that is very hard simply shut down.

This Must be the Place

It seems unusual to not want to be or strive for an ‘elsewhere’. Most of the people I have spoken to here in the Ravensthorpe shire consider here the place to be. I’ve been told on several occasions not to tell anyone just how great it is here: two small towns that are 200ks from the nearest service centre. Right next to a UNESCO listed national park with endemic flora and fauna which have survived an ice age. Numerous empty, pristine, soft powder sand beaches against multiple shades of blue ocean. Fish that that practically jump onto the jetty for you. People here live well into their 90s. The farmers have read Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu. There are multiple social clubs, a historical society and a community resource centre that is also a library, tourist office and eco shop. The staff know your name and calmly help with all your administrative, recreational or retirement needs. “Romance novels, it looks like you’ve already read them all, we’ll have to order some new ones in.”

It also has an aging population, with limited medical facilities. Education is also limited; most children have to leave at the end of primary school for secondary boarding schools. It is also prone to droughts, bushfires, flooding, shark sighting. Fruit and vegetables are relatively expensive and not super tasty (I hear cities are given priority when it comes to quality). The internet is patchy, put people seem to get on just fine without it. The limited water that is available is hard to drink.

On Friday February 14, at the Merlot club, the woman next to me asked if I’d like ice in my wine. “It’s rain-water ice” she said. I turned and asked why the water wasn’t from the tap she said, “no one drinks the water here, it’s terrible.” Colin to my left echoed “the water’s terrible”. It’s bore water and they’re scraping the bottom here. How can Utopia be a place with no water?

For nearly three years now. Ravensthope has carted its water from Hopetoun. BHP put in 42 bores and we’re now having to be careful which bores are mixed together to keep it below a salt level. We’re talking 40 years to refill, if we got normal rain and we’re not getting normal rains. (excerpt from Hearsay script)

With each new mine there is the potential for infrastructural support. When BHP came, they supported new bitumen roads, water bores, schools, police stations, local sport associations and business. They also built an entire new suburb and offered employment opportunities for some locals. (The government loves this, I guess it means there’s less for them to do). Alongside this local housing prices rose, some people sold, others could no longer afford to pay rent and left. Many, along with their new jobs took out mortgages, which, when the mine closed after seven months of operation, left them struggling to repay their loans and unable to sell.

FQM, the Nickle mine that is about to re-open, likes to employ locals, they don’t practice fly in fly out or drive in drive out. They encourage their employees to live in local towns and to get involved in the community as much as possible, they’re not BHP, they can’t afford to ‘throw money around, after all they’re a business. The price of Nickle is set to rise again due to the increase in manufacturing electric batteries for cars. They are bringing about 400 new staff to the area, that’s the same amount as the current population of Ravensthorpe.

There can be a divide between locals, farmers and miners. It’s not just that they keep different hours, one miner pointed out, small towns embrace the mines and the money but resent the influx in population and the change it can also bring to the quite nature of the town. Hopetoun was the most inclusive community she’d lived in so far.

Over the course of my residency I interviewed 20 people about isolation, belonging, home and utopia. Each interview lasted about two hours, some went for longer, working with five of these interviews I wrote a lyric poem and performed this back to the community over coffee, cake and sandwiches at the community resource centre. I have included and excerpt of the Hearsay script above.

On my last morning, I sit on the beach drinking coffee. I’m not ready to go back to the city.

I watch one of my favourite local dogs, a failed sheep-trial dog now much-loved domestic pet, herding waves. It’s little like striving for utopia. He’s making an excellent job of this impossible task. The poet Trisha Low suggests that to desire utopia is to desire emptiness: as a place, it is unattainable. Such a place is never truly possible to bring into being. Thomas More knew and suggested this when he coined the term back in 1516, it literally means no-place. Low suggests that maybe Utopia is not about striving for a future place but is about the impetus behind it “imaging life beyond what we know is possible… striving to create new ways to exist in the world in relation to one another” (Low 2019: 30).

Against the backdrop of what increasing feels like a global apocalypse, the shire is also on the precipice of social, ecological and economic change. It is by no means an ideal world, but I have experienced a care and intimacy amongst the community that hold moments of a utopian gaze that as left me longing for more.

-Sarah Rodigari” (credit)