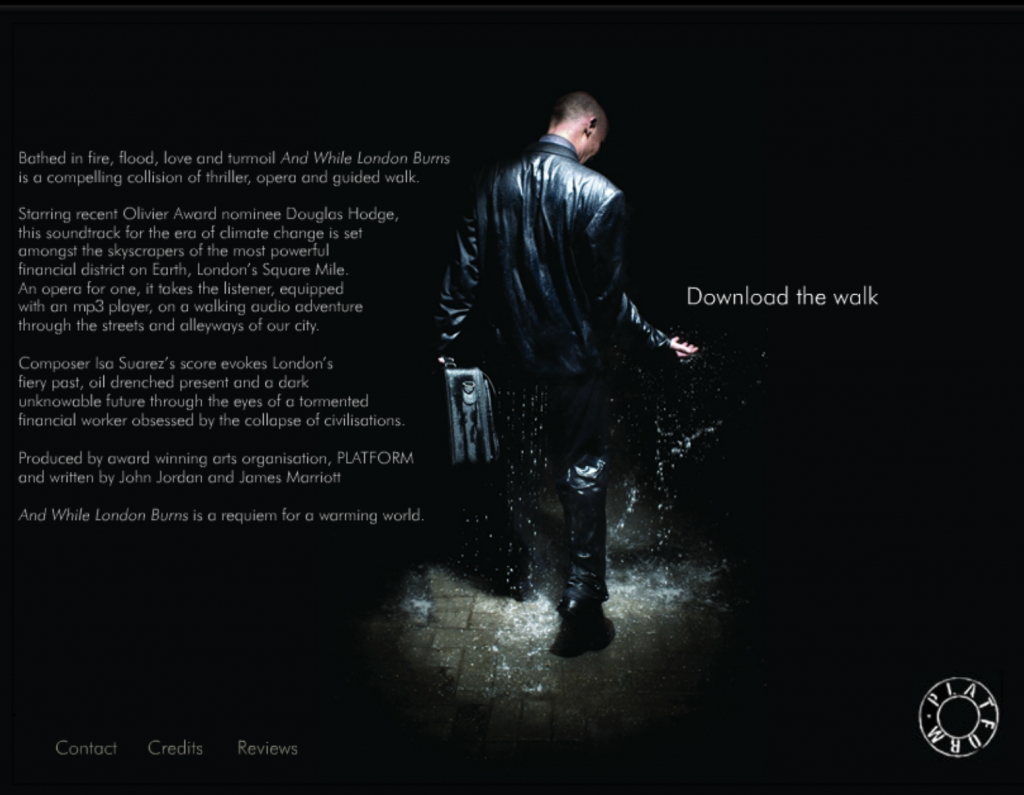

Screenshot of the main webpage for the opera

This is a downloadable opera/ walking tour for one; part fiction/ fact, it takes you through London’s financial district looking at impacts on climate change.

Screenshot of the main webpage for the opera

This is a downloadable opera/ walking tour for one; part fiction/ fact, it takes you through London’s financial district looking at impacts on climate change.

Wodiczko carried out a sequence of interviews with the New York’s homeless, learning about how they function by day and night in order to survive and protect their belongings. He was especially interested in those who collected glass, metal, and plastic for resale. Based on that, he designed the multi-functional Homeless Vehicle (1988-89) which reflected their real working and living conditions.

This vehicle is not a solution of the homeless crisis. It is an emergency tool for people who have no options, and an intellectual tool, as it articulates the complex situation of the homeless. It doesn’t represent them as garbage-collecting bums, but as people who use a device intended for specific purposes – which should not exist in a civilised world. This vehicle has a life-saving and didactic function, it finds a form for that which no one wants so know and see – the artist continues.

In this device, its user can wash, cook, rest, and sleep. He or she is able to safely store the collected bottles and cans. The inhabitant is also protected – the vehicle is visible enough to be safe from being smashed by, e.g. a reversing dustcart.

Such vehicle in the street provokes different questions. What is this part used for? How many of such vehicles are to be produced? Or: who are you? How did you become homeless? Then, that person is not only the demonstrator of the vehicle, but also a citizen of the city who has become homeless. That person works day and night, contributing to protecting the environment. He or she helps the city and should be paid for that – Wodiczko explains.

30 April 2011, 12.00 – 14.00

Turbine Hall, Tate Modern

Since the late 1960s British artist Hamish Fulton has made sculptures, actions, images and text pieces in response to his direct physical engagement with the landscape. In 1973 he resolved to ‘only make art resulting from the experience of individual walks’, a strategy that he maintains today.

Fulton will present Slowalk (In support of Ai Weiwei) at Tate Modern as a collective action created specifically in response to the iconic architecture of the Turbine Hall and in the context of the recent disappearance of Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, whose work Sunflower Seeds is currently on display in the east end of the Turbine Hall as the eleventh project in the series of Unilever Commissions. Fulton’s Slowalk (In support of Ai Weiwei) is conceived as a meditative experience to which he invites ordinary people to come together and walk very slowly, in a formation created by the artist over a period of two hours. This is a form of silent activism, where the participants are both art and viewer on a communal journey. Both Fulton and Ai Weiwei explore the role of political and social activism as a force for change in art and as such this action forms a public gesture of solidarity towards Ai Weiwei as a gesture towards freedom of expression.

Example of a slow walk:

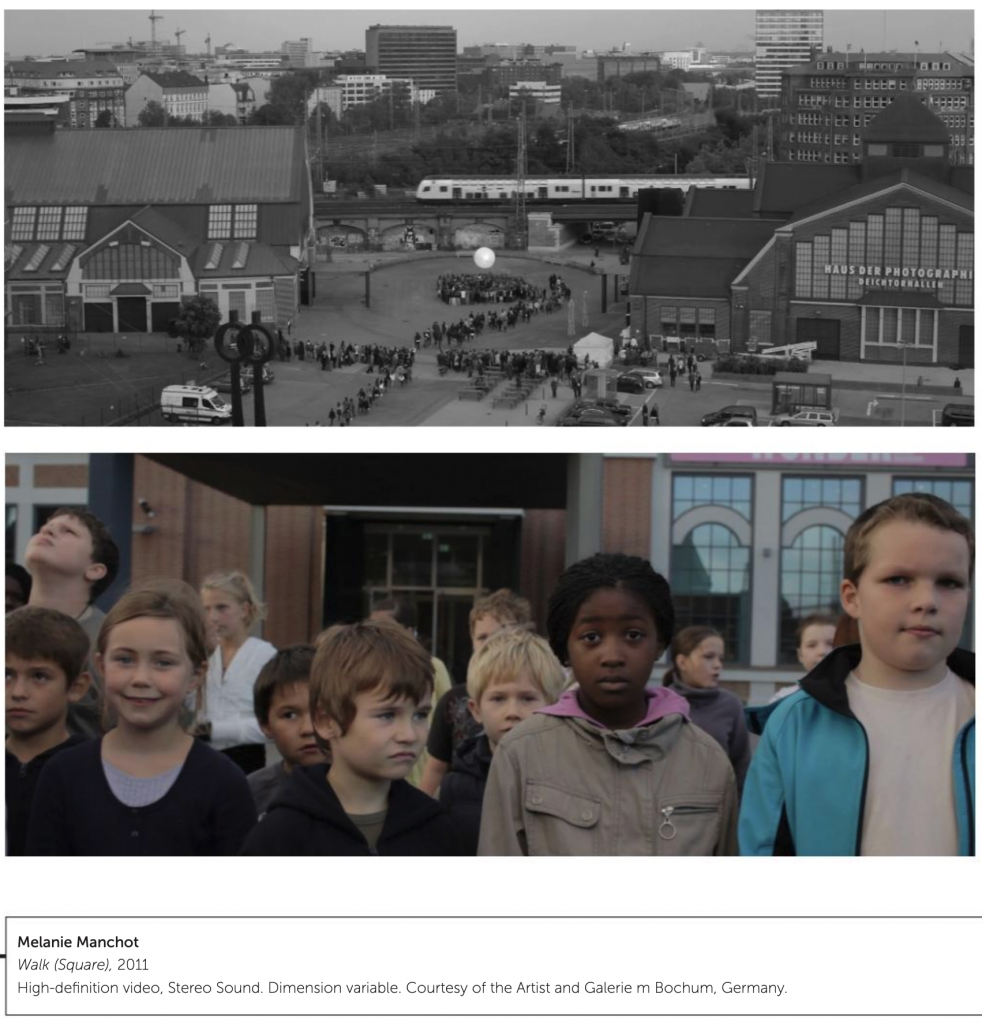

Walk (Square), 2011, Single Screen, HD, 20′40″

Walk (Square) forms part of an ongoing series of projects investigating collective gestures or situations enacted in public such as walking, dancing or celebrating. The work extends a practice based on an analysis of the construction of individual and collective identities and their performative representation through photography and moving image. Walking en masse—whether it be in processions, pilgrimages, in carnival or protest marches—forms the starting point for this video work made with 1000 Hamburg kids. Drawn into the centre of the city from all directions, with art as the ‘Pied Piper’, the work refers to current socio-political situations of protest as well as to recent research across different disciplines into the meanings of groups and crowds. The piece questions whether the act of walking may constitute a ‘form of speech’. On the square in front of Hamburg’s contemporary art museum a crowd of kids performs a simple walking choreography, based on Bruce Nauman’s video Walking in an Exaggerated Manner around the Perimeter of a Square, 1967– 1968, creating a shimmering form of movement that briefly produces a moment of collectivity and visual coherence before breaking apart.

[credit]

“At first glance, Melanie Manchot’s work shows us what might be a demonstration, a procession or a parade in the centre of Hamburg. The differences between the three, though seldom observed, are crucial. T h e historian David Cannadine has observed that when the French “put their social structures on public display they have parades (which are intrinsically egalitarian), whereas the British have processions (which are innately hierarchical)”. Demonstrations can be either hierarchical or not but, unlike the other two categories, are impossible to fully impose order on.

In ‘Walk (Square)’, a thousand children flock into Hamburg’s central square – with “art as the ‘pied piper”‘, as she puts it. Once inside the square, the children undertake what Manchot calls a “simple walking choreography” based on the Bruce Nauman work ‘Walking in an Exaggerated Manner Around the Perimeter of a Square’, seen elsewhere in this show. Manchot’s recreation of the earlier work in new form asks us to imagine how occupying public space has changed its meaning between ‘then’ and ‘now’. At the time of Nauman’s work, the purpose of protest was not in doubt, even if its efficacy was not universally accepted. Walking is, here, the means of occupying public space by traversing it. As Manchot puts it, “the act of walking constitutes a ‘form of speech'”. To walk – together – is in certain contexts a political act in the purest sense of the term. It is to ensure that one cannot be simply ‘walked over’ by those in positions of authority. To walk is to create “a moment of collectivity”, in the artist’s words.”

Dominique Blain “Missa” (1992)

100 pairs of army boots, mono-filament, metal grid, 700 x 700 cm

In the installation Missa, a hundred pairs of army boots suspended on nylon strings are arranged in a square grid. Raised slightly off the floor, the right-foot boots suggest the synchronised movement of military marching. The overall effect conjures up the destructive violence of political regimes that manipulate dehumanized troops like puppets. Although it was conceived in 1992, Missa continues to resonate wherever it is exhibited. This sensitive exploration of a military accessory, linked to individual soldiers but expressing a collective action, spans the history of wars and the atrocities they breed.

In her multidisciplinary practice, the Montréal artist Dominique Blain denounces the oppression that stems from relationships of power. She approaches historical references with restraint, using a few carefully chosen images and objects to arouse individual and collective memories. Leaving room for imagination, her socially engaged art gives viewers the leeway needed to reflect on the subject of war and totalitarianism. Blain’s work has been widely shown in Canada, the United States, Europe and Australia, notably at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art and in the 1992 Sydney Biennale. [credit]

A nearly deafening silence immediately strikes the viewer of Blain’s remarkably spartan installation. This soundlessness continues to resonate – and change – as one walks around her three-dimensional grid of strings and shoes, filling in its absences with haunting narratives and dark associations. Ominous connections between facelessness and force, blind obedience and inhuman strength, a sense of belonging and one of being utterly lost gain clarity as one contemplates her austere memorial to war and its – often abstract – if all-too-real consequences.

– David Pagel, Dominique Blain, Art Forum, 1993

Dominique Blain “Missa” (1992-2012)

Regina José Galindo, Quién puede borrar las huellas? (Who can erase the traces?, 2003), performance, Guatemala City, photo: José Osorio

In her most celebrated work, Who Can Erase the Traces? (¿Quién puede borrar las huellas?, 2003), she walked barefoot through the streets of Guatemala City, from the Palacio Nacional de la Cultura to the Corte de Constitucionalidad, carrying a basin filled with human blood into which she periodically dipped her feet. The trail of footprints visualized her reaction to the recent news that Efraín Ríos Montt, a former military dictator responsible for the most destructive period of the country’s internal conflict, had been permitted to run for president despite constitutional prohibitions. In this work, the line between Galindo’s body as object and subject was so subtle that the blood covering her feet appeared to be her own; she embodied the war’s victims, taking their blood as hers and appropriating their suffering.

The Green Line, Jerusalem, Israel, 2004; 17:41 min

In collaboration with Philippe Bellaiche, Rachel Leah Jones, and Julien Devaux.

Alÿs performed this walk by carrying a can of paint with a hole in it as he traced a portion of the “Green Line” that runs through the municipality of Jerusalem. There is a filmed documentary of the walk.

—

“In the summer of 1995 I performed a walk with a leaking can of blue paint in the city of São Paulo. The walk was then read as a poetic gesture of sorts. In June 2004, I re-enacted that same performance with a leaking can of green paint by tracing a line following the portion of the ‘Green Line’ that runs through the municipality of Jerusalem. 58 liters of green paint were used to trace 24 km. Shortly after, a filmed documentation of the walk was presented to a number of people whom I invited to react spontaneously to the action and the circumstances within which it was performed.” (credit)

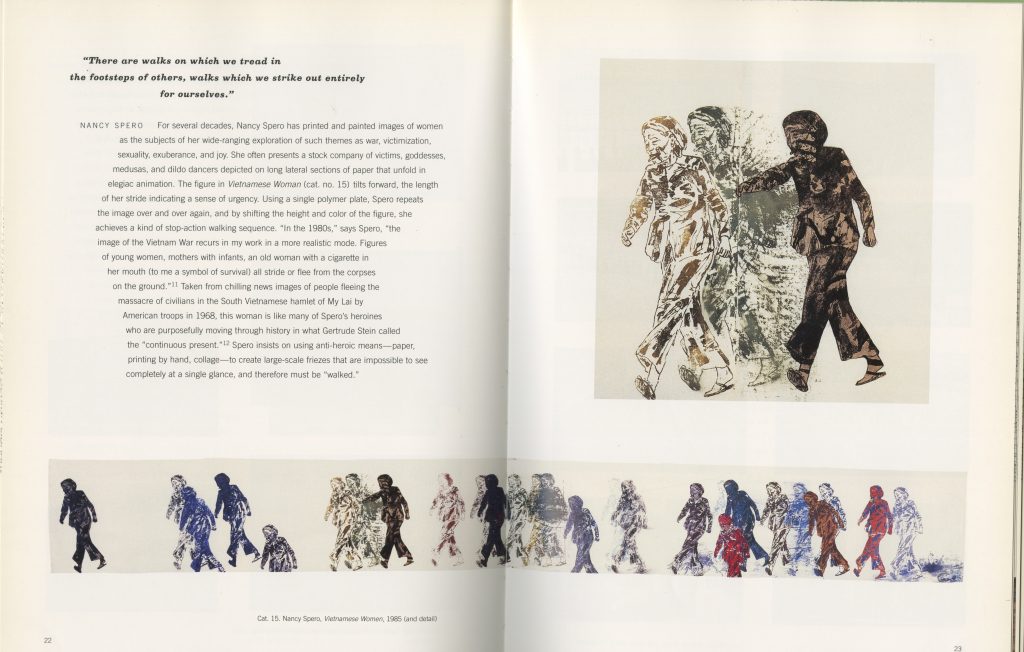

Nancy Spero

This is a large hand-printed and painted work that is so long it cannot be taken in without walking along it.

The subject matter is an image of a Vietnamese woman fleeing the massacre of civilians in 1968, taken from the news. Spero states the cigarette in the woman’s mouth is a symbol of survival.

(credit: Walk Ways catalog)

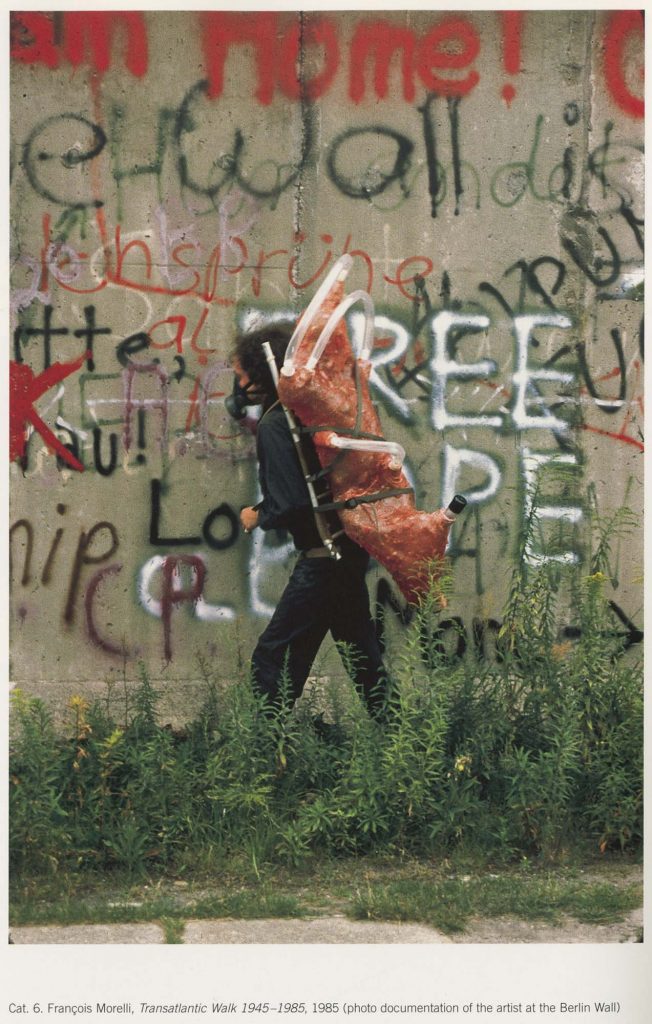

François Morelli

This walk commemorated the 40th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima. The artist carried a hollow fiberglass sculpture in the shape of a charred human torso on his back as he traveled from Berlin to Cologne to Amsterdam to Paris to New York to Philadelphi.

He archived the walk with photos, drawings, and writing. He engaged in many conversations.

He ritualistically filled the sculpture with water or air at various times symbolizing keeping his companion alive.

The first Pride march for gay rights was held in New York City on June 28, 1970. The event — officially known as the Christopher Street Liberation Day March — was spearheaded by a group of activists that included Craig Rodwell, Fred Sargeant, Ellen Broidy, Linda Rhodes and Brenda Howard, for the first anniversary of the Stonewall uprising.

The march’s route covered about 50 blocks and drew just a few thousand participants. Though the numbers were small, marches in New York, Chicago, San Francisco and Los Angeles that year eventually led to hundreds of Pride parades.

This was an important move towards civil rights, or guarantees of equal social opportunities and protection under the law, regardless of race, religion, sexual identity, or other characteristics.

Read the full article: How the Pride March Made History – The New York Times