[I had a vision] of this woman, another student. She was very tall and had a beautiful way of walking. I saw her in my mind’s eye, walking with this tall, white stick on her head which accentuated her graceful walk. I was very shy, but I started talking to her and proposed that I measure her to build this body-construction that she would have to wear naked and that would terminate in a large unicorn horn on her head. To my surprise she agreed … I invited some people and we went out to this forest at four AM. She walked all day through the fields … she was like an apparition.

(Quoted in Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum 1993, p.16.)

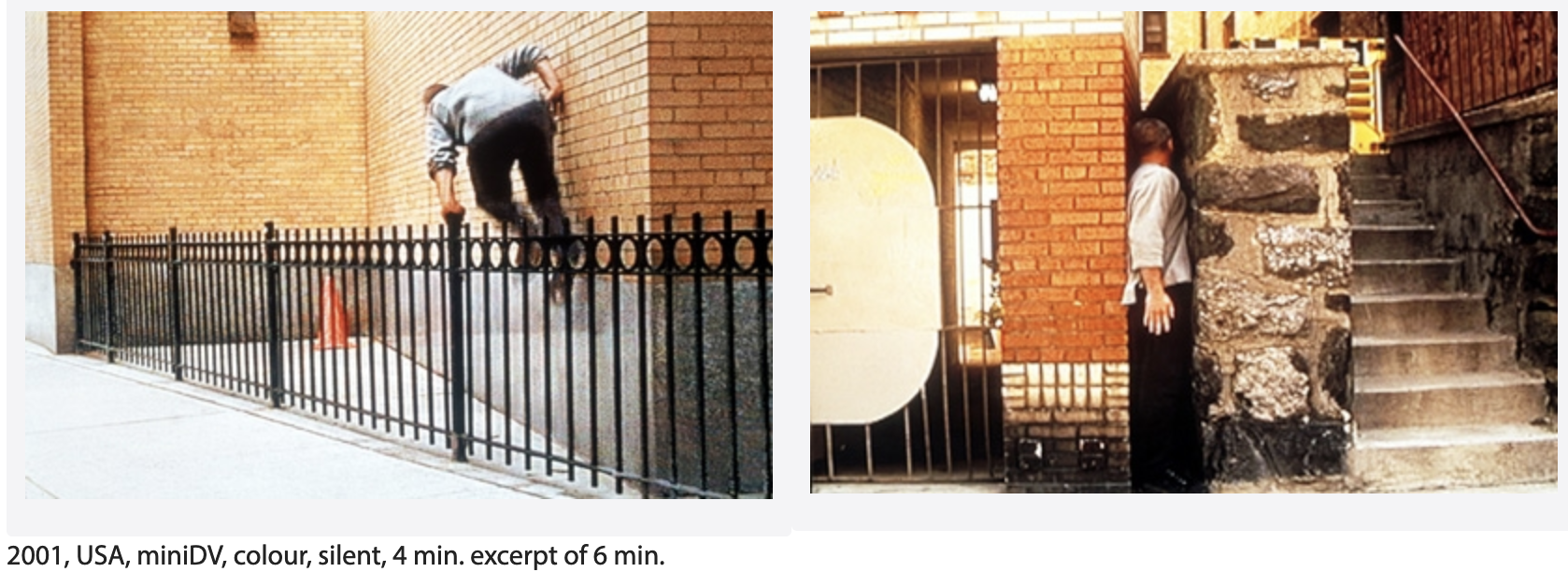

Developed from a 1968–9 preparatory sketch (Tate T12783), Unicorn is part of a series of body extensions – including Trunk 1967–9 (Tate T07855), Arm Extensions 1968 (Tate T07857), and Scratching Both Walls at Once 1974–5 (Tate T07846) – in which unwieldy prosthetics are used to emphasise the fragility and vulnerability of the human body. For Unicorn, however, the layers of meaning are more complex: the single woman clad in white, the original forest location and the symbolism of the unicorn reflect what curator Germano Celant has identified as Horn’s ‘intentional manifestation of white magic, in which woman tries to win out over reality and society’ (quoted in Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum 1993, p.44).

Emerging onto the art scene in the late 1960s, the German artist Rebecca Horn was part of a generation of artists whose work challenged the institutions, forces and structures that governed not only the art world but society at large. In art, this meant a renewed critical focus on the human body, contesting the commodification of art objects by foregrounding the individual. This focus on the human body took on a particular personal resonance for Horn, who was confined to hospitals and sanatoria for much of her early twenties after suffering from severe lung poisoning while working unprotected with polyester and fibreglass at Hamburg’s Academy of the Arts.

Horn has made work in a variety of media throughout her career, from drawing to installation, writing to filmmaking. Yet it is with her sculptural constructions for the body that she has undertaken the most systematic investigation of individual subjectivity. Her bodily extensions, for example, draw attention to the human need for interaction and control while also pointing to the futility of ambitions to overcome natural limitations. Similarly, her constructions, despite their medical imagery, are deliberately clumsy and functionless, while other works attest to the unacknowledged affinities between humans, animals and machines.

Further reading

Ida Gianelli (ed.), Rebecca Horn: Diving through Buster’s Bedroom, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles 1990, pp.38–9.

Germano Celant, Nancy Spector, Giuliana Bruno and others, Rebecca Horn, exhibition catalogue, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 1993, no.4.

Armin Zweite, Katharina Schmidt, Doris von Drathen and others, Rebecca Horn: Drawings, Sculptures, Installations, Films 1964–2006, Ostfildern 2006, pl.25.

Lucy Watling, August 2012″

[credit]