Alan Michelson (1953-, Mohawk) created a type of sculptural reenactment when he installed Earth’s Eye (1990) in lower Manhattan’s Collect Pond Park, outlining the now absent pond, a freshwater source that sustained Manhattan residents until tanneries polluted it and it had to be filled in during 1803. Forty cast concrete markers (22”x14”x6” each) referenced the natural and social history of the pond with low-relief imagery of plants and animals, and were arranged in the outline of the pond. Passersby walked around and within the installation, “bringing previous states of the locale into the here and now.” (Everett, Deborah. “Alan Michelson,” Sculpture, May 2007, Vol. 26 No. 4. Page 31.)

Category Archives: Education or pedagogy

Michael Belmore, Coalescence (2017)

“Michael Belmore’s Coalescence was conceived as a single sculpture in four parts, [as part of LandMarks2017/ Repères2017 invites people to creatively explore and deepen their connection to the land through a series of contemporary art projects in and around Canada’s National Parks and Historic Sites from June 10-25, 2017.]. Sixteen stones, ranging in weight from 300 to 1,200 pounds, are fitted together and inlaid with copper, then situated to frame the vast distance between the southernmost boundary of the Laurentide Ice Sheet near Grasslands National Park in Saskatchewan, to one of its points of drainage into Hudson Bay in Churchill, Manitoba.

Sites in Riding Mountain National Park and The Forks National Historic Site, both in Manitoba, punctuate the stones’ migration. Together, the four locations mark meeting points between water and land: ancient shorelines, trade routes and meeting places, sites of annual mass migrations of animals, as well as the forced displacement of peoples.

Belmore uses copper as a way to invest the stones with labour and value. The stones come against each other to create a perfect fit, while their concave surfaces move apart slightly to reveal the warm glow of copper to reflect light. Each crevice is filled with a fire that will be extinguished with age, turning brown, then black, and reaching a luminous green hue as it settles into the landscape. They are a marker of how everything comes from the ground and returns to it, and how these processes stretch far beyond human understanding of time.

Belmore has created a moment of connection between deep geological time of stone and the linear human time of labour. On the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Confederation, this connection acts as a reminder of how the timelines of national celebration do not take into account the timelines of the land on which they take place. The stones were going to traverse a land familiar with rising and falling waters to reach their locations, but spring 2017 brought a record snowstorm and a spring melt that washed out the rail line that serves as the main transport artery between Churchill and southern Manitoba.

The political negotiations that followed have left the responsibility for its repair unresolved — part of the continued legacy of colonialism, the challenges of northern transportation and migration, and the importance of international trade routes that go back to Canada’s first trading posts. Belmore’s piece remains intact in Churchill, its splitting and migration halted by the processes that reach out from its conceptual core.” [credit]

Aristotle, The Peripatetic School (335 BCE)

“While Alexander [the Great] was conquering Asia, Aristotle, now 50 years old, was in Athens. Just outside the city boundary, he established his own school in a gymnasium known as the Lyceum. He built a substantial library and gathered around him a group of brilliant research students, called “peripatetics” from the name of the cloister (peripatos) in which they walked and held their discussions. The Lyceum was not a private club like the Academy; many of the lectures there were open to the general public and given free of charge.” [credit]

—

“The Peripatetic school was a school of philosophy in Ancient Greece. Its teachings derived from its founder, Aristotle (384–322 BCE), and peripatetic is an adjective ascribed to his followers.

The school dates from around 335 BC when Aristotle began teaching in the Lyceum. It was an informal institution whose members conducted philosophical and scientific inquiries. After the middle of the 3rd century BC, the school fell into a decline, and it was not until the Roman era that there was a revival. Later members of the school concentrated on preserving and commenting on Aristotle’s works rather than extending them; it died out in the 3rd century.

The study of Aristotle’s works by scholars who were called Peripatetics continued through Late Antiquity, the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the works of the Peripatetic school were lost to the Latin West, but they were preserved in Byzantium and also incorporated into early Islamic philosophy. Western Europe recovered Aristotelianism from Byzantium and from Islamic sources in the Middle Ages.

The term peripatetic is a transliteration of the ancient Greek word περιπατητικός (peripatētikós), which means “of walking” or “given to walking about”.[1] The Peripatetic school, founded by Aristotle,[2] was actually known simply as the Peripatos.[3] Aristotle’s school came to be so named because of the peripatoi (“walkways”, some covered or with colonnades) of the Lyceum where the members met.[4] The legend that the name came from Aristotle’s alleged habit of walking while lecturing may have started with Hermippus of Smyrna.[5]

Unlike Plato (428/7–348/7 BC), Aristotle (384–322 BC)[2] was not a citizen of Athens and so could not own property; he and his colleagues therefore used the grounds of the Lyceum as a gathering place, just as it had been used by earlier philosophers such as Socrates.[6] Aristotle and his colleagues first began to use the Lyceum in this way about 335 BC,[7] after which Aristotle left Plato’s Academy and Athens, and then returned to Athens from his travels about a dozen years later.[8] Because of the school’s association with the gymnasium, the school also came to be referred to simply as the Lyceum.[6] Some modern scholars argue that the school did not become formally institutionalized until Theophrastus took it over, at which time there was private property associated with the school.[9]

Originally at least, the Peripatetic gatherings were probably conducted less formally than the term “school” suggests: there was likely no set curriculum or requirements for students or even fees for membership.[10] Aristotle did teach and lecture there, but there was also philosophical and scientific research done in partnership with other members of the school.[11] It seems likely that many of the writings that have come down to us in Aristotle’s name were based on lectures he gave at the school.[12]” [credit]

David Taylor, Working the Line (2007)

“Beginning in 2007, started photographing along the U.S.-Mexico border between El Paso/Juarez and San Diego/Tijuana. My project is organized around an effort to document all of the monuments that mark the international boundary west of the Rio Grande. The rigorous undertaking to reach all of the 276 obelisks, most of which were installed between the years 1891 and 1895, has inevitably led to encounters with migrants, smugglers, the Border Patrol, minutemen and residents of the borderlands.

During the period of my work the United States Border Patrol has doubled in size and the federal government has constructed over 600 miles of pedestrian fencing and vehicle barrier. With apparatus that range from simple tire drags (that erase foot prints allowing fresh evidence of crossing to be more readily identified) to seismic sensors (that detect the passage of people on foot or in a vehicle) the border is under constant surveillance. To date the Border Patrol has attained “operational control” in many areas, however people and drugs continue to cross. Much of that traffic occurs in the most remote, rugged areas of the southwest deserts.

My travels along the border have been done both alone and in the company of agents. In total, the resulting pictures are intended to offer a view into locations and situations that we generally do not access and portray a highly complex physical, social and political topography during a period of dramatic change.” [credit]

Kate Green, Watershed Line (2021)

“WATERSHED LINE

From May to September 2021

Kate is Artist-in-Residence in the Elan Valley.

The 1892 Water Act allowed Birmingham Corporation to purchase the watershed of rivers Elan and Claerwen. These 70 square miles would provide water to fuel the city’s industrial growth.

The WATERSHED LINE, the perimeter of the land claimed, was, and still is, marked by concrete posts.

https://www.elanvalley.org.uk/about/elan-links

Today, 81% of the Elan Estate is an Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). Ironically, the economic value of its water has protected it from the use of pesticides and other chemicals, preserving habitats for now rare plants and animals. However, harnessing the natural cycle of these valleys was a feat of Victorian engineering that accelerated industrialization, contributing to the current global environmental crisis.

As a ‘post-industrial’ pilgrimage in a ‘wild’ landscape, my walk from POST TO POST is a conversation about the complexities of the human footprint.” [credit]

Mindy Goose, Art, Access and Urban Walking (2017)

Mindy Goose, Art, Access and Urban Walking (2017)

“On Saturday 7th October, I led a walk as part of the Love Arts Festival 2017 programme.

The ‘Art, Access and Urban Walking’ grew out of the walk I led as part of Jane’s Walk Leeds in May. The idea was to create conversation around accessibility in urban and green spaces, and document it in a creative way through photography, writing, sketching, or spoken word. There were so many snippets of conversation I wish I had recorded, about the spaces we occupy, how we neglect visiting areas outside our neighbourhood; and once we hit the shopping park, conversation moved towards accessibility in public spaces.” [credit]

Heath Bunting and Kayle Brandon, BorderXing (2002)

“BorderXing, a 2002 commission for the Tate Gallery in London, in which Mr. Bunting, 37, and Ms. Brandon, 28, documented illegal treks they made across European borders.

“I’ve always wanted to be nomadic — to beg, borrow, find things,” Mr. Bunting said. He travels light, often with no change of clothes and only a few basics: a penknife, a diary, a passport.

The BorderXing Web site, available for individual use by request (at irational.org/cgi-bin/border/clients/ deny.pl) offers pictures, suggested routes and tips for evading the authorities. A vacation slide show of the couple’s journey is on view at the New Museum, as well as online, without registration, at duo.irational.org/borderxing–slide–show.

Despite the political provocation involved, the project retains the aura of a pilgrimage — to be close to the land, to throw off the weight of nationality and statehood, simply to put one foot in front of the other and go.

… BorderXing is concerned with the physical, visceral aspects of travel…” [credit] [full article as PDF]

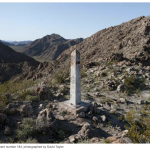

Dakota Commemorative Walk (2002-2012)

“They walked past red barns and white picket fences, past new housing developments and plowed fields dusted with snow. They walked with blisters on their feet and with hats pulled low to ward off the winter wind. They walked to remember.

The sixth annual Dakota Commemorative Walk ends Tuesday, Nov. 13, 2012 after six days retracing the footsteps of the 1,700 Dakota women and children who were forced to march 150 miles to Fort Snelling after the U.S. Dakota War of 1862.

Some call it Minnesota’s Trail of Tears.

“This is a ceremony,” said Gwen Westerman, who teaches humanities at Minnesota State Mankato and who has walked with the group since 2004. “It’s not a protest. It’s not a re-enactment. It’s a spiritual ceremony for healing and for honoring those women and children we descend from. We remember their strength and their determination.”

The first commemorative walk was organized in 2002, and organizers have held one every two years, leading up to this year, the 150th anniversary of the original march. After the Dakota War of 1862, the Dakota men who attacked government offices and white settlements were given cursory trials. Just more than 303 were condemned, and 38 were hanged in Mankato, remembered as a notorious event in Minnesota history.

After the war, 1,700 men, women, children, elders and mixed-race noncombatants were marched to a fenced camp along the river beneath Fort Snelling. During the winter of 1862-63 hundreds died of illness and exposure. In the spring, the remaining 1,300 were taken by steamboat and trains to a semiarid reservation at Crow Creek, S.D., where many more died of starvation and illness.

“They lived through three horrific experiences,” said Chris Mato Nunpa, a retired professor at Southwest Minnesota State University, who was bundled in a black coat and who talked as he walked along the shoulder of the road.

“They lived through this forced march, through the concentration camp, and through the forcible removal from Minnesota.”

He called their ordeal a genocide.

This year’s walkers set out just after dawn Wednesday from the parking lot of the Lower Sioux Agency in Morton, in the Minnesota River Valley. By Monday afternoon, the group had passed through the town of Jordan after covering about 20 miles a day. They walked on the shoulder of Scott County Hwy. 17, followed by a caravan of cars and vans carrying friends, supporters and elders too frail to make the journey on foot. Some people walk all six days; others join for a few days or even a few hours.

Each day, the procession is led by a woman carrying a sacred pipe wrapped in a blanket, surrounded by a quiet group. Farther back, people chat. The walkers stop and place a marker about every mile and honor two ancestors from the march.

At one stop Monday, a woman cleared weeds growing at the base of a tall electrical pole. She pounded a stake into the ground, topped with red and yellow ribbons. Someone called the names on the ribbon into the chilly wind: “Alek Graham. Maline Mumford.”

Then one by one, people went forward, took a pinch of tobacco from a leather pouch and sprinkled it over the stake.

“The name is not just a name. When we call their name, they come,” explained Nick Anderson, cultural chairperson for the Mendota Mdewakanton Dakota Community. “They are here with us.”

He said he walked as a way to thank his ancestors, one of whom was a sister of Chief Little Crow.

“When I think of what they had to endure, I don’t know if we can ever give enough thanks,” he said. “We survived, but we have lost a lot of our culture. Participating in this is a way for me to get some of that back.”

Other people came long distances to walk.

“The reason I’m here is because my great grandmother was on this march with her four kids and her mother,” said Reuben Kitto, who flew in for the march from Florida, where he spent 30 years working for Honeywell. Kitto spent his childhood on the Santee Sioux Reservation in Nebraska where many Minnesota Dakota were sent.

“This walk brings us back to the reality of how hard it was for them,” Kitto said. “The weather was a lot like this, there was a little bit of snow.”

“It’s a way for me to spend a day with my grandmother,” he said.

It’s also a way for him to spend time with his living family. His nephew Robert Thomas drove up from Winona to join the march for a day. Thomas is working on a commissioned play about the Dakota war and exile for the Minnesota History Theater and is concerned with helping both Dakota and non-Dakota remember the Dakota’s past.

“The old aunties and uncles are still passing down the stories,” he said. “The struggle is to get the younger generation interested.”

Kitto’s daughter, Ramona Kitto Stately of Shakopee, also was on the march, bundled in a long red coat and walking next to her father. Stately coordinates Indian education for the Osseo Area Schools and this year, as in past years, brought several students along on the walk.

As the sun started to dip low, she and others arrived at the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community center, where they would eat dinner together and reflect on that day’s walk.

“We carry a deep grief inside and if we don’t connect with that grief, we can’t heal,” Stately said.” [credit]

Yasmeen Sabri, Walk a Mile in her Veil (2016)

“Walk a Mile in her Veil is an introspection of Arab identity through the lens of the veil and its user, inviting visitors to try on the veil and understand first-hand the cultural, social, and feminist motives behind it.” [credit]

Norma Hunter, Walk this Way (2010)

Norma Hunter, Walk this Way (2010) [credit]