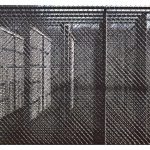

Chain Link Maze, 1978-79 (destroyed), Galvanized chain link fencing, 8′ x 61′ x 61′, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

—

“Adjacent to the University of Massachusetts football stadium in Amherst stands an 8-foot-tall chain-link fence encompassing an area some 60 feet square [by Richard Fleischner (1944-)]. …

The work sits, as do most of Fleischner’s projects, delicately on its terrain—it does not so much structure the natural, open site as it asserts itself discreetly, sensitively on the slightly rolling topography as a neat, geometrically concise object. Once through the corner entryway, we are confronted with a long corridor, the beginning of a path that winds, multicursal, toward a central inner chamber. Decisions must be made, and confusion is possible as we look through the wire grid at spaces beyond our reach. Both entry and path are ample, affording no sense of claustrophobia. One is struck instead by the open, hospitable feeling of the first corridors as they trace the perimeter. Comfortable strides are possible within the labyrinth; one can even turn or stop easily. It is not long before one of several decision points is reached—several paths can be taken but no great mistake can be made. It is as if the artist wants to coax us gently through this experience. There is no threat here but instead a fuller, more rewarding task of finding one’s own way. We are separated spatially but never visually from the outdoor environment as we can almost always see shimmering details through the various layers of mesh.

As one traverses the walkway, patterns of light reflect off the metallic walls, sometimes creating moiré-like surfaces, at others seeming almost flat and mat-colored. Fleischner has given us a visual labyrinth as well as a participatory maze. In no other maze are almost all the parts visible even as we are confined to a specific track. Depending on how many layers of chain link we gaze through (and this can vary from one to almost a dozen), details of the environment and other figures in the maze fade in and out of our sight. This seems then the perfect visual accompaniment to the fugitive spatial experiences we all undergo within a labyrinth.

In Chain Link Maze, Fleischner uses intuition to achieve his means—physical, optical and psychological experiences that depend on carefully measured spaces. In a broader context, a work like this directly engages some of the notions, particularly American, of the unbounded, natural environment. Fleischner works directly in the landscape, sometimes using concepts from rarified historical traditions. He has reasserted his ability visually to grasp the given landscape in a particularly American fashion, while simultaneously structuring situations within that landscape derived from conventions of garden design, architectural history and spatial perception. —Ronald J. Onorato ” [credit]

WikiMiniAtlas

WikiMiniAtlas