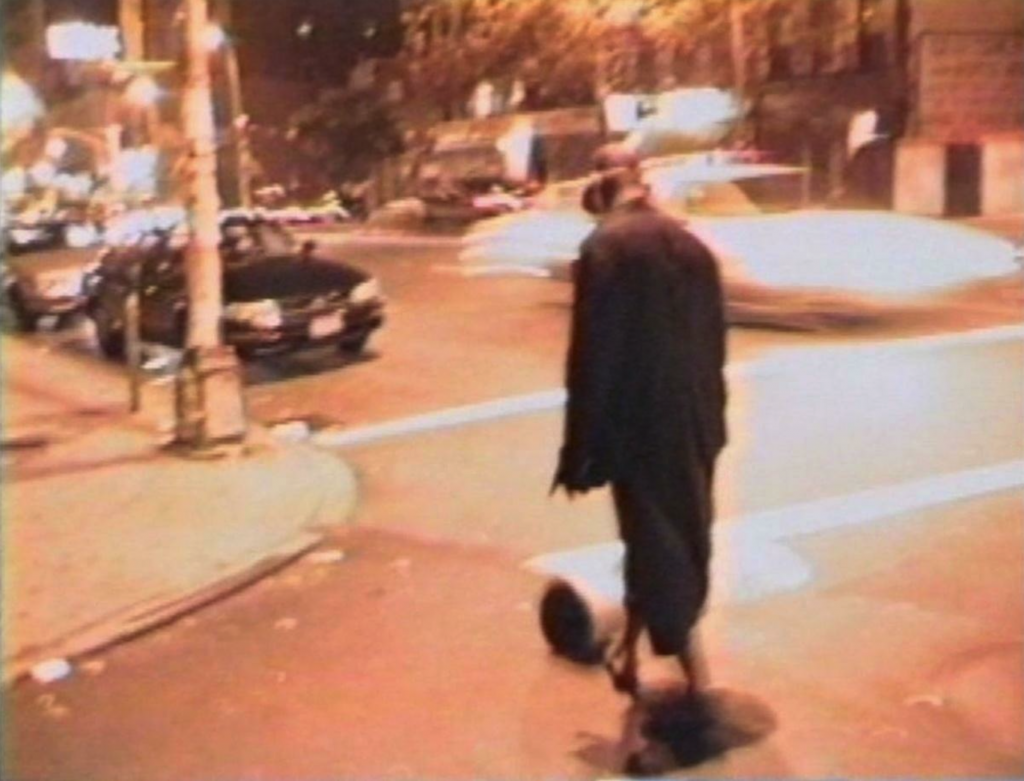

Wodiczko carried out a sequence of interviews with the New York’s homeless, learning about how they function by day and night in order to survive and protect their belongings. He was especially interested in those who collected glass, metal, and plastic for resale. Based on that, he designed the multi-functional Homeless Vehicle (1988-89) which reflected their real working and living conditions.

This vehicle is not a solution of the homeless crisis. It is an emergency tool for people who have no options, and an intellectual tool, as it articulates the complex situation of the homeless. It doesn’t represent them as garbage-collecting bums, but as people who use a device intended for specific purposes – which should not exist in a civilised world. This vehicle has a life-saving and didactic function, it finds a form for that which no one wants so know and see – the artist continues.

In this device, its user can wash, cook, rest, and sleep. He or she is able to safely store the collected bottles and cans. The inhabitant is also protected – the vehicle is visible enough to be safe from being smashed by, e.g. a reversing dustcart.

Such vehicle in the street provokes different questions. What is this part used for? How many of such vehicles are to be produced? Or: who are you? How did you become homeless? Then, that person is not only the demonstrator of the vehicle, but also a citizen of the city who has become homeless. That person works day and night, contributing to protecting the environment. He or she helps the city and should be paid for that – Wodiczko explains.