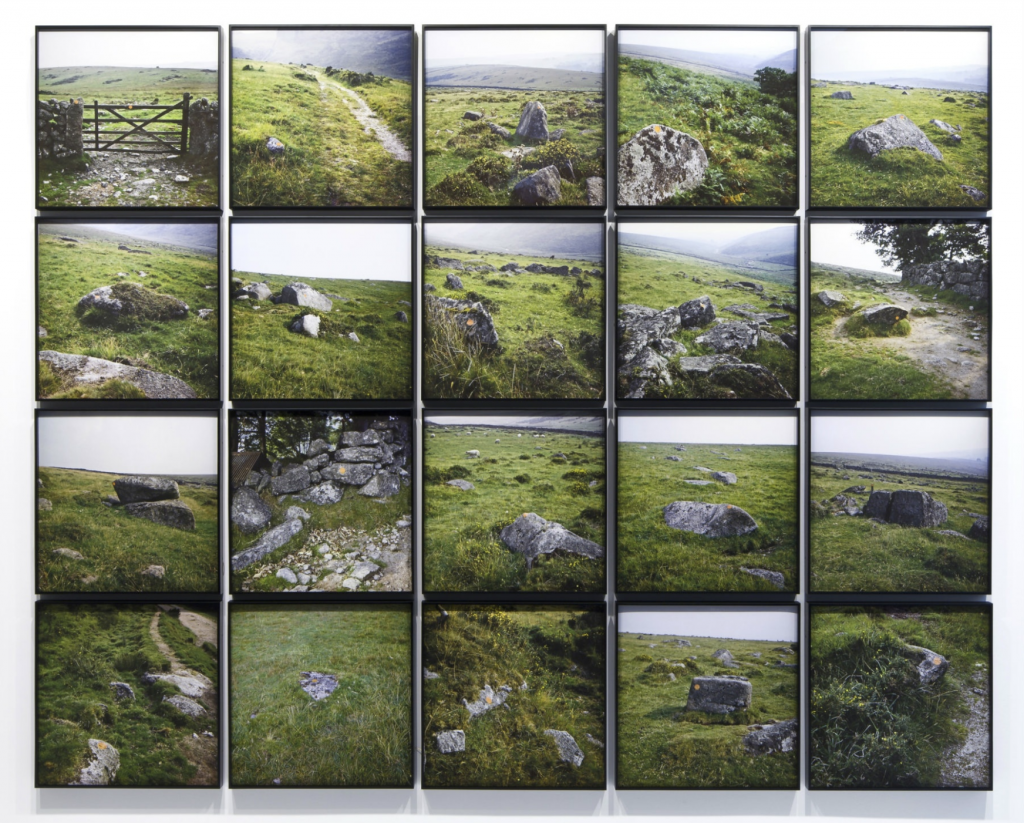

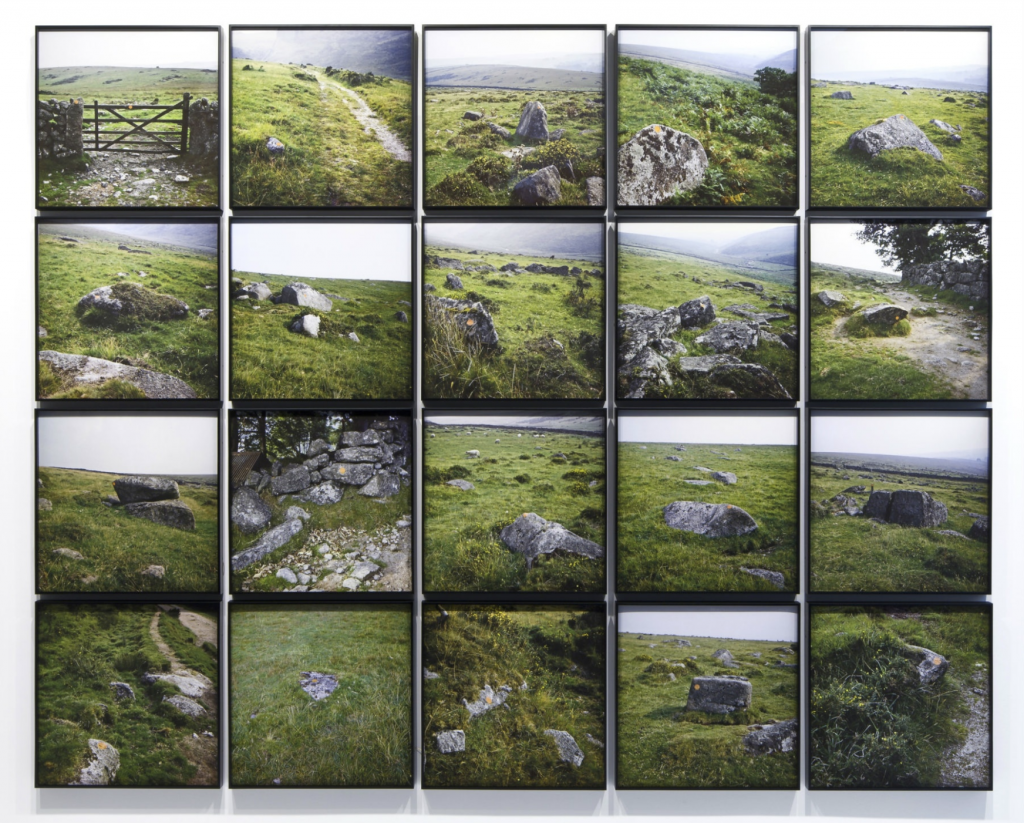

Trail Markers was photographed over a short stretch of publicly accessible footpath on the granite upland in the South-West of England known as Dartmoor. The path stretches between Two Bridges and Wistman’s Wood. The painted orange dots were a means to indicate the direction of the path for walkers and hikers. [Fig.1]

It was September 1969, and Holt and Robert Smithson were travelling through England and Wales in search of sites for sculptures—Smithson made several Mirror Displacement works during this trip. Their expedition was occasioned by Smithson’s inclusion in the London iteration of the international exhibition When Attitudes Become Form at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, which opened on August 27, 1969. They were also in search of some of the sources and inspirations of the picturesque (they had been reading William Gilpin’s writings, for example), and were curious about their own origins, as both had English ancestry. In the late eighteenth century Gilpin proposed ‘a new object of pursuit; that of examining the face of a country by the rules of picturesque beauty,’ which he elaborated in several volumes of his published Observations. These acted as guidebooks in Gilpin’s day, and Holt and Smithson retraced some of his footsteps.

Holt was the driver. The route to Two Bridges was challenging: narrow hilly lanes, in an unfamiliar land, driving on the ‘wrong’ side of the road. Then, less than a mile from the public highway, the signage of the path drew her attention to the rocky terrain. In a conversation with the author in September 2013, Holt said:

It’s very hypnotic these little orange dots, and was interesting because they were very cleverly placed. Every time you got to a place where you might wonder where the next step might be there would be this orange dot. It’s structurally interesting, and gave wonderful continuity to my slides. It was an artwork that evolved, came up, I didn’t know I was going to be seeing it and then was seeing it and thought this was perfect. It was a gift. It was already there. My job was to get the perfect photo.

Holt’s recollection casts the work as a kind of found sculpture or readymade.

Trail Markers was made in an era when walking had taken on new significance in art and culture. Artists such as Richard Long (b. 1945), a recent acquaintance with whom Holt and Smithson met up briefly on this trip, had made walking into art. And just a few weeks earlier a human walked for the first time on the rocky surface of an extra-terrestrial world in the first Apollo moon landing on July 20, 1969. On Dartmoor Holt encountered a place she found otherworldly but not entirely unfamiliar as it was somewhere she had visited imaginatively in stories from her childhood.

Most of the children’s books we grew up with were British. I would dream of little English towns and moors and wicked woods . . . The English landscape was already familiar, and yet the reality of experiencing those places had a visceral effect that has had a lasting effect on my work and thinking.

Holt’s progress slowed as she journeyed across the moor with Smithson. They moved from a car drive, to a walk, to stopping in Wistman’s Wood, where the ancient and contorted oaks seem the remnant of a primeval world. In the wood Holt took color images that became the photo work, Wistman’s Wood (1969). The images include close-ups of the twisted oak trees and the boulder-littered environment of the interior of the wood. She also made the first of her buried poems, Buried Poem #1 (for Robert Smithson). In this distinct body of work a poem was interred at a site that evoked a particular person to Holt, to whom she gave a booklet with detailed information about the site and how to find it. This first Buried Poem was more impromptu than the later ones, and intended to be private and personal. Holt and Smithson photographed each other here, as they did at other locations on their trip through England and Wales. They were developing a collaborative vision that would manifest in different forms in the work of each artist.

The twenty inkjet prints that now constitute the artwork Trail Markers were put together by Holt in 2012. [Fig. 1] Prompted by renewed interest in her work, a major monograph, and several solo exhibitions, this juncture marked a new urgency in Holt’s activity, in relation both to her own work and that of Smithson’s. Soon after she would edit her footage of The Making of Amarillo Ramp, and combine previously unseen slides of New Jersey taken by Smithson for an exhibition which opened shortly after Holt’s death in February 2014. Such returns, where “pieces of past and present mesh”, have repeatedly recurred in Holt’s life. They are arrested moments belatedly realized in another time, flashing up as they threaten to disappear irretrievably. When Trail Markers was printed in 2012 the distinctive square format of Holt’s 126 format slides seemed prescient of twenty-first-century images posted on social media. But in their deliberateness, these photographs differ radically from many of the images captured today.

Back then, you really studied what you were going to shoot, you looked at it very carefully, you tried framing it this way and that way, you worked it out, and then you shot it. That’s what was happening on that trip, with the orange dots.

Wistman’s Wood, the destination of the marked path, hardly features at all in the twenty photographs that make up Trail Markers, because the view back down to Two Bridges is the recurring one. The order of the images is not chronological, but directs a particular, deliberate, mode of attention. In the Smithson and Holt papers in the Archives of American Art there is a set of black and white photographic prints taken on the same path, most of which show views in the opposite direction towards Wistman’s Wood.[Figs. 2 and 4] Although either artist could have taken them, the fact that these photographs are identified in the archive in connection with his Mirror Displacement works suggests that they are by Smithson. Smithson does not appear to have made a Mirror Displacement in this location. Rather, a kind of mirroring happens between the two artists’ photographs and in the structure of the walk itself. [Figs. 2 and 3, and 4 and 5] It is as if they walked to the wood in black and white and back in color, with some kind of transformative experience happening in the wood itself. With Holt’s Trail Markers we retrace our steps: from ‘a weird place’ back to the car park.

It is forty years before the images re-emerge as Trail Markers. In these twenty images we see, on a stretch of English upland in 1969, a significant moment in the crystallization of a way of seeing the world.

About the Author

Joy Sleeman is Professor of Art History and Theory at the Slade School of Fine Art, UCL. She is a writer and curator whose research is focused on the histories of sculpture and landscape, especially 1960s and 1970s Land art. With Nicholas Alfrey and Ben Tufnell, she co-curated the exhibition Uncommon Ground: Land Art in Britain 1966-1979 (Arts Council Collection and Hayward Touring, London UK: 2013-14). Her publications include ‘Lawrence Alloway, Robert Smithson and Earthworks’, in L. Bradnock, C. J. Martin and R. Peabody (eds), Lawrence Alloway: Critic and Curator (Los Angeles US: Getty Publications, 2015) and Roelof Louw and British Sculpture since the 1960s (London UK: Ridinghouse, 2018).